In children, hearts considered to be of “bad quality” would give chances of survival equivalent to hearts of “good quality”.

-1579096867.jpg)

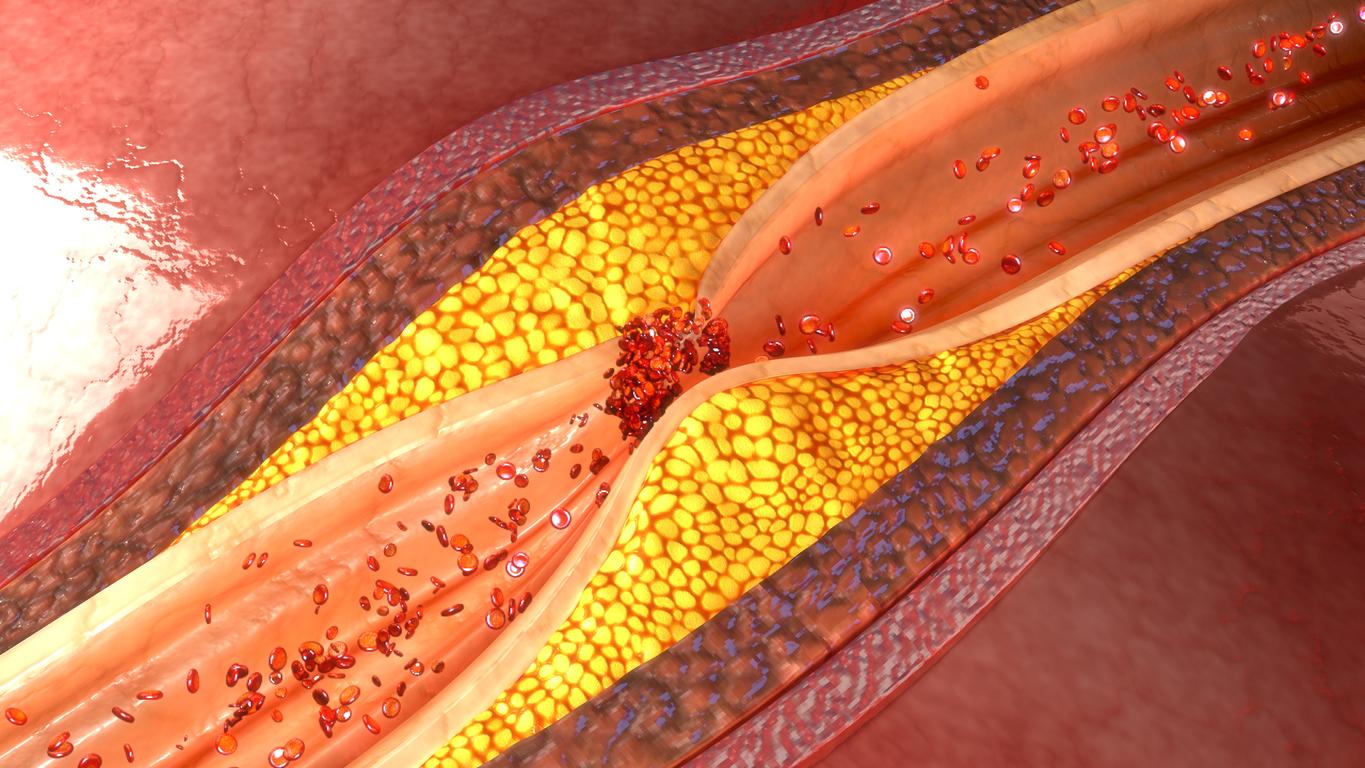

Heart transplantation is a heavy operation, which saves lives every year, but it is a long way to find the ideal donor. In 2017, according to the medical and scientific report of the Biomedicine Agency545 people, including 36 children, were on the waiting list to receive a new heart.

A new study, published in the American journal The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, could bring hope to terminally ill children waiting for heart transplants. According to the findings of this study, many hearts from donors considered high-risk can be transplanted with the same survival rates as hearts from low-risk donors, which could significantly reduce the wait time for heart transplantation.

For Dr. David Morales, director of congenital heart surgery at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (United States) and lead author of the study, this new study could give a chance of survival to many children. “One in five children die while waiting for a suitable donor heart, and some of the potential recipients missed their chance because they were offered donor hearts that transplant programs previously turned down because they believed them to be bad. quality,” explains Dr. Morales.

“These hearts have often been transplanted into other donors with good results. Our study demonstrates that high-risk, or traditionally perceived, donors may have been associated with the worst post-transplant survival because of the recipients they were transplanted into and not because of the donor hearts, says David Morals. While it is important to carefully consider hearts from potential donors for transplantation, these programs should consider accepting hearts from certain donors traditionally considered to be of poor quality.”

The need for a new system

The research team at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (USA) studied the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database for thoracic organ transplants in minors between January 2006 and December 2015. High-risk transplant donors were identified as those over a specified age, those who required cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or those who died of stroke. They correlated low- and high-risk donors with recipient characteristics, and studied survival outcomes for one year. They found that survival outcomes in cases of “high risk” transplant recipients were similar to those of transplant recipients from “low risk” donors.

Currently, transplant institutions do not have a universal system for listing transplant patients. According to David Morales, in the United States, hospitals accept organs and then register patients for transplant according to different criteria, which are not based on the most recent clinical data or on nationally accepted clinical standards. . Rather, they are based on past experiences of the program or provider.

A change in this system is absolutely necessary for David Morales. “We aspire to create a risk-based matching system that matches both the optimal donor and the ideal recipient. We want to achieve the best predictable outcome for each transplant in order to have the highest rate of survival years after transplant for the entire community. The goal is not to achieve transplantation at all costs, but to have as many living and healthy children after transplantation for as many years as possible.”

Work on a standardized model

David Morales and his colleagues received a grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, to study creating a standardized risk stratification model for children, using machine learning to identify the best matches of donors and recipients to maximize survival. This initiative aims to reduce the waste of pediatric thoracic organs and create a better model for organ utilization. According to David Morales, the new model will depend on a data-driven algorithm that will optimize graft matches and benefit all children who need a heart or lung transplant.

Currently, the size of the donor is considered the deciding factor in determining which organs can be offered to a recipient. The problem is that this decision is based on program experience, not national standards. Currently, we have technology that allows scientists to develop methods for accurate comparison of donor organ sizes through 3D modeling, virtual surgery and artificial intelligence. This will increase the use of donor organs for pediatric heart and lung transplants.

“If we let the old systems prevail, many lives will be lost. It is very important to fully understand the range of donor hearts or lungs that can fit into the recipient’s chest cavity, insists David Morales. However, because of current systems, children with end-stage heart failure face the highest mortality rate in all of transplant medicine.”

Dr. Ryan Moore, director of the Heart Institute’s Digital Media and 3D Modeling Program, feels confident about this new protocol. “If new techniques of virtual transplantation are used, the number of acceptable donor hearts for each patient will increase, because the ranges will be individualized based on the size of that patient’s heart and not by a less precise estimate, such as the age or weight.”

.