INTERVIEW – From basic research to clinical practice, the Neurocampus de Bordeaux intends to compete with the best world poles for neuroscience research.

This Thursday, the Neurocampus of Bordeaux was officially completed, with the inauguration of the Broca center. With its 650 French researchers, but also European and international researchers, the center, which brings together the Bordeaux University Hospital, teams from Inserm, CNRS and Inra, the group presents itself as a center of excellence for neuroscience research.

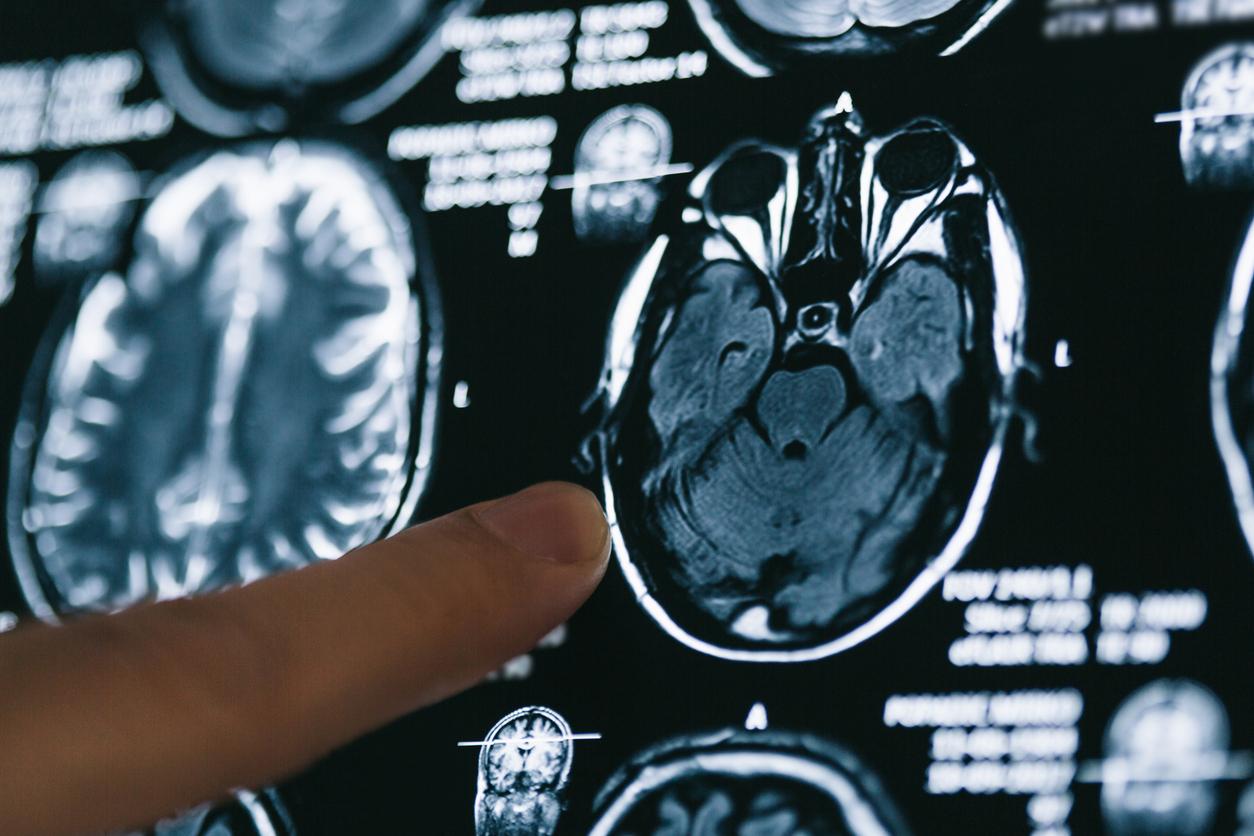

The Broca center inaugurated this Thursday will have cost 67 million euros, largely funded by the regional council. It now brings together activities ranging from basic research to the clinic, from the cell in the laboratory to the patient in the hospital.

By its scope of activities and its attractiveness, the managers of the Neurocampus of Bordeaux want it to compete with European research centers, and even American universities.

Christophe Mulle, director of the structure, explains to Why actor the progress and challenges of grouping activities on the Bordeaux campus.

What will the activities of the Broca center be?

Christophe Mulle: It is part of a real campus, with buildings connected to each other, with research laboratories, a school of neurosciences, and the Bordeaux University Hospital, therefore directly linked to the clinical aspect of research. There are, in all, 50 teams, each with its own specialty. It is a multidisciplinary center with a multitude of expertise. Within these teams, major themes emerge: neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s, and the mechanisms of addiction. We are also trying to bring digital technology into neuroscience-related technologies on subjects such as sleep.

How did the city of Bordeaux become a national benchmark in neuroscience?

Christophe Mulle: The history of neuroscience in Bordeaux is quite old. The name of Broca was not chosen by chance, since he was from Bordeaux (Paul Broca was a doctor from the 19e century that carried out research in neurology, editor’s note).

More recently, it has been 20 years since the community of neuroscience researchers in Bordeaux began to develop, in particular with the inauguration of an Inserm building which was specifically intended for them. This is what attracted many teams to Bordeaux, including mine.

We also had extremely regular and significant support from the Aquitaine Regional Council, at the time, to equip us and bring in new teams. Then, in 2008, we convinced him to invest heavily in neurosciences, and that is why the Regional Council funded the Broca building.

Is this structure capable of competing internationally?

Christophe Mulle: This is the idea. At the national level, we already have very good visibility. We have succeeded in doing something collective, with the support of the public authorities and Inserm, CNRS and Inra. The community aspect is visible, because we are all gathered around this Neurocampus. At European level, we are also trying to be up to the task. And if the support continues, we should make it happen thanks to outstanding research teams who have trained themselves, and excellent productivity. We are on an international standard.

On the occasion of the inauguration, we organized an international congress on the past, present and future of neuroscience research. The many high-level researchers from all over the world who were present were all stunned by the evolution of Bordeaux neuroscience over the past 15 to 20 years.

Is this regrouping by major poles the future of French research?

Christophe Mulle: I think that’s a direction things are going, indeed. The big French universities can no longer afford to sprinkle resources on all themes, and they are focusing on certain strong axes. The Great Loan obliges to concentrate resources on certain disciplines, and in certain places. We cannot do without this structuring effect, and therefore to make choices on the themes to be developed. And the General Council understood this well. Initially, he wanted to invest in oncology. An audit was ordered, which made him change his mind in favor of neuroscience, because there was already a well-established research fabric.

Does Bordeaux’s recognized attractiveness help attract researchers?

Christophe Mulle: We arrived at the right time, at a time when Bordeaux started to change its look. I started my studies in Bordeaux, and 20 years ago, it was a city that was not at all attractive. She was bourgeois, sleepy, dirty… We are now able to attract people thanks to the quality of life, and of the city. The post-docs are delighted to be in Bordeaux, because it is a beautiful city, of a good size, where there is a lot going on. This is an argument that serves us!

.