More and more, the consumption of raw fish, squid and octopus is growing while Japanese sushi, Hawaiian poke and other Peruvian ceviches are reaching our tables. However, these dishes are not without risk since they can expose us to the various parasites carried by these animals when they are insufficiently cooked…

This problem is not to be taken lightly. Each year, nearly one in ten people are affected by “anisakiasis” after consuming such contaminated food. Specifically, the World Health Organization estimates that some 56 million cases of parasitic infections are associated with the consumption of fish products each year.

Today, anisakiasis is therefore an emerging global health problem. It is also an economic concern, due to the potential negative effects on consumer confidence and trade issues associated with infested fish products.

The worms that parasitize us

Among the parasites transmitted by fish, three large groups are capable of infecting us: flatworms, spiny-headed worms (acanthocephala) and roundworms (nematodes).

Infections with Opisthorchid, a family of flatworms, are the most commonly diagnosed, but it is found primarily in East and Southeast Asia. Its impact at the global level is therefore less than that of certain nematodes of the family of Anisakidae. The species of the genera Anisakis, Pseudoterranova And Contracaecum are thus at the heart of a large number of medical concerns.

In particular, anisakiasis (or anisakidosis), caused by larvae of nematodes belonging to the genus Anisakis, is considered the main threat to human health. Every year, on all continents, countless cases are described, which are linked in particular to the increase in the consumption of certain products such as sushi or sashimi.

In Japan alone, where it is traditional and common to eat these raw fish and seafood dishes, the average annual incidence of anisakiasis exceeds 7,000 clinical cases.

The long way from the worm to our stomach

How do you get anisakiasis? The answer lies in understanding the life cycle of the parasite.

Genre Anisakis includes nine species, three of which (A. simplex, A. pegrafii And A.physeteris) have been confirmed as zoonotic pathogens for humans. These nematodes parasitize a wide range of marine organisms and their life cycle includes dolphins, whales, seals and other mammals as final hosts, as well as fish and cephalopods (octopuses, etc.) in as intermediate hosts.

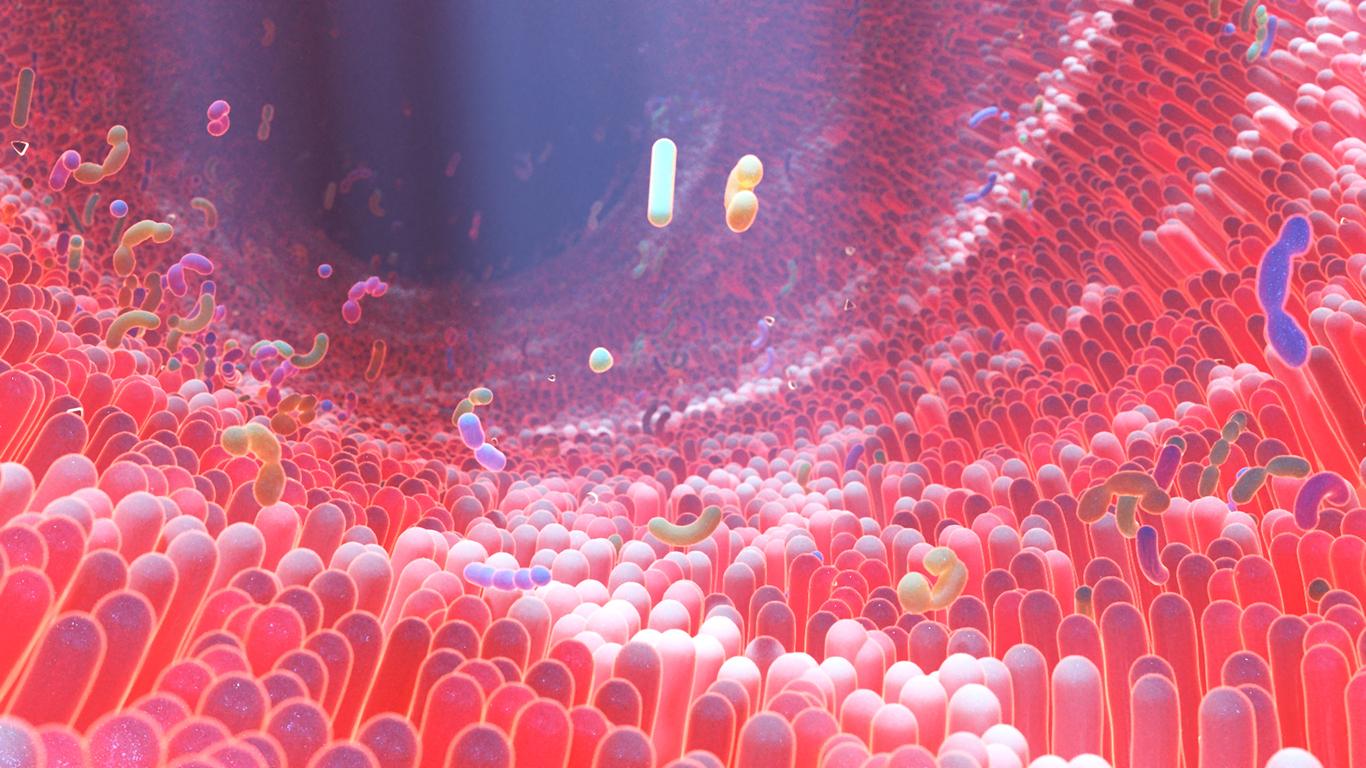

Adult worms are initially found in the stomach lining of marine mammals, where they reproduce. The parasite eggs are then expelled by the animal’s faeces and will develop in seawater. Now in the form of larvae, the nematodes will infect crustaceans (krill). When these crustaceans are the prey of fish or squid, the parasite (always in the form of a larva, but in the third stage) can reach the intestines of the predator and encyst on the surface of its organs, then in its musculature.

And that’s where we come in: we can become an accidental host of the parasite by eating cephalopods or raw or undercooked fish, or even smoked, salted or pickled, containing larvae ofAnisakis (of the third stage). Once ingested, these settle in our stomach and our small intestine.

Hives, stomach pain and vomiting

Once at home, the parasite is trapped… It can no longer reproduce, but can survive for a short time and cause anisakiasis. The disease, which varies from mild to severe depending on the person infected, can manifest itself in gastric, intestinal and abdominal disorders, allergic manifestations (fourteen allergens have been described) and even anaphylactic shock. The infection can settle outside the gastrointestinal tract, but this phenomenon is rare.

The most typical symptoms of gastric anisakiasis include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting within hours of ingesting the larvae. Involvement of the small intestine is less common, but when it occurs it can lead to massive inflammation and subacute symptoms, similar to those of Crohn’s disease, which develop one to two weeks later.

In addition, some workers in the fishing industry, cooks, and other professionals who regularly handle fish may suffer from occupational allergic anisakiasis. In this case, the ingestion of larvae or oral exposure to the parasite is not necessary for the disease to manifest itself: sensitization takes place via the proteins ofAnisakis that come into contact with their skin or respiratory tract.

The overall prognosis for anisakiasis is positive. Most infections are limited and resolve spontaneously after several weeks. Person-to-person transmission is not possible.

Ceviche, sashimi and marinated anchovies

Salmon, tuna, squid, cod, hake, mackerel, horse mackerel, blue whiting, sardines and anchovies are among the most frequently parasitized species.

More than 90% of anisakiasis cases worldwide are reported in Japan, and most of the remaining 10% in countries such as Spain, Italy, United States (Hawaii), Netherlands and Germany. These are areas where people traditionally eat raw or undercooked fish dishes, such as sushi and sashimi, ceviche and carpaccio, pickled or pickled anchovies, Hawaiian-style lomi-lomi salmon and salted herring. (In France, a study in 2016 estimated the number of cases at 10 per year on average (compared to 20 in Spain, etc. or a peak of 30 cases described in Italy in 2005), with ongoing development, particularly in terms of allergies. There is no epidemiological surveillance system yet, editor’s note).

How to get rid of the parasite?

Can we avoid contracting anisakiasis? Preventive measures are essential to control the disease, and some can minimize the problem. First, although the worms are resistant to pickling and smoking, cooking at temperatures above 63°C destroys the larvae. A temperature reached by frying, baking or grilling them.

Spain, which is among the most affected countries in Europe, its Food Safety and Nutrition Agency reports that traditional preparations of fish products (frying, baking, grilling) inactivate the parasite, as they allow reach a temperature of 60°C for at least one minute.

Semi-preserved (in airtight and pasteurized containers, salted, dried, etc.), as practiced on anchovies, cod, etc., involves processes that kill the parasite.

Another common solution is freezing, because the larvae are destroyed when they are subjected to a temperature of -20°C for seven days, or -35°C for more than 15 hours. If your refrigerator has less than 3 stars, on the other hand, it is prudent to buy frozen fish.

In some countries, to increase consumer food safety, commercially prepared sushi is even frozen before being offered for sale.

In addition, visual inspection of the liver, gonads and visceral cavity of gutted fish, as well as inspection of fish fillets, is preferable. European legislation requires that fish products showing visible parasites should not be offered for sale. It is advisable to buy clean and gutted fish.

Not all seafood is subject to the same restrictions. Oysters, mussels, clams, shellfish and other bivalve molluscs, as well as fish from inland waters (rivers, lakes, marshes, etc.) and freshwater fish farms, such as trout and carp, do not require freezing.

Similarly, fish from aquaculture may be exempted from the freezing requirement, provided that they have been bred from embryos obtained in captivity, that they have been fed with feed free of zoonotic parasites and that they have been maintained in an environment free of viable parasites.

This article was written by Raúl Rivas González, member of the Spanish Society of Microbiology, professor of microbiology at the University of Salmanca in Spain, and published on the website The Conversation.