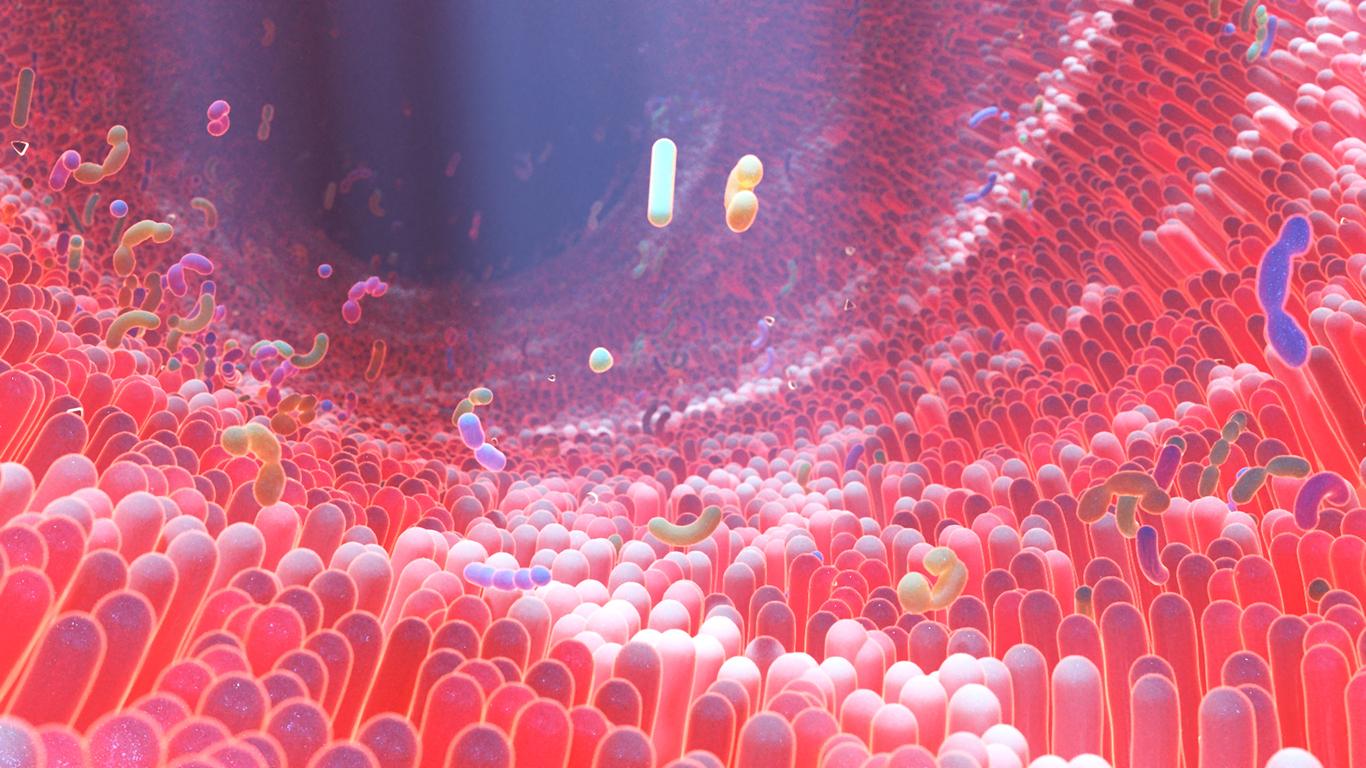

Formerly called the intestinal flora, the intestinal microbiota is made up of fungi, viruses, parasites and especially bacteria. All of these microorganisms are mainly located in the small intestine and the colon. Among them, hundreds of species of bacteria arouse the curiosity of researchers around the world. As long as they are alive, they remain confined inside the digestive tract, ensuring many functions essential to our good health, then they are evacuated in the stool. Each individual harbors a specific microbiota. Even in homozygous twins, its composition differs.

The microbiota begins to set in before birth and continues to develop until around the age of 5. Its diversity is very stable over time, except at the extreme ages of life, in newborns and the elderly. Even though, from person to person, we only have a third of the gut bacteria in common, three ecological organizations dominate: the enterotypes Bacteroid, Prevotella and Ruminococcus. On the other hand, the quantity of each species – and therefore the balance between them all – changes according to our diet (fibers, food additives …), our state of health and our living conditions.

All these bacteria participate in the normal functioning of our organism and in our good health.. Everything that happens in the intestinal environment, including the activity of the bacteria that reside there and what they produce, indeed has an impact on the body in general, via signals that act on the natural defenses, but also the neurons of the enteric nervous system (nervous system of the intestines), then of the brain.

Restore balance

The microbiota thus allows the human body to ensure its daily functions such as defense against infections, nutrition and vitamin synthesis, fat storage and even regulation of our mood. Its balance is essential because, while many bacteria living in the body are “beneficial”, others are “harmful”. The disruption of this balance (dysbiosis) could explain why some people are more sensitive than others to the development of certain diseases and why each responds in a particular way to certain treatments. It is also from these observations that researchers are trying to isolate the bacteria or bacteria responsible for a particular disease, in order to then be able to counteract its action by providing “good bacteria”. We are only at the beginnings and most often the work relates to animal models, so we cannot automatically transpose them to humans. However, current research is raising many hopes, and one certainty is already emerging: it is possible at any time to enrich your microbiota in quantity and quality, thanks in particular to food.