The refrain comes up every year: resistance to antibiotics is increasing everywhere and soon we will no longer be able to treat certain infections. A painful observation which is mainly linked to the ineptitude of health policies for 20 years.

We’re going back to the pre-antibiotic era. In 2014, a report on antibiotic resistance predicted that by 2050, antimicrobial resistant infections could become the leading cause of death worldwide.

Recently, a new study published in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases issued an equally alarming conclusion. Among the victims, a majority of children under 12, as well as people aged 65 and over.

These numbers are on the rise. Some of the resistant bacteria studied claimed between three and six times as many victims in 2015 as in 2007, according to the study.

An increase mainly linked to doctors

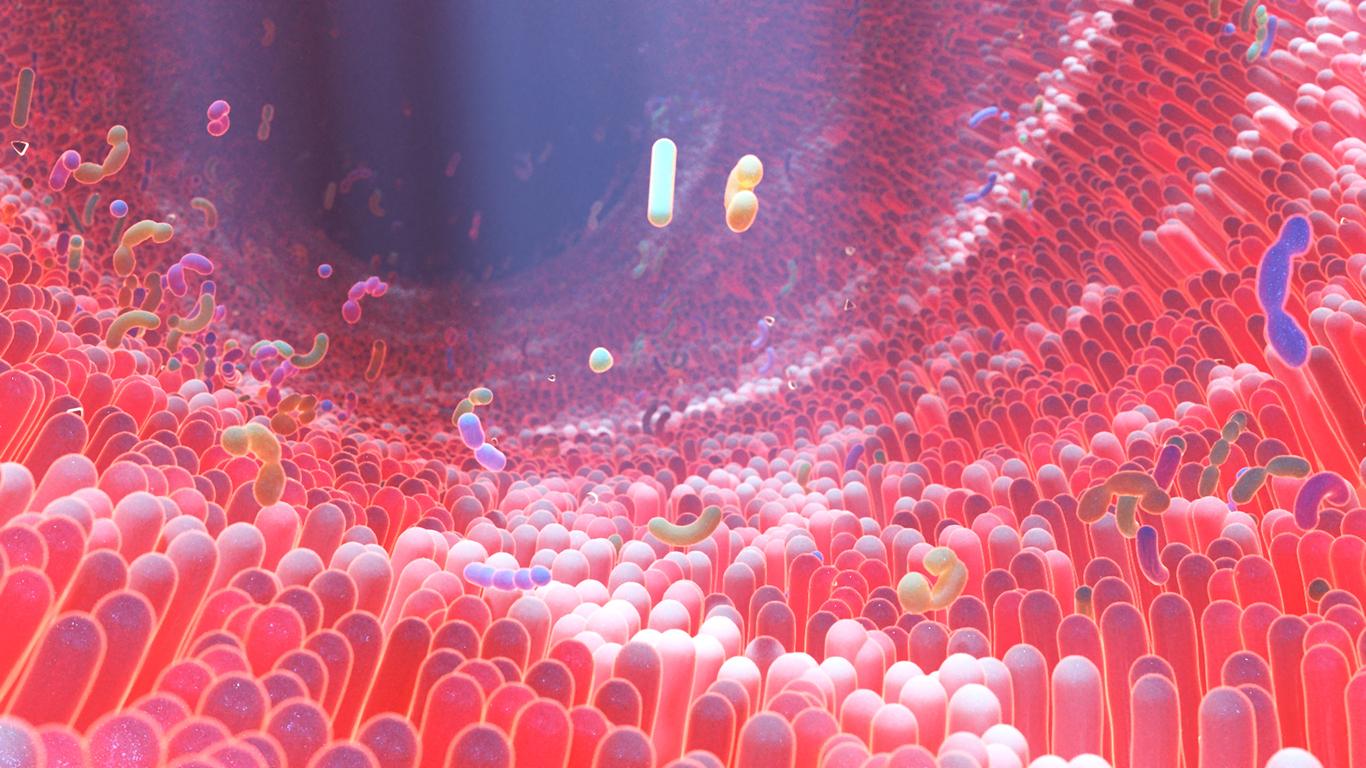

The over-prescription and over-consumption of antibiotics would be the cause of these deaths. In 2015, of the total of 670,000 infections by multi-resistant bacteria, nearly 75% were contracted in a hospital environment. The overconsumption of antibiotics is one of the main factors in the appearance of resistant genes in pathogenic bacteria. These genes can appear by mutation in the presence of the antibiotic, but especially by exchanging genes with other bacteria, including bacteria normally present naturally in the organism, and which would have developed these resistances.

A reduction in the consumption of antibiotics in common infections, which are often viral, is therefore necessary. Recent recommendations and policies attempt to contain this phenomenon, but other solutions are needed.

Research is needed

Other solutions are possible and they depend on medical progress: the development of new antibiotics is still a valid solution. New antibiotics are still being developed despite the difficulties, as evidenced by a new antibiotic which is effective in resistant gonorrhea and whose preliminary results are presented in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The American health authorities, aware of the problem, have placed this drug on the list of rapid approval procedures. Good news for an infection that is constantly increasing in the world and whose bacteria are more and more frequently resistant. But we need sustainable financing solutions.

Research must be profitable

Indeed, if we are there it is because of the “short-termist” policies, brutally put in place by the public authorities over the past 20 years. The main objective of these policies has been to reduce health expenditure at all costs: by reducing the price of antibiotics below the viability threshold, most antibiotic research has stopped suddenly, as well as that on anti-hypertensives elsewhere. Laboratories renowned in infections have just as brutally converted to cancer because it is more profitable and less risky to develop an anticancer drug than a new antibiotic or a new antihypertensive.

Developing an anti-cancer drug takes less time, the studies involve fewer patients and everything is therefore less expensive. There is less risk as well, as it is unfortunately almost normal in cancer to have side effects and even toxic death. This therefore does not necessarily compromise reimbursement and, icing on the cake, with a price level that is generally high.

By swapping reimbursements for antibiotics, which save lives, for those for cancer drugs, which above all prolong lives, “short-termist” policies have cut off the means to develop new antibiotics. As a result, they have incredibly exposed populations to risks that could nevertheless be foreseen. These are not the days of visionaries, at least in the field of infection control.

.