The last Ebola epidemic in West Africa claimed a record number of victims, but it also has 17,000 survivors. How do they live after such an infection? This is what Inserm (National Institute for Health and Medical Research), IRD (Institute for Research and Development), and the Donka University Hospital in Guinea wanted to know.

The researchers followed 802 of the 1,270 people who survived the infection in Guinea to determine the impact of the disease on their current lives. A year after their first hospitalization, three quarters of them still have health problems linked to Ebola. Fatigue and fever in the first place, for 40% of participants, but also muscle pain (38%) and abdominal pain (22%), visual problems that can lead to blindness (18%) or anemia (a quarter of former patients). “The frequency of these symptoms fortunately tends to decrease over time and they become less significant as one moves away from the acute phase of the infection,” explains Eric Delaporte, director of the Mixed Unit international “Translational research on HIV and infectious diseases”.

A need for long-term follow-up of patients

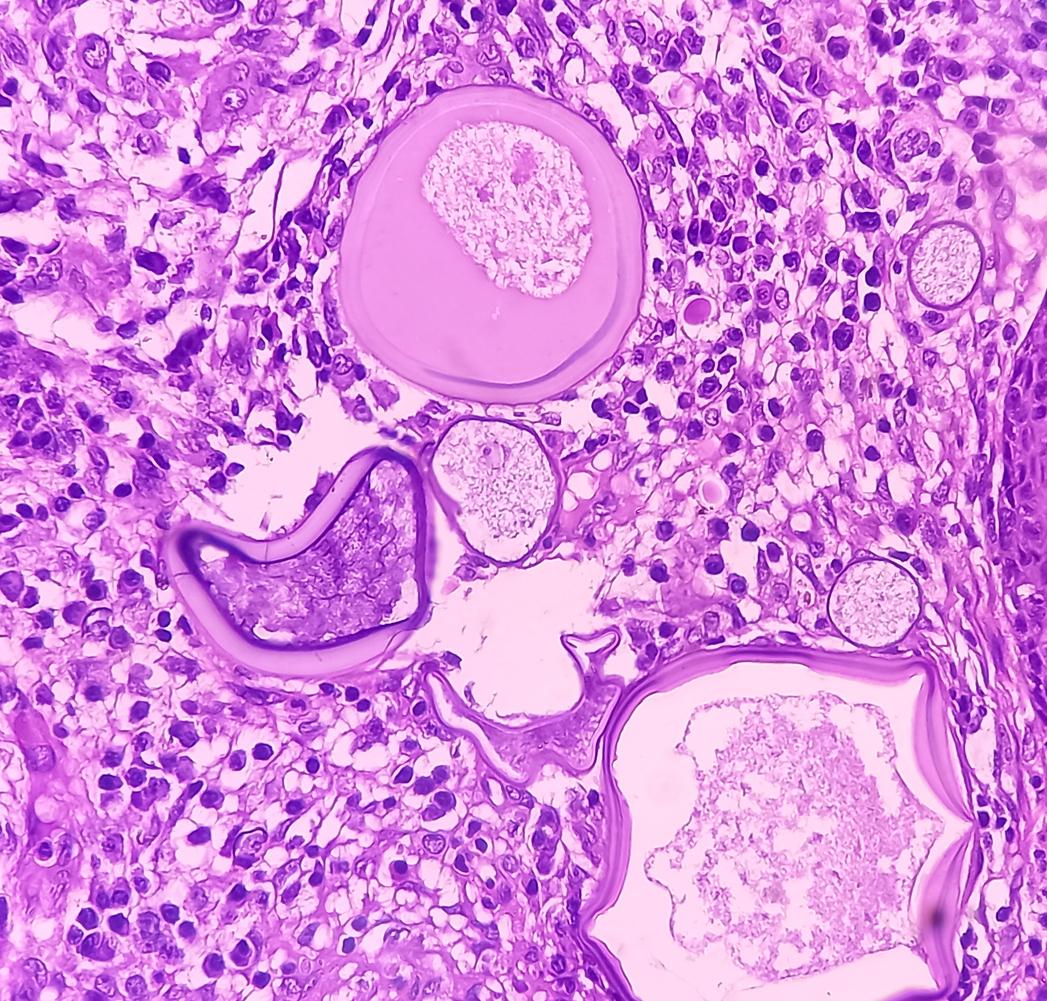

In their study published in Lancet Infectious Diseases, the scientists refer to these disorders as post-ebola syndrome, but they are not the only consequences of the disease. Patients also suffer psychologically – 17% report depression – and socially – one in four is stigmatized by this episode.

Participants joined the PostEbogui cohort on average one year after their infection. In addition to biological, psychological and sociological monitoring, the scientists measured their viral load after 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months of entering the study. They found that for 5% of men, it remained detectable in the semen a year and a half after the initial infection with the Ebola virus. For Eric Delaporte, “the results of this first large cohort […] justify that a medical follow-up of patients with Ebola be carried out at least for 18 months following the infection”.

Also to read

Finally a vaccine against Ebola

Ebola virus persists for nine months in semen

Ebola is no longer an international emergency