On the occasion of Atrial Fibrillation Week 2022, we interviewed Professor Jean-Claude Deharo, cardiologist and rhythmologist, head of the cardiology department at the Timone hospital in Marseille, on the recurring question of maintaining treatment. anticoagulant during illness.

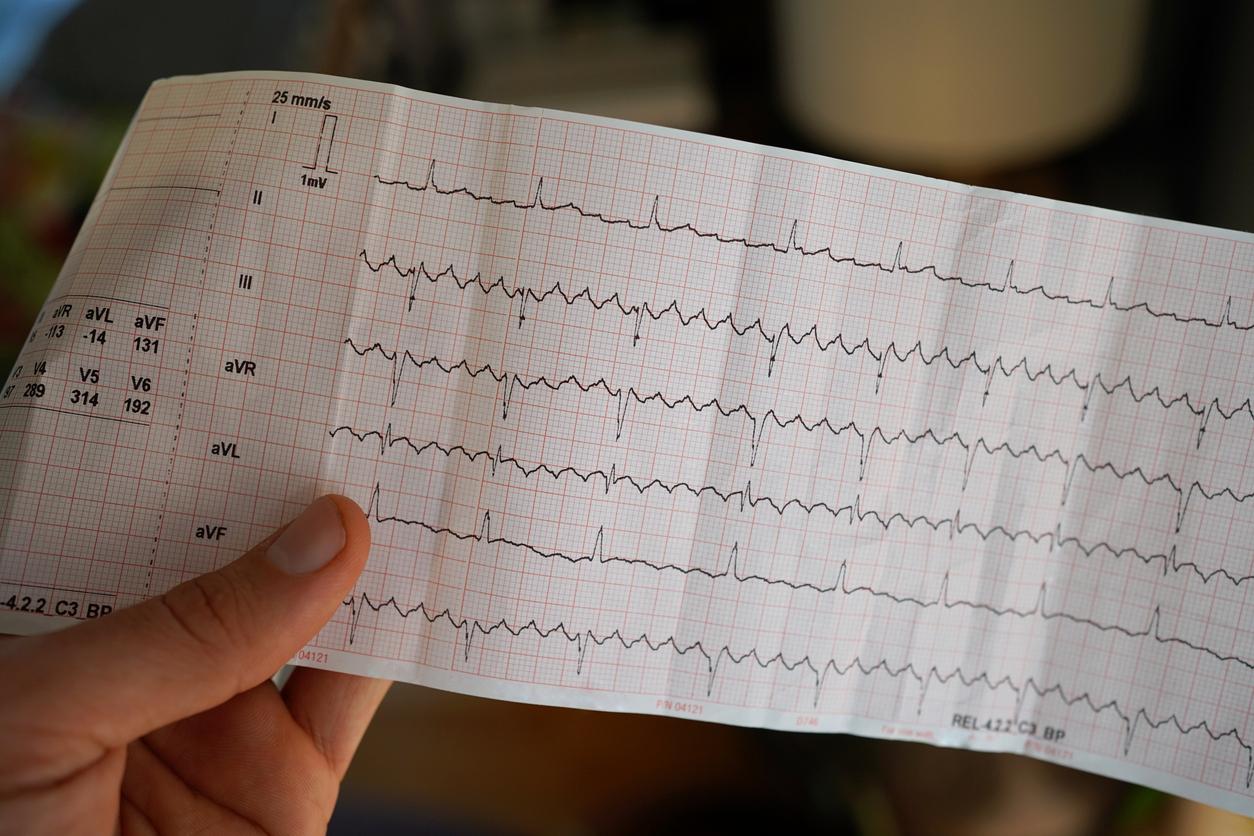

- Atrial (or atrial) fibrillation is a heart rhythm disorder that causes the heart to race and beat irregularly.

- The major risk for the patient is to have a stroke.

- When the patient meets the medical criteria, anticoagulant therapy reduces the risk.

“Atrial fibrillation (also called atrial fibrillation) is the most common heart rhythm disorder (so much so that doctors sometimes simply refer to arrhythmia as atrial fibrillation)“, explains the Vidal encyclopedia. In France, it is estimated that this disorder affects four people out of 1,000, or approximately 250,000 individuals. The incidence of this disease increasing with age, its prevalence is growing rapidly in France, linked to the aging of the population Its main complication is the embolism caused by stagnation of blood in the atria which can form clots which are then transported to the arteries… at the risk of clogging them, especially for the smallest present in the brain!So to reduce the risk of stroke, anticoagulant drugs can be prescribed to certain patients.Explanations with the cardiologist Pr Jean-Claude Deharo.

“Atrial fibrillation is ultimately a silent killer”

Anticoagulant treatment has made many advances in recent years. What is its real benefit-risk ratio over the long term in atrial fibrillation?

The risk of embolism during atrial fibrillation must be borne in mind. Atrial fibrillation is ultimately a silent killer. That is to say, we don’t really realize it. Moreover, the patients themselves do not always feel their atrial fibrillation, but the embolic risk is a certain risk. And we know that in the absence of heart disease, the embolic risk of atrial fibrillation is already four times higher than that of the general population. This can go up to 18 times when there is heart disease, in particular valvular, very embolic as mitral stenosis.

So I believe that this risk absolutely must not be minimized and, if in the end we have few certainties in medicine, there we still have some in the field of anticoagulation of atrial fibrillation! There have been very clear studies that have shown, but really with a concordance that leaves no room for doubt, that the benefit of anticoagulant treatment is enormous: the excess embolic risk is reduced by nearly 70%. This means that we can tell a patient that we are going to reduce him almost to the risk of stroke that he would have in the absence of atrial fibrillation.

There is therefore no doubt about the value of anticoagulation. The difficulty is rather to try to position this treatment between the certain benefit of which we have just spoken and the risks which exist but which are not as important as what one can think.

How do you know if the patient needs anticoagulant treatment?

Precisely, a certain number of situations plunge your colleagues into delicate dilemmas, in particular when there are patients at risk of falling, associated treatments or certain comorbidities. Are there situations of AF that do not justify anticoagulation? And what can we offer as an alternative solution?

So it may seem a bit binary as reasoning, but we use a score to know if a patient should be anticoagulated when there is atrial fibrillation, which we call the CHA2DS2-VASc score. It is a score of comorbidities associated with atrial fibrillation: heart failure, arterial hypertension, atheromatous disease, etc. We will also talk about history of stroke, the age of the patient which is a very important element in the embolic risk, and for example, sex. We know that the female sex is a little more exposed.

So it is this CHA2DS2-VASc score that guides us to know whether to anticoagulate an AF. And then it is correlated with other scores including that of the risk of bleeding, such as the HAS-BLED score for example. So that’s the difficulty! And finally the crest line on which we find ourselves when we want to anticoagulate a patient, when the CHA2DS2-VASc increases, that is to say when finally the risk of embolic accident and therefore the expected benefit of anticoagulant treatment increases, the HAS-BLED also increases in parallel. The fact remains that overall, the risk-benefit ratio of anticoagulant treatment can be relatively predicted by a certain number of clinical variables, and there are very few situations during which a patient will not have to be anticoagulated. These situations are completely exceptional.

I would also like to come back to a first thing that is important, which is that this CHA2DS2-VASc score, when it is zero, justifies not anticoagulating patients. And that is something that is important to remember because we sometimes see patients who receive anticoagulant treatment and do not really need it: but we can understand that it can reassure them. It can reassure a very anxious person who has read something in a very serious literature talking about the embolic risk of atrial fibrillation of taking anticoagulant treatment. But when we have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of zero, we know that the benefit of the treatment is almost nil, whereas the bleeding risk of the treatment does exist, and it will therefore exceed the benefit in this situation. The ratio is therefore not at all in favor of anticoagulant treatment.

From the moment we have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 in men or 2 in women, we begin to have a slight excess of benefit over risk. This is why the Europeans recommend anticoagulating these patients. The Americans leave room for a discussion there and think that it is not essential to do so. But on the other hand, from the moment the CHA2DS2-VASc score reaches 2 in men or 3 in women, then the indication for anticoagulation is absolute and this indication for anticoagulation should only be finally discussed in very special cases. Especially if a patient has had a bleed, with an organ specialist who tells us that the risk of new bleeding is extremely high and that there is a risk at that time, really, to continue on this path. But these are quite exceptional situations.

And so when there has been a recent cerebral bleed, or when there are indeed diseases, with or without a bleeding disorder, which risk exposing people to major bleeding, are there any means of preventing the risk of AF stroke without giving anticoagulants?

In very specific situations, I repeat myself a little, but these are situations in which an organ specialist, for example a neurologist, would tell us that there is a risk of new bleeding after a first bleeding or even bleeding before there was too much of it. Well, in these situations, we will sometimes observe a formal contraindication to anticoagulation. In these cases, there are alternatives. Today, they are not alternatives to anticoagulant treatments, they are only alternatives to be used when the treatment is contraindicated.

These are the left atrial occlusion systems. These are systems that are placed by catheter in interventional cardiology. A prosthesis that will occlude the left auricle which is known to be the site of clot formation in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. In most cases, this is a technique that is effective. Protection is probably less than that of anticoagulants. So, I repeat, this is not an alternative. It is only a technique which will make it possible to minimize the risk whereas the anticoagulant treatment is not usable.

“The embolic risk of atrial fibrillation is not related to the rhythmic status of the patient”

I would like to come back to a rather special situation, which is the situation of a patient who would have an indication for anticoagulant treatment and who, following a treatment, whether it is medicinal or whether it is a treatment by endocardial ablation, does not feels more atrial fibrillation and therefore feels completely cured. Well, this patient very often comes back to see us, to tell us: “Listen, what you did to me is perfect. I no longer feel fibrillation, but I felt it, I was really able to know at any time if I was in fibrillation or if I was in normal rhythm. So I would like us to stop this anticoagulant treatment”. Well there, I really warn against this reasoning, even if it is a little counter-intuitive. It is not because the patient no longer feels atrial fibrillation that the treatment should be stopped, for two reasons. The first is that it is not because he no longer feels fibrillation that he no longer has it. It is known that most episodes are completely asymptomatic. And the second is that the embolic risk of atrial fibrillation, as indicated by the CHA2DS2-VASc score, is not linked to the rhythmic status of the patient. It is linked to a whole bunch of other factors that are contained in the CHA2DS2-VASc, which have nothing to do with atrial fibrillation, and which are comorbidities, as we said. And these comorbidities, the patient has always heard them. Therefore, a successful ablation or a drug treatment that seems very effective does not justify interrupting the anticoagulant treatment if the patient has a CHA2DS2-VASc score that deserves to be maintained.

Another classic situation is that of maintenance of anticoagulation after an external electric shock which has reduced the atrial fibrillation. What to do with the anticoagulant treatment? Should we maintain it or not maintain it? Well, the answer is simple: an electric shock is four weeks of mandatory anticoagulation, the time for the auricle to resume a completely satisfactory contractile function. And then there will again be the question of the CHA2DS2-VASc score and whether or not to continue anticoagulant treatment depending on the score. So it’s a bit the same reasoning as after an ablation. Finally, we do not stop the anticoagulant treatment because we put the patient back in sinus rhythm but according to the comorbidities which testifies to the state of the left atrium.

Anticoagulants: “Under no circumstances should the patient’s age constitute a contraindication”

In the end, what is your message for your colleagues?

The main message that I would like to take away is that anticoagulant treatment has a good risk-benefit ratio when used correctly, and this must be explained to patients. Under no circumstances should the official age of the patient constitute a contraindication to initiating anticoagulant treatment. Under no circumstances should the fact of having had a treatment that appears to be very effective on atrial fibrillation allow the treatment to be stopped. I believe that we must always ask ourselves the question of the benefit of the treatment and clearly explain to the patients that, in most cases, the benefit greatly exceeds the risks. If they are very old subjects or subjects who would have a contraindication to anticoagulant treatments due to renal insufficiency, well then we will discuss. We may have other solutions to offer patients. But this is a situation which, in our practice, is still relatively rare. In most cases, patients can be treated with anticoagulants, provided that there is a little more monitoring, if there are factors which suggest that there is a risk of bleeding.