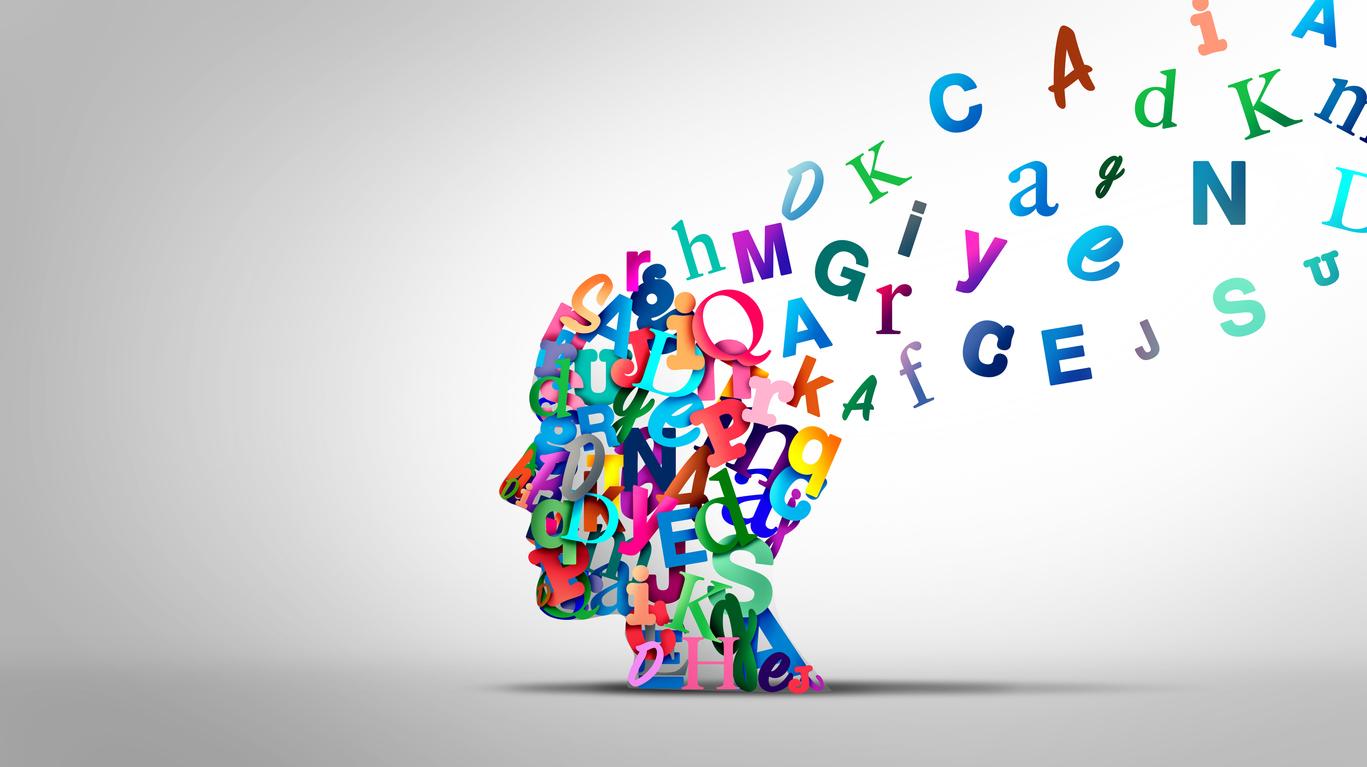

The more confident a person is in their judgments, the more they lack essential information to make them. Becoming aware of this cognitive bias opens a path to reducing conflict, according to a team of researchers.

- Study finds that confidence in our judgments increases when we lack critical information. This bias is called the “illusion of information adequacy”.

- An experiment shows that participants who received partial information on a problem were as sure of their decision as those who had all the data. This phenomenon is amplified by social networks, where hasty judgments are common.

- The solution? Adopt an open mind to fill in gaps and better understand opposing perspectives.

Know-it-alls know less than they think. A new American study, published in the journal PLOS ONEsuggests that the more confident we are in our judgments and opinions, during a debate for example, the more likely it is that we lack information essential to their formulation. This cognitive bias, called the “information sufficiency illusion” (illusion of information adequacy), explains in particular why conflicts of all kinds often tend to persist.

A deceptive confidence in our judgments

To arrive at this observation, researchers from Ohio State University conducted an experiment involving 1,261 American participants. They were presented with a hypothetical scenario: a school had to decide whether or not to merge with another school due to the depletion of a local groundwater system. The participants were divided into three groups: the first received complete information about the situation, while the other two only had access to partial arguments, either for or against the merger.

The results are surprising: those who received partial information were as confident in their decision, if not more, than those with all the data. “Those with only half the information were confident they had made the right decision, even without having the full picture”explain the researchers in a press release.

This illusion also manifests itself in our daily interactions. On social media, how many times have we seen users comment or share an article after only reading the title? This excessive confidence illustrates our propensity to believe that we have sufficient elements to formulate an opinion.

A perspective for reducing conflict

When participants who received partial information were exposed to opposing arguments, 55% maintained their initial position – a rate comparable to that of fully informed participants. The scientists point out, however, that this receptivity may not apply to deeper ideological issues, where people tend to reject or reconfigure new information to fit their beliefs.

This study offers a key to analyzing current, increasingly polarized debates, whether about vaccines, climate change or other sensitive subjects. Each side, convinced of its superiority, in fact operates with a limited point of view. “It’s as if two people are arguing about a painting, looking at it from different angles, each believing they see the whole picture”illustrate the authors of the study.

To combat this cognitive bias, they recommend a simple but powerful attitude: “The next time you disagree with someone, ask yourself: Is there something I’m missing to better understand their point of view?” This approach, listening to others, could reduce misunderstandings and open paths to reconciliation in our personal and social interactions.