The Canadian federal government has been collecting data for ten years on deportations and treatments imposed on Inuit in the 1950s.

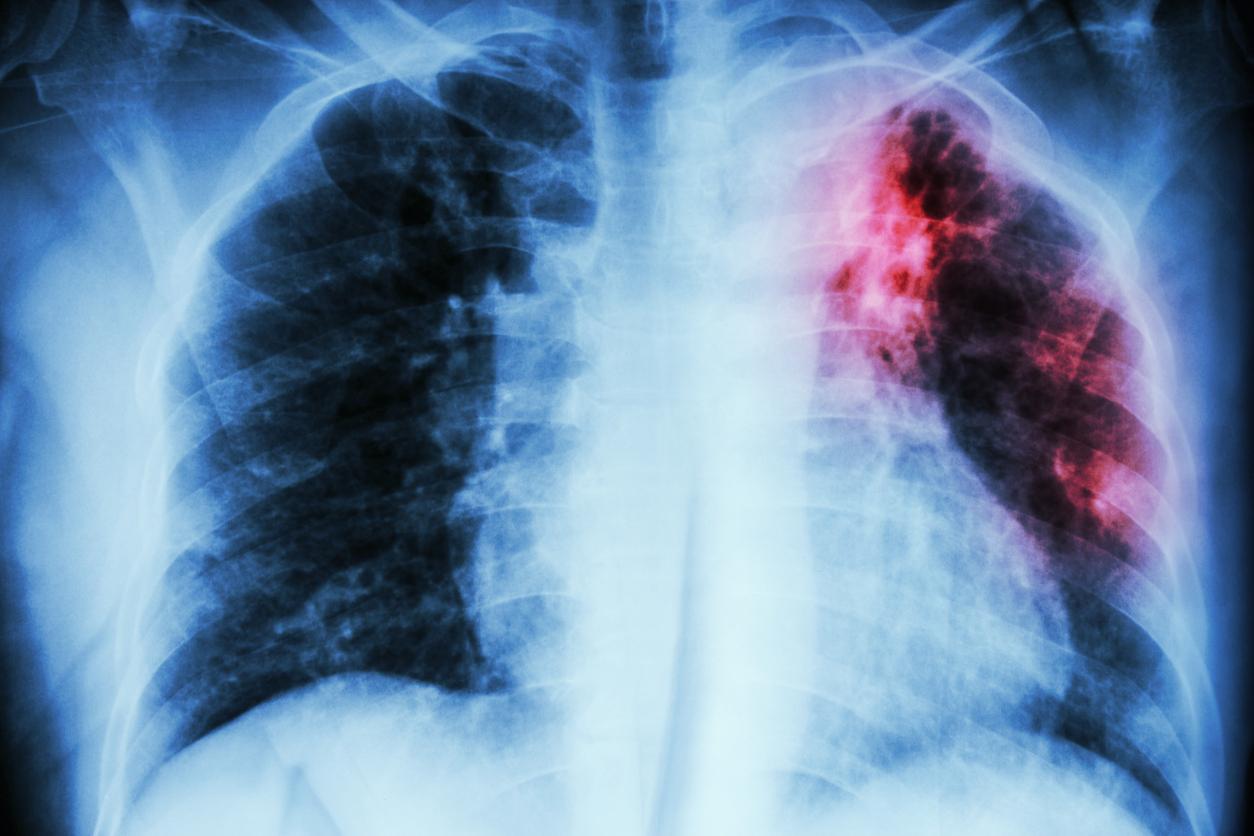

5,240. This is the number of Inuit, children and adults alike, who were displaced between 1953 and 1961 by the Canadian authorities, out of the 11,500 in the native community at the time. They had been sent to the south of the country to be treated for tuberculosis.

For many of them, this journey had no return. And their families have not received any information on the fate of their relatives. Not even on the location of their graves.

But after more than 50 years of silence, the Canadian federal government should soon release some of this information, which has been gathered over the past ten years, reports the Canadian site. Lapresse.ca.

Let’s find them

In 2008, the Nanilavut program – which means ‘let’s find them’ – was launched. A team of researchers searched federal, provincial and territorial archives, religious registers, cemeteries or hospitals, and collected personal testimonies.

The data is still incomplete, recognizes Elizabeth Logue, program manager. But information, even partial, has been found for around 4,500 displaced Inuit.

“Some files contain details on treatments and the return of patients to their community,” reports the Canadian site. Other files only speak of the treatments received, without specifying whether the patient survived or not. Files mention a death of the patient, but without details on the place where the body was buried. Finally, a few files contain all the necessary information, from treatment to the place of burial. “

Uprooted sick

In 1946, an epidemic tuberculosis outbreak severely affected the Inuit community in northern Canada. The coast guards were then sent to recover the sick, and transport them to hospitals in the south of the country for treatment.

Displacement continued into the 1950s, and even until the 1970s, which saw the end of the epidemic. But the children, sometimes very young and away from their families for several years, had for some forgotten their language.

Others, adults and children, were sent back to communities that were not theirs. And for many, who died in hospital or sanatorium, no information about their death was communicated to the families.

To close a chapter

Children whose parents had been displaced searched for them for years. One of them, Jack Anawak, a former MP, was eight years old in 1956 when his mother was deported. She died two years later, but the family never knew where she was buried.

“We always wonder where our loved ones are,” he says. For me, it is very important that we can close the last chapter of our lives. To finally know where our mothers and fathers are and to be able to visit them. Some Inuit are said to still be looking for relatives, believing them to be still alive.

Ghosts of the past

The work of the Nanilavut group is not finished, but the authorities want the data already available to be made accessible now. Some have already been able to consult the data.

Elizabeth Logue also wants the consultation to go through community groups, and not individually, so that the context and history are well explained. “Seeing this information for the first time could wake up trauma,” she says. There will be support offered. “

This sad episode in Canadian history, which is part of a tradition of mistreatment of Indigenous populations, would still have repercussions today. Sociologists believe that if tuberculosis continues to circulate in Inuit communities – which today are 50 times more affected than the rest of the population – it is in part because of these forced displacements.

.