Hemochromatosis is a genetic disease. One of its mutations is often described as “Celtic”. A study shows that this disease was imported in the Bronze Age.

The Irish live on an island, but their genome comes from overseas. A research team bringing together the two parts of the Green Island (Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland) analyzed the genome of primitive men. The work, published in the journal of the American Academy of Sciences, PNAS, irrefutably demonstrate the mass immigration that took place there. But above all, they question the idea that a mutation that causes hemochromatosis – a genetic disease that results in excess iron in the body, is of Celtic origin.

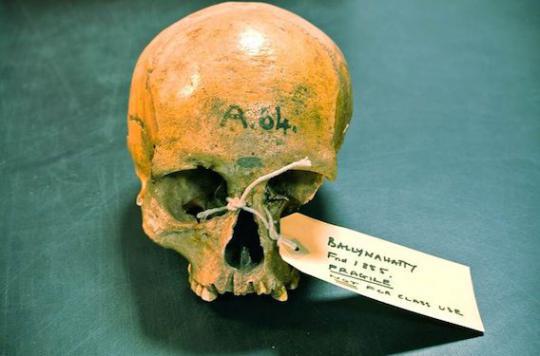

Four early Irish men served as the basis for this work. The first was a farmer who lived in Ballynahatty, near Belfast (Northern Ireland, UK) 5,200 years ago. The other three lived further south about 4,000 years ago. The sequencing of their genome has elucidated the mystery of Irish genetics – which crosses many European branches and presents many variants encoding lactose tolerance, the Y chromosome of Western Europe or hemochromatosis.

A late mutation

In the latter case, the mutation is very common among the Irish. So much so that the mutation that causes it is often considered a Celtic disease. But it could well come from elsewhere. Indeed, the primitive cultivator draws her ancestors from the Middle East and exhibited features more akin to southern Europeans: black hair and brown eyes. In its genome, no trace of hemochromatosis.

This genetic mutation does not occur until later, in men of the Bronze Age. A third of their ancestors come from the Pontic Steppe, north of the Black Sea. These men have the alleles that code for the blue eyes that we know today among the Irish people… and the variant that causes hemochromatosis. The disease would therefore have been imported.

“A great wave of genome alteration has taken place and swept across Europe from the northern Black Sea to Bronze Age Europe, and we now know that it spread as far as ‘on the shores of its westernmost islands, explains Dan Bradley, co-author of this study. This degree of genetic modification gives rise to the possibility of other associated modifications, perhaps even the introduction of ancestral languages from which the Western Celtic languages will emerge. “

.