A nightmare for many women, urinary tract infections (cystitis) could be treated better thanks to a discovery by INRAE researchers.

- Urinary tract infections are the most common community-acquired bacterial infections in women.

- Identifying the regulatory mechanism of a molecule that “feeds” bacteria could lead to the development of new antibiotic treatments

INRAE researchers have understood how a “vampire bacteria” (Enterococcus faecalis), which could make it possible to better fight against urinary and heart infections.

Used in medicine from the Second World War, antibiotics are great allies in the fight against bacterial infections. However, their massive use has led to the emergence of resistance in bacteria, rendering these drugs ineffective.

Detect and measure the amount of heme available

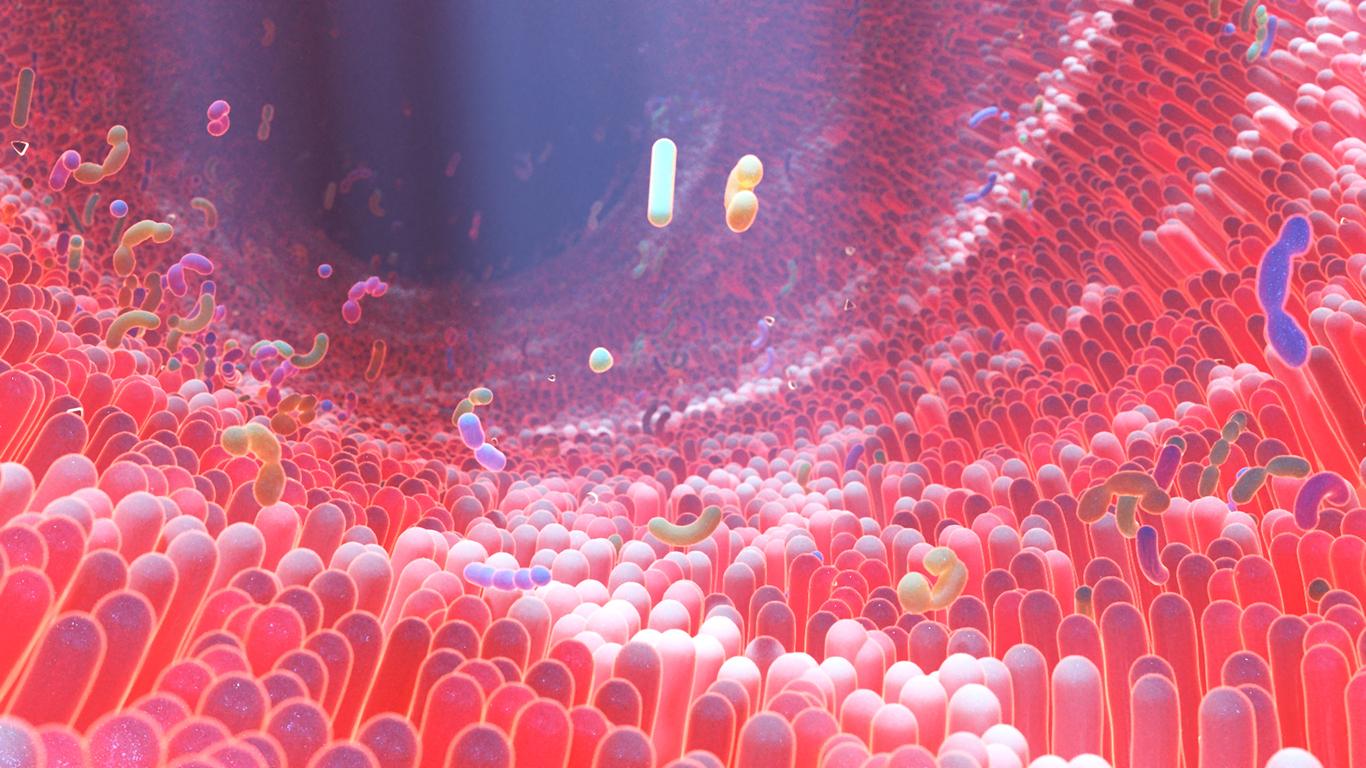

In recent years, researchers have noticed that antibiotics kill not only the bacteria responsible for the infection, but also a large majority of other bacteria present in our body, in particular those of the intestinal microbiota. This raises another problem: not all bacteria are killed, and some, initially harmless, emerge and contaminate the host. Enterococcus faecalis, the 3rd cause of nosocomial infection (contracted in a hospital environment at the time of care) is one of these opportunists. Like many other intestinal bacteria, it must draw from its environment a molecule that it is not capable of manufacturing: heme*. This molecule, essential to the development of the bacterium, becomes toxic if it is present in too large quantities.

Based on these assumptions, INRAE researchers studied the ability of Enterococcus faecalis to find enough heme in the intestinal environment to meet its needs, while avoiding the toxic effects of this molecule. This is how they discovered a mechanism that allows the bacteria to detect and measure the amount of heme available.

“An innovative and complementary antibiotic approach to current treatments”

Their work, published on February 2, 2021 in mBio, uncovers a brand new molecular pump in this bacterium, activated by a sensor that detects the amount of heme. We now know how and when this pump is active: at low concentrations, heme enters the bacteria passively. When there is too much, the pump is activated and rejects the excess heme out of the bacteria. Enterococcus faecalis is therefore able to “feel” the presence of heme and to activate its pump to eliminate what could be fatal to it.

“The discovery of this mechanism of regulation of heme transport in Enterococcus faecalis allows an advance in the understanding of the physiology of this opportunistic pathogenic bacterium”, conclude the scientists in a press release. “Showing that this mechanism is essential for the survival of Enterococcus faecalis during infections and blocking it could constitute an innovative antibiotic approach that complements current treatments”, they congratulate each other.

*Heme is a molecule containing iron present in the blood in large quantities and allows the transport of oxygen. It gives its red color to blood.

.