American researchers have succeeded for the first time in creating synthetic human embryos in the laboratory.

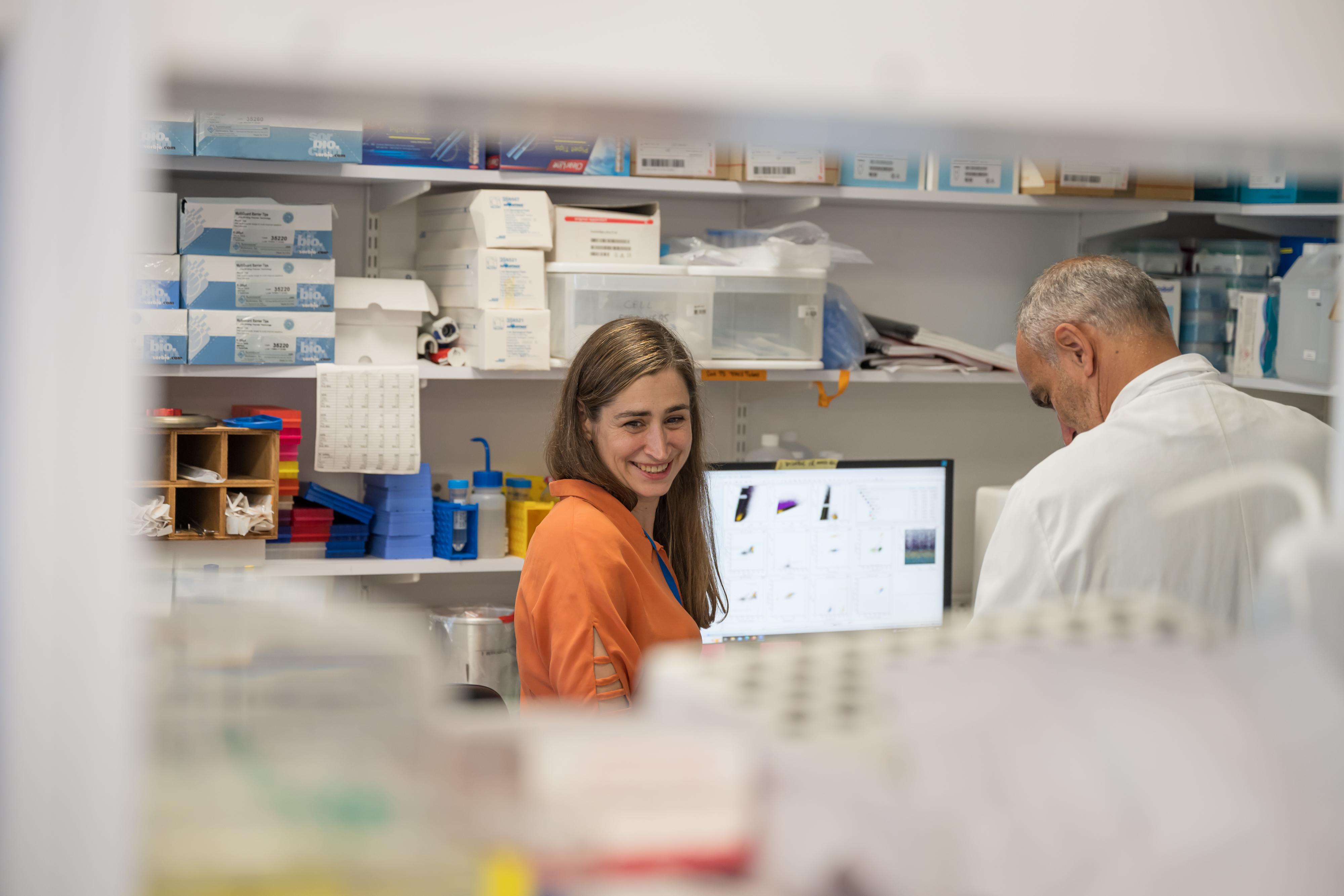

- For the first time, scientists have succeeded in producing embryonic structures from human stem cells.

- This significant advance could be used to better understand the complex processes at play during embryogenesis.

- However, this significant discovery raises concerns.

For the first time, scientists have succeeded in producing embryonic structures from human stem cells in a petri dish, paving the way for new lines of research.

Better understand embryogenesis

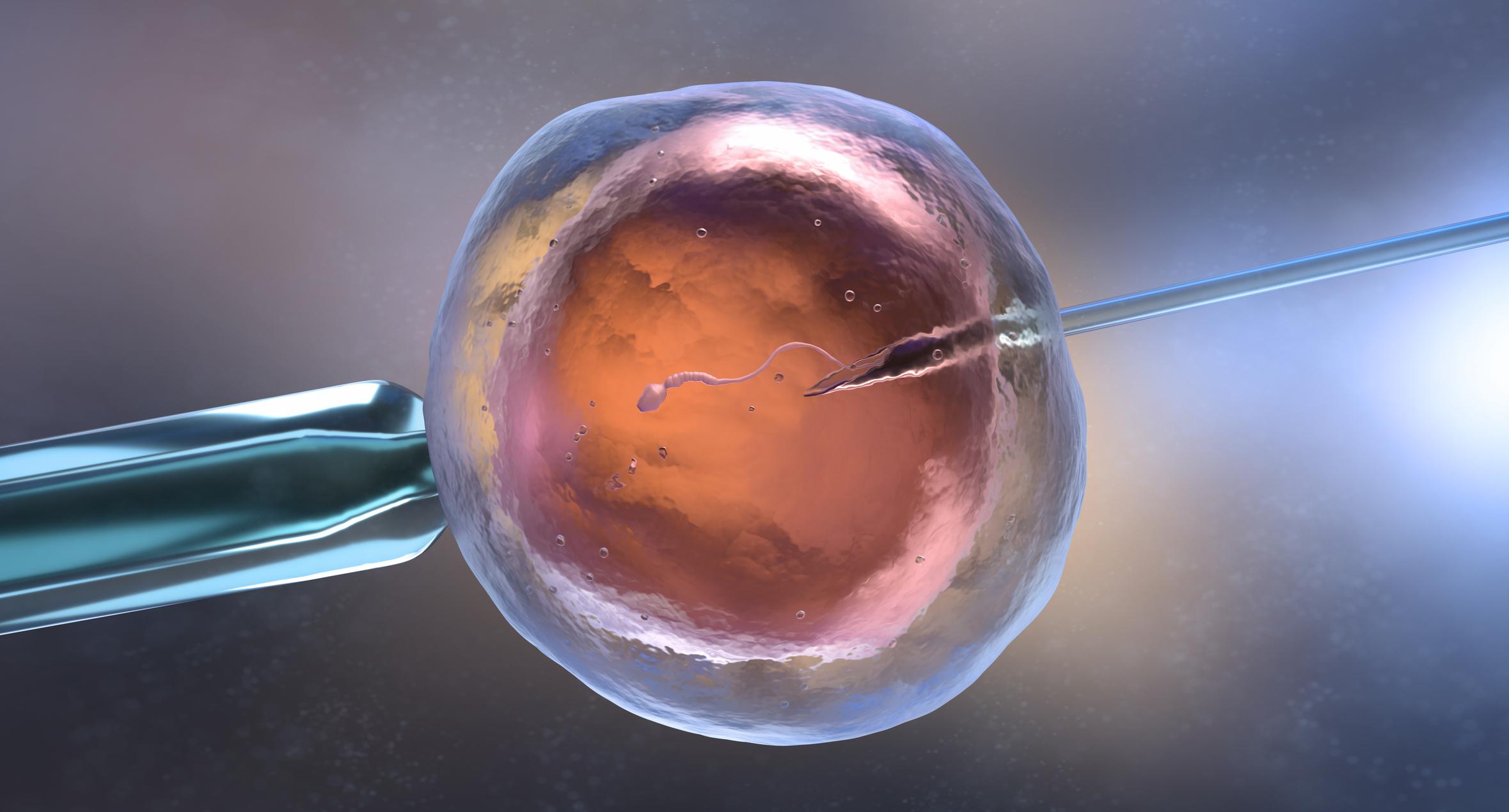

Although the synthetic embryos do not contain a developing brain, they were cultured to a stage corresponding to 14 days of natural development. Scientists claim that their structures cannot be implanted in the womb.

This is a world first, because if such embryos could be created previously, they were produced from animal and not human stem cells.

This significant advance could be used to better understand the complex processes at play during embryogenesis, to better identify genetic diseases, to better treat certain pregnancy-related conditions and to reduce the risk of miscarriage. Furthermore, it opens the door to new opportunities for regenerative medicine.

Concerns

However, this significant discovery raises concerns among many members of the scientific community as well as the general public. Indeed, the issue of artificial reproduction raises serious ethical and legal concerns, as illustrated by the case of GMO babies in China in 2018.

“It is very likely that this research will lead to further debate on the so-called 14-day rule, which is the current legal limit for the use of embryos or embryo-like structures for research purposes. […] Moreover, researchers must ask whether these types of “models” are in fact fundamentally different from human embryos: although they come from different sources and processes, they have similar characteristics to human embryos, which makes the question to know how we view them and deal with them much more complex”, commented Rachel Ankeny, professor of history and philosophy of science at the University of Adelaide to the media Scimex.

“Most importantly, it is essential that researchers are transparent about what kind of research and what is known and unknown, to ensure that our regulatory processes address the necessary issues and that the public is assured that there are mechanisms oversight and adequate safeguards”, she concludes.