Living with a donor heart

“I’m hot!” That was the first change Carla Joustra noticed when she woke up after her heart transplant. Used to always having icy cold hands and feet, this surprised her strangely. “I didn’t think my new heart would solve that problem.”

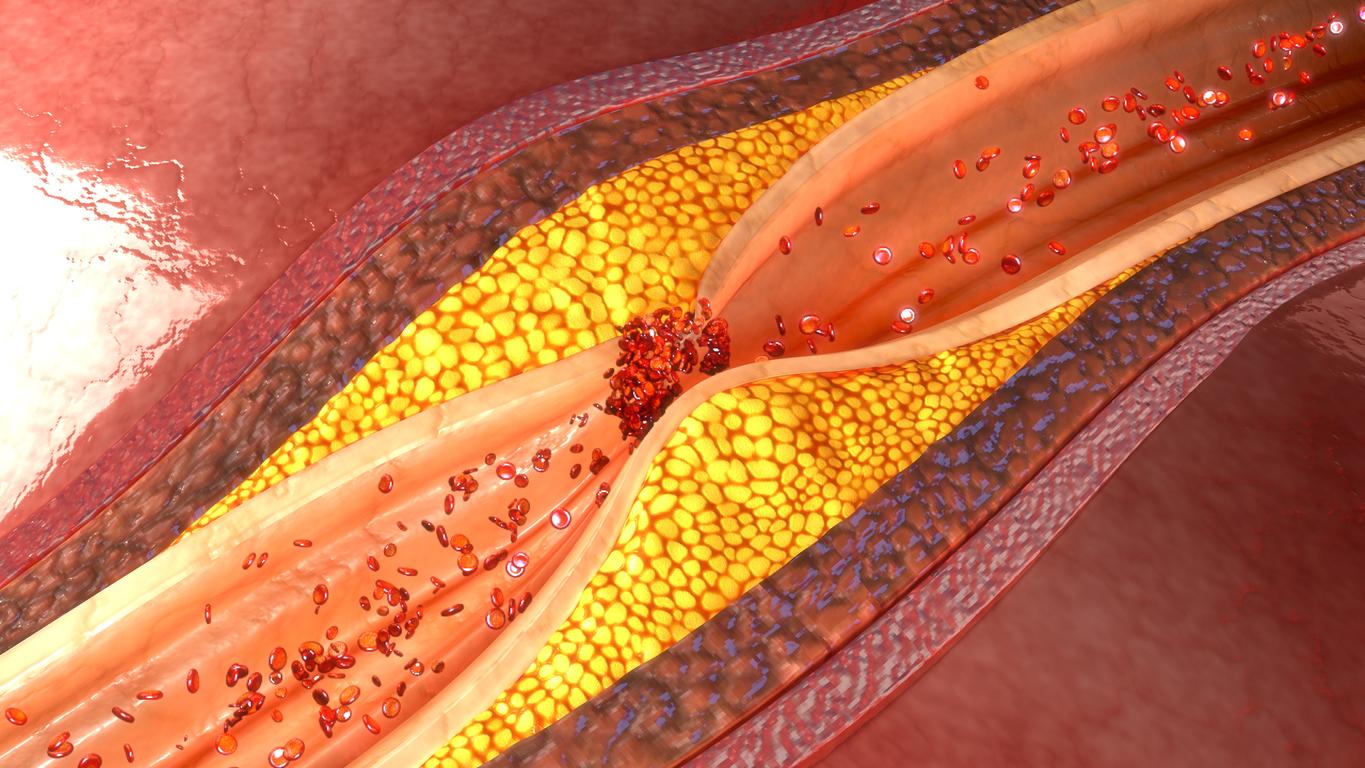

In 1994 she went to the hospital with a persistent cough and shortness of breath for lung X-rays. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, was the diagnosis, in other words: a heart muscle disease in which the heart muscle thickens and does its job less well. At first she was relieved that nothing was wrong with her lungs. She had no idea then how much the heart disease would turn her life upside down.

From 2000, her condition gradually deteriorated. In the end she could hardly do anything, she was so anxious. At the end of 2009 it was no longer possible – she was in hospital, out of hospital – and she was put on the transplant list. She tried to draw hope from the situation. After all, the place on that list meant that she had the prospect of a new life. But soon she deteriorated so much that there was only one goal: to get the transplant. One evening in May, the redeeming phone call came. The next morning she had a ‘new’ heart. Then another exciting period began.

Good prospects

“People often think that rejection is the biggest risk after a heart transplant,” says Joustra’s cardiologist, Johan Brügemann of the University Medical Center in Groningen. “But nowadays we can control that well with medication. The danger of infection is much greater. If you get through the first three months after a transplant without inflammation, the outlook is good.”

After a speedy recovery of three weeks in the hospital, Joustra went to a rehabilitation center. “There patients not only learn to rebuild their condition”, says Brügemann, “but also to deal with all the possibilities of their new life. Many patients have to get used to the fact that after all these years they can suddenly do everything again.”

Independence

The first period after the transplant was very emotional for Carla Joustra. “I could only cry,” she says. “All the tension and uncertainty of the previous years came out. I was so relieved!” After six weeks of rehabilitation, she was allowed to go home. Only then did she realize how small her world had become before the surgery. “For the first time in years, I was able to get on my bike in the morning to run an errand myself. My new heart has given me back my independence.”

Although she is still in the middle of the rehabilitation process, she already has plenty of plans for the future. “I want to travel and study art history. I’m not procrastinating anymore. In the past year I have met several heart patients who did not make it through their transplants. Because of my own experience and theirs, life will never come naturally to me again. I want to get everything out of it.”

heart transplant

Every year, approximately 30 to 35 Dutch people receive an ‘exchange heart’. The number of people on the waiting list for a heart transplant is increasing, from 44 in 2006 to 58 in 2009. This is because more and more heart patients survive longer due to better treatment methods, and because the number of (young) donor hearts that become available is decreasing as a result of the decrease in the number of fatal accidents in the Netherlands.

On average, patients are on the waiting list for a new heart for one to two years. Of the people who get a new heart, 90 percent are still alive after one year. After five years that percentage is 70 percent, after ten years 50 to 60 percent.

More information: Harten Twee (the interest group for people who have undergone or are eligible for a heart and/or lung transplant), T 030-656 96 36 or www.harten-twee.nl.

You can record in the Donor Register whether or not you will make your organs available for transplantation after your death: T 070-340 70 20 or www.donorregister.nl

Sources):

- Plus Magazine