A new study finds a worrying rise in cases of silicosis, a lung condition once seen in underground miners and now affecting craftsmen working with artificial stones.

- A study points to the resurgence of silicosis, formerly called “miners’ disease”.

- At issue: the work of artificial quartz agglomerate, an artificial stone used for kitchen and bathroom counters.

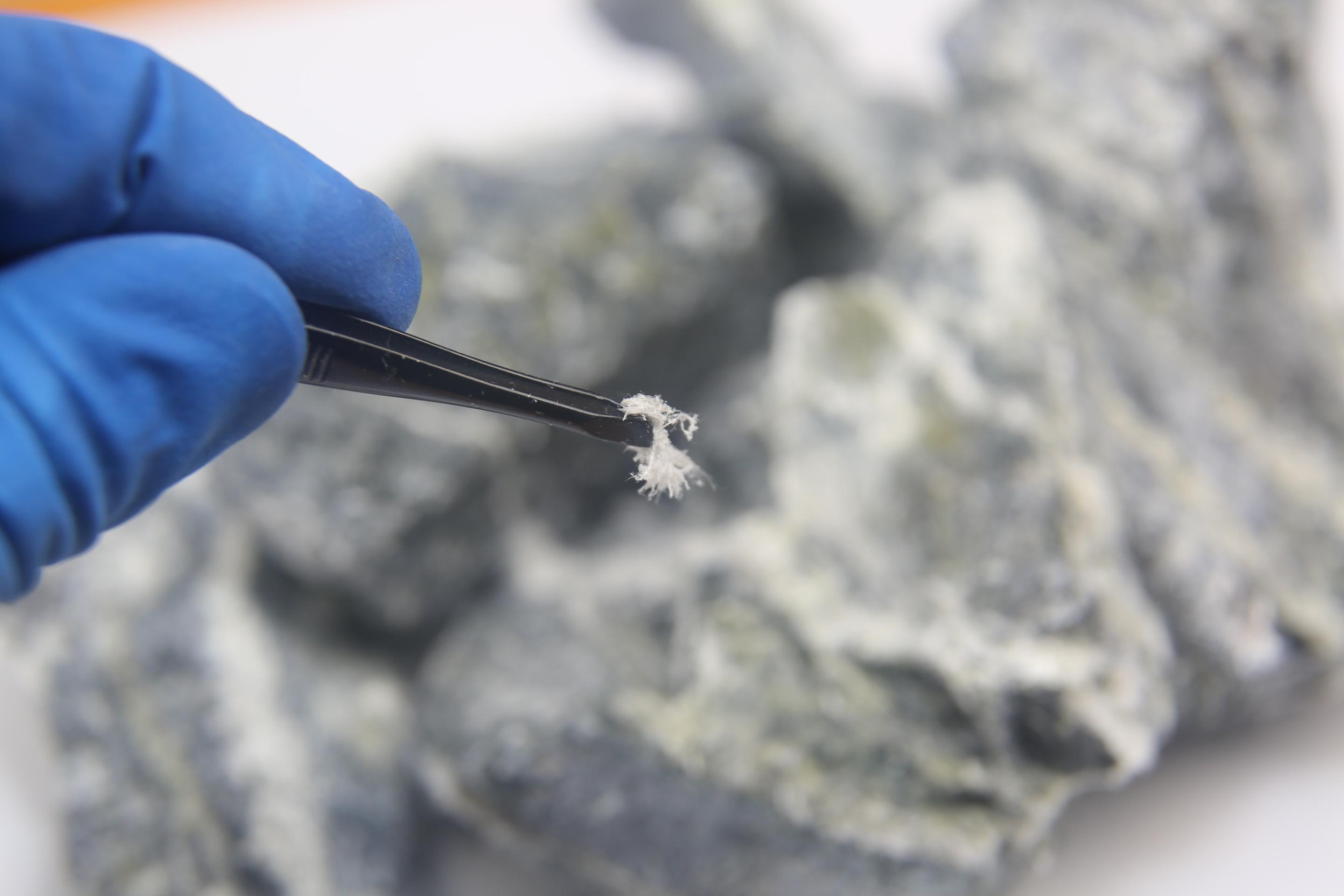

Considered the oldest occupational lung disease, silicosis is a condition affecting miners, quarry workers, stone cutters and even coal miners. It is the consequence of inhaling tiny particles of silica (crystalline silica) in mines, quarries, tunnel borings or building and public works sites.

According to a new study published in the journal CHEST, silicosis is far from having disappeared. It would even be on the rise with artisans and workers working with artificial stone, called artificial quartz agglomerate, a new material used in particular for kitchen and bathroom counters.

6.6% of workers concerned

Conducted among 106 workers in southern Spain with silicosis or severe pulmonary fibrosis between 2009 and 2018, the study shows that the inhalation of artificial quartz agglomerate dust significantly increases the risk of developing these two diseases.

Composed of finely ground stones mixed with synthetic resins with a high silica content, the artificial quartz agglomerate emits, during its manufacture or its cutting, respirable crystalline dusts which can cause permanent damage to the lungs when inhaled .

“While 6.6% of workers were initially diagnosed with massive pulmonary fibrosis, 37.7% had more advanced disease on follow-up examination, even though they had quit their job and were no longer exposed to the harmful dustexplains Antonio León-Jiménez, researcher in the Department of Pulmonology, Allergy and Thoracic Surgery at the Puerta del Mar University Hospital and lead author of the study. In a quarter of patients, the rate of decline in lung capacity progressed very rapidly.”

New essential protective measures

While protective measures have already been adopted to better protect cast stone workers from dust inhalation, such as the use of water suppression techniques and exhaust ventilation, cases of silicosis continue to grow, especially in small workshops and factories, which are not always well equipped.

For the authors of the study, it is essential that more restrictive technical controls be carried out, and that new treatments against silicosis be developed and tested. “Avoiding continuous inhalation of silica is essential, but it is not enough. The majority of patients are young and the progression of the disease in a significant number of them suggests an uncertain future. Our findings underscore the need to maximize protective measures in active patients and to find new treatments that may delay or halt disease progression.”concludes Dr. León-Jiménez.