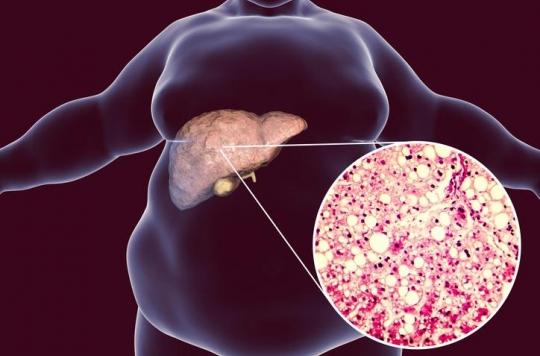

Caused by too much sugar in the liver, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, or NASH, is a disease with few symptoms in its early stages, which can delay diagnosis and complicate management. A handset released by our intestinal bacteria could help detect it early, says a consortium of European researchers.

Also known as “fatty liver disease” or “club soda disease”, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NASH) is a silent, symptomless disease that insidiously breaks down the liver. At issue: excessive consumption of sugar and fat, which can lead to liver failure and, ultimately, cirrhosis or cancer.

While people with obesity, high blood pressure or type 2 diabetes are at greater risk of developing fatty liver disease, the fact remains that the diagnosis is very often made too late, when liver damage are irreversible and therefore require a transplant.

An in-depth analysis of intestinal biomarkers

For several years, however, researchers have been trying to find ways to diagnose non-alcoholic fatty liver disease earlier, so that it can be treated as quickly as possible. A European consortium (FLORINASH) bringing together French, Italian and English researchers from Inserm, may have achieved this by collating data from two cohorts of 800 men and women suffering from obesity, and by separating the groups according to the presence or absence of “foie gras”.

Then the researchers analyzed the medical data of 100 obese women with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease but no diabetes. Blood, urine, stool, and liver biopsies samples were taken and were then compared with similar samples collected from healthy individuals. Detailed analysis of the data revealed the presence in people with NASH of high levels of a compound called phenylacetic acid. Released by certain intestinal bacteria, it is thought to be due to the accumulation of excess fat in the liver and the early onset of fatty liver disease.

“Through this work, we may have discovered a biomarker for the disease itself,” says Dr Lesley Hoyles, of Imperial College London in the UK, to the journal Nature Medicine. “Overall, it shows that the microbiota definitely has an effect on our health.” If phenylacetic acid is indeed a biomarker of hepatic steatosis, this gives hope for the development of an early diagnosis of this affection by a simple blood test.

NASH can change the composition of the gut microbiota

Another discovery made by the researchers: that according to which NASH could change the composition of the intestinal microbiota. When the disease is noticed, the number of genes encoded by intestinal bacteria gradually decreases, suggesting that the microbiota becomes poorer and less diverse in its microbial composition.

According to scientists involved in the study, a less diverse microbiota can cause metabolic problems such as inflammation of the liver and unresponsiveness to insulin, the hormone that helps regulate blood sugar levels. .

“From the intestinal microbiota to fatty liver, we have marked out all the stages up to inflammation. This has enabled us to identify bacterial molecules at the origin of steatosis and hepatic inflammation”, explains Prof. Rémy Burcelin at The Dispatch.

Hope for a screening blood test

The scientific team now wishes to continue its research around the signals produced by intestinal bacteria and which could, in the long term, make it possible to diagnose diseases at an early stage. “This opens up the possibility that a simple screening test in a clinic […] could one day be used to detect the first signs of the disease “, rejoices Prof. Marc-Emmanuel Dumas, researcher at Imperial College London.

However, it will take years for a screening test to be clinically tested. To get there, researchers need to refine their understanding of phenylacetic acid and its role in the diagnosis of fatty liver disease. “We now need to explore this link further and see if compounds of phenylcetic acid can actually be used to identify patients at risk and even predict the course of the disease”, continues Prof Dumas.

The idea is also to be able to lead to the development of a new generation of probiotics and to a pharmacological strategy interfering with the bacterial mechanisms responsible for hepatic disease. “The good news is that by manipulating gut bacteria, we may be able to prevent fatty liver disease and its long-term cardiometabolic complications,” the researcher concludes.

.