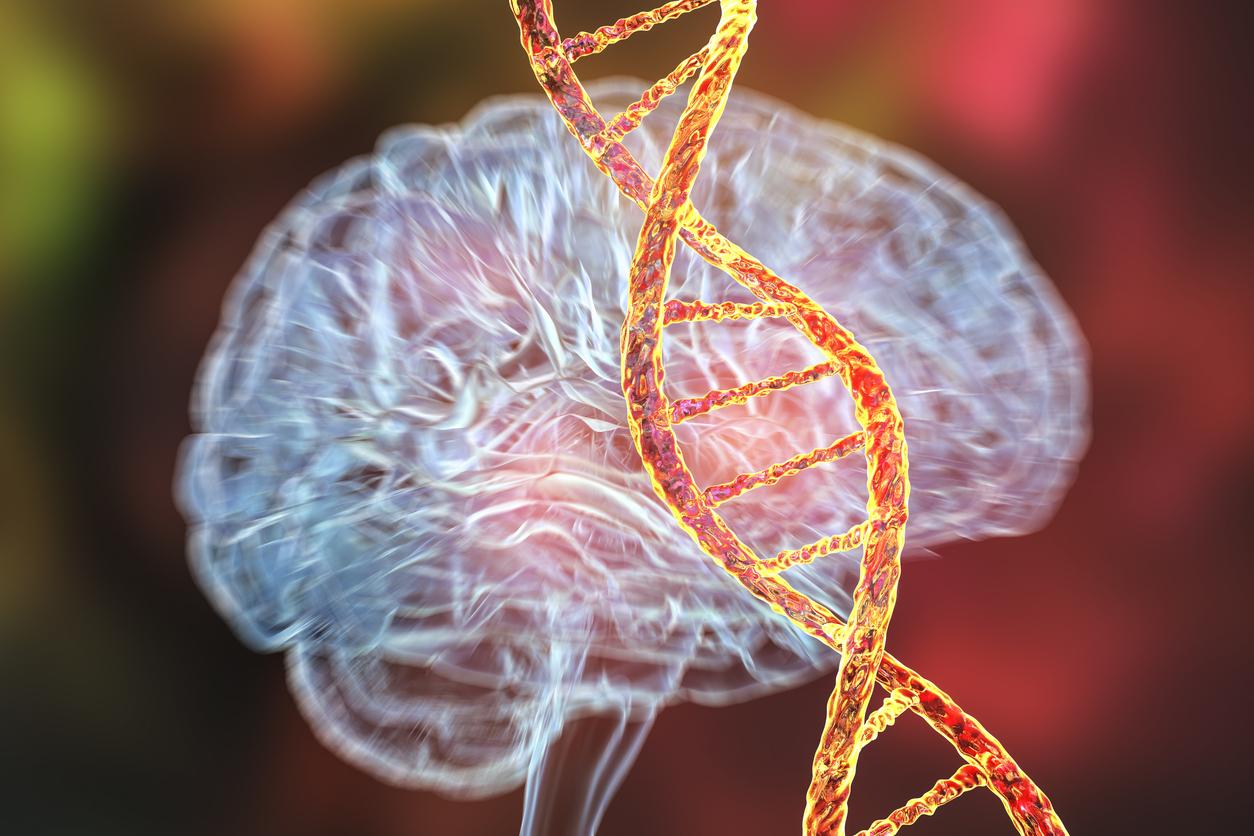

Our prehistoric ancestors developed a key gene to better digest starch from carbohydrates, which would explain our pronounced taste for starches and sugars.

- Our difficulty cutting carbs may be linked to an ancient genetic adaptation. The AMY1 gene, responsible for the production of amylase, an enzyme that breaks down starch, was duplicated in our ancestors more than 800,000 years ago.

- The more copies of this gene we have, the better we digest carbohydrates. This adaptation, present among hunter-gatherers long before agriculture, intensified with diets rich in starch.

- Understanding this genetic variation could offer new avenues for better managing carbohydrate metabolism and digestion today.

Having trouble resisting the temptation of pasta and bread? What if it was simply ingrained in your DNA? A new study led by the University of Buffalo and the Jackson Laboratory in the United States reveals that our ancestors evolved a specific gene to better digest starch, an essential component of foods rich in carbohydrates. This gene, called AMY1is responsible for the production of amylase, an enzyme that helps break down starch in the mouth: the more copies of this gene we have, the more efficiently we can metabolize this type of food.

A genetic ability to better digest carbohydrates

As part of their work, published in the journal Scienceresearchers discovered that the first duplications of the gene AMY1 occurred more than 800,000 years ago, well before the appearance of agriculture. This discovery overturns the theory according to which adaptation to a diet rich in starch was linked to agriculture. In reality, our hunter-gatherer ancestors already had between four and eight copies of the gene AMY1allowing them to digest the starchy foods they found in nature.

Gene duplications AMY1 have also been observed in Neanderthals and Denisovans, two ancient human species, indicating that this genetic adaptation is very ancient and dates back to a period when human and Neanderthal evolution had not yet diverged.

The study reveals that the more copies of the AMY1 gene we have, the more amylase we produce, which makes it easier to break down starch into glucose, a source of energy for our body. “The idea is that the more amylase genes you have, the more amylase you can produce and the better you digest starch.”summarizes Professor Omer Gokcumen, who participated in the work, in a press release. This increased ability to better digest carbohydrates would have provided an evolutionary advantage to humans, particularly during periods when high-carbohydrate diets became more common with changing technologies and lifestyles.

The impact of the advent of agriculture on our genes

With the advent of agriculture, the quantity of gene copies AMY1 continued to increase. In Europe, for example, agricultural populations saw their average gene copy number AMY1 increasing from four to seven over the last 12,000 years. This adaptation was favored by the regular consumption of cereals and other foods rich in starch. Individuals with more copies of the gene were likely able to digest these foods better and, therefore, were healthier and more able to reproduce. These adaptations, shaped by thousands of years of evolution, continue to influence how our bodies respond to carbohydrates today.

Note that this evolution is not limited to humans. Domesticated animals living alongside humans, such as dogs and pigs, have also had their gene copy numbers lowered AMY1 increase, allowing them to better digest the starchy diets provided by humans. Research into this genetic variation could, according to the researchers, have important implications for health, particularly with regard to starch digestion and glucose metabolism.