On the occasion of Pink October, Why Doctor was able to discuss with researcher Céline Vallot the scientific advances concerning the role of epigenetics in the progression of triple negative breast cancer.

Why Doctor: Céline Vallot, you are a CNRS research director, responsible for the Dynamics of Epigenetic Alterations in Cancer group. What do your days consist of?

Céline Vallot: I manage a team of around a dozen people at the Institut Curie. These are both people who analyze data (data scientists), and people who do experiments in the laboratory. I discuss with them their research project, the problems they encounter in their laboratory or in IT to try to resolve them. I also spend part of my time looking for funding, responding to calls for tenders… For example, I have just passed an oral exam to obtain an ERC grant. I also look at what is happening in other laboratories, I discuss with collaborators who have complementary technologies that could advance our research, etc. And finally, I set aside some time to do data analysis and research in the first sense of the word.

Triple negative: “it is very heterogeneous, hence the difficulty in treating it”

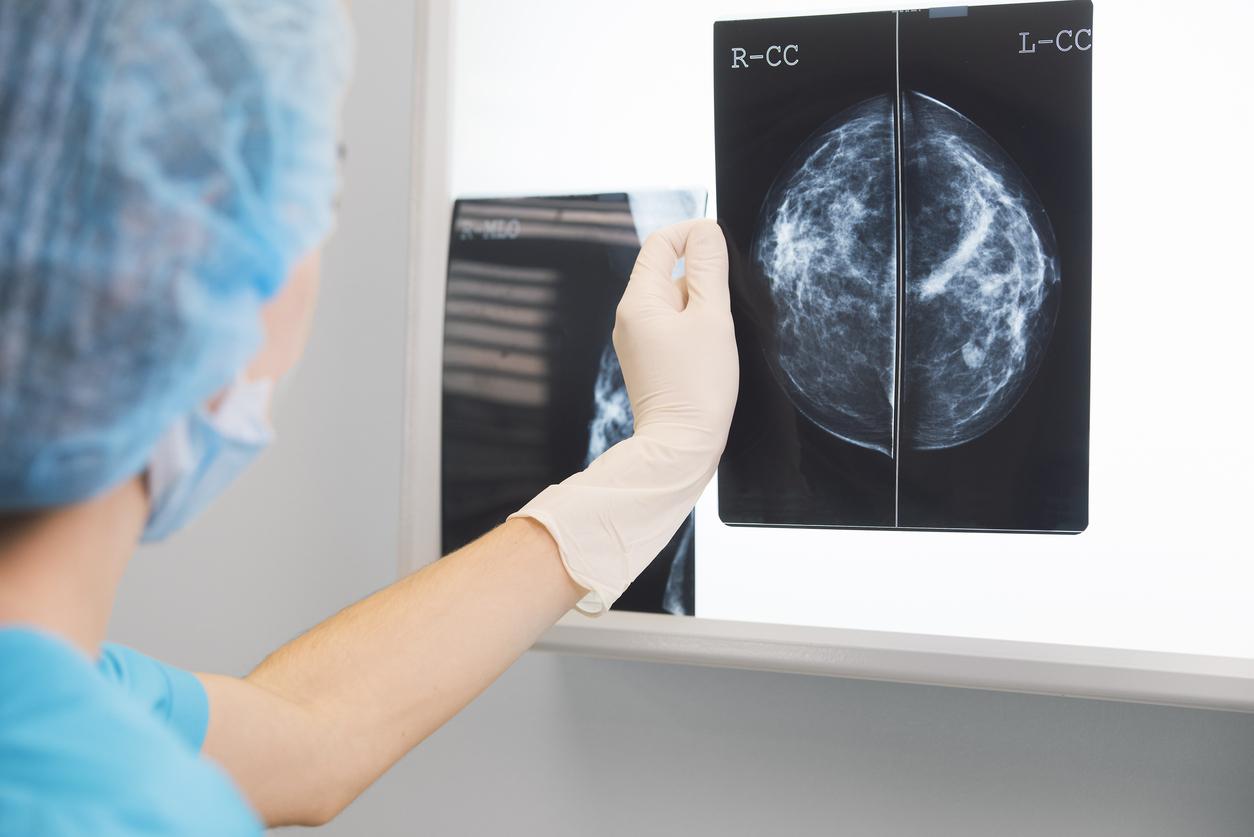

What characterizes triple negative breast cancer compared to other breast cancers?

Triple negative breast cancer is characterized by the absence of hormonal markers that will be characteristic of other breast cancers. It is called triple negative because it is negative for three markers, three specific receptors: HER2 and the hormone receptors progesterone and estrogen. As it is a cancer that we define by default, it is very heterogeneous and we find many types of diseases in this family, hence the difficulty in treating it.

How many people are affected by this cancer?

It represents approximately 15% of breast cancers treated each year in France. Since there are approximately 60,000 new cases of cancer per year, that’s a little less than 10,000 new cases of triple negative breast cancer.

It is said that this cancer is very “aggressive”, how does this translate for the patient?

This means that it carries a higher risk of recurrence and that the overall survival of people with this triple negative is shorter than those with other forms of breast cancer. Another important element is that it is a cancer that is more common in young women, with 40% of patients being under 40 years old.

“Epigenetics is the costume of the cell”

Your field of research is epigenetics, how can you define this discipline of biology for us?

Epigenetics, as its name indicates, is all the information that will be encoded beyond DNA; it is the behavior of cells that is not genetic. All cells in the body have roughly the same DNA, the same sequence, but a skin cell and a nail cell will not be identical. To translate it into simpler words, epigenetics is the costume of the cell! In fact, it is the cell which dresses its DNA, which decorates it with chemical modifications, and this is what allows it to say who it is and what it does.

And what happens when a cell becomes cancerous?

In cancer, this decoration is completely abnormal, it is put in the wrong place, in an aberrant manner while normally the costume is very precise and hyper defined. In fact, cancer cells no longer know exactly how to use their DNA. So we study these changes because what is very interesting here is that these are reversible phenomena! Epigenetics therefore gives us great hope, because it means that we can go back in time and restore the cell to its initial costume. Conversely, when we have a mutation encoded in the DNA, we cannot correct it.

Concretely, how is your research going?

Thanks to the Institut Curie, patients give us samples of their tumor for research. With this data, we will be able to map where the epigenetic modifications are located to, over time, understand how these costumes are changed in response to treatment, for example. This allows us to pose hypotheses to say whether an abnormal phenomenon is happening or not, and above all, to propose solutions to prevent this from happening. Then, using mouse models, or in real patient models, we try to reverse or prevent these modifications from moving, to understand what can increase the response to chemotherapy, or make the cancer less aggressive. , etc.

What are the first results?

We have some ideas on how to prevent a cell from changing its costume, that is to say, we have already identified some epigenetic targets. Today, we are only working on it in animals, in which we are already able to increase survival, but the longer-term idea is to one day hope to find a target that works in humans.

“We are focusing on triple negative breast cancer to identify what we call a therapeutic target”

Do you have any idea how many more years it will take you to achieve this?

It’s difficult to say, we’re talking about several more years, maybe five to ten years before this type of research comes to fruition. But we need major funding support, such as the Bettencourt Schueller Foundation, to carry out this research over the long term.

And what would be the idea: finding a universal drug to treat cancer or rather a molecule adapted to each subtype?

I think that pragmatically, this will rather be adapted to each subtype, to each cancer, because I think it is a bit utopian to think that there is a universal mechanism for all cancers. So we are focusing on triple negative breast cancer to identify what we call a therapeutic target. We will go as far as proof of concept that there is indeed a molecule which can intervene and which could be useful. Once found, we can patent it and hand it over to people who develop drugs.