Women still live longer than men, according to an INSEE study. And a gap persists between managers and workers.

Life expectancy. This is an area in which women are the winners. Whether workers, employees or managers, they live longer on average than men. According to the latest study by INSEE (National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies), life expectancy has nevertheless increased more among men since the 1970s. But not enough to make up for the considerable advance of the fair sex.

Better medical monitoring

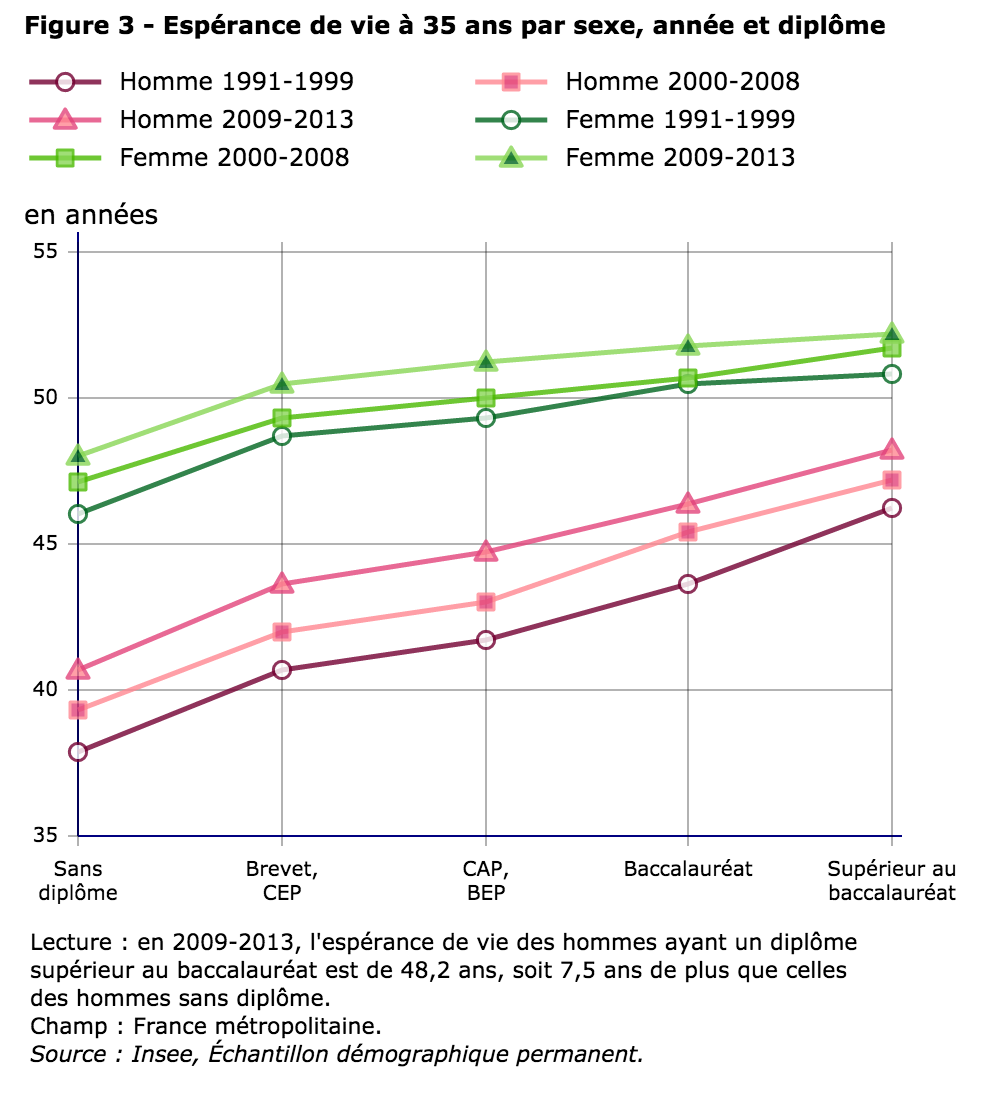

At the age of 35, a woman can hope to live another half century. This number must be amputated by five years to obtain the life expectancy of men. The gap is such that female workers – who are the least advantaged socio-professional categories – live longer than male executives – the most advantaged.

At first glance, this may seem paradoxical: women’s incomes are lower than their male equivalents, working conditions are more difficult. Two parameters which should affect life expectancy. Except that women have a behavior favorable to their health, underlines INSEE: they consume less alcohol and tobacco, benefit from better medical monitoring. And above all, they leave with a biological advantage. So many factors that explain the gap between the two sexes.

The chicken or the egg?

Environmental factors also help to explain the differences between socio-professional categories. For men, the higher the diploma, the longer the life expectancy increases. Among women, there is a dropout between graduates and non-graduates. But the gradation according to the level of studies does not take place.

Professionally, this level of education affects access to employment. The most qualified will access the most qualified positions, which maintains the gap. Executives thus live 6 years longer than workers. This time, the very nature of the job comes into play: “executives are less subject to occupational risks (accidents, illnesses, exposure to toxic products, etc.) than workers”, underlines INSEE. At the same time, they are more likely to take charge of their health. The Institute does not fail to note that the analysis works in both directions: a health problem can prevent the pursuit of studies and therefore access to a highly qualified position.

.