When we are exposed to stress, dopamine, a neurotransmitter, is released by the brain, which helps us to better withstand life’s trials psychically.

- Neuronally, resilient mice have greater activity near their attacker, even early in the response.

- Dopamine stimulation during social avoidance did not make rodents more resilient.

Climate change, pandemic, war in Ukraine… Faced with these anxiety-provoking events, it can be easy to lose all hope. But how is it that some manage to face adversity more quickly than others? Can those who despair learn to be more resilient over time? These are the questions asked by researchers at Princeton University in the United States.

In order to answer it, they carried out work, the results of which were published in the journal Nature. For the purposes of the study, the scientists placed small mice in a cage with larger, aggressive rodents. The goal ? Observe their behavior and examine their neural activity during the 10 days in which they suffered attacks from the aggressor.

“There was something going on in their brains that could be the key to resilience”

According to the authors, the mice that tended not to defend themselves ended up exhibiting “depressive” behaviors, such as social avoidance, after this stressful event. In contrast, rodents that fought back showed greater resilience. “They would turn back at the attacker, they would throw their paws, they would jump on them, and they just wouldn’t give up. I thought there was something going on in their brains that is super interesting and might be the key to resilience”, said Lindsay Willmore, author of the research, in a statement.

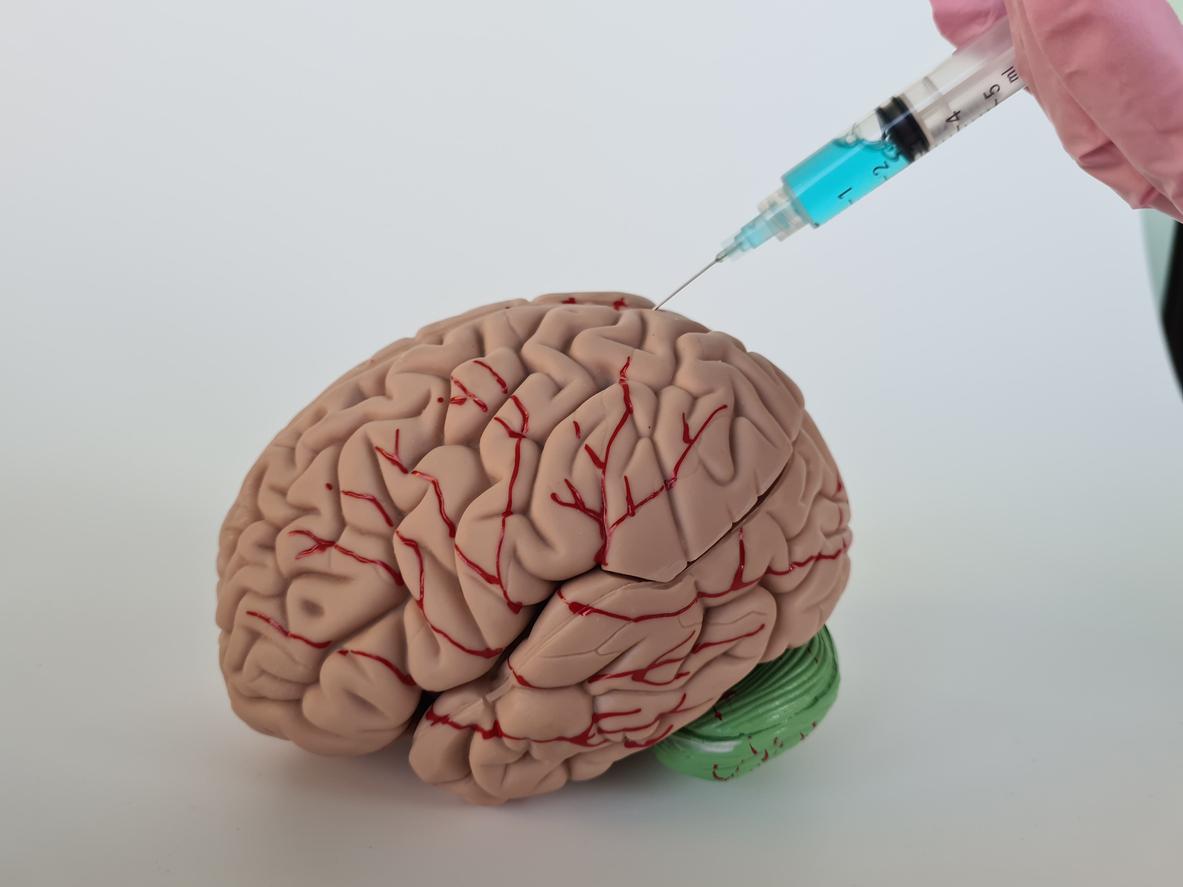

Brain: build resilience by boosting dopamine

By boosting dopamine while the mice fought back, the team discovered that this neurotransmitter could help them cope with this stressful situation more quickly. There was “a link between resilience and the amount of dopamine animals had in their reward system when they began to defend themselves”, clarified Lindsay Willmore.

“We need to think about solutions to help people who seem to be more vulnerable to cope with stress”, said Annegret Falkner, co-author of the study. The researchers hope that in the future, these results can be obtained in human beings. “For example, devices, such as smartwatches, could give real-time insights into good habits to promote healthy mechanisms like resilience,” concluded the team.