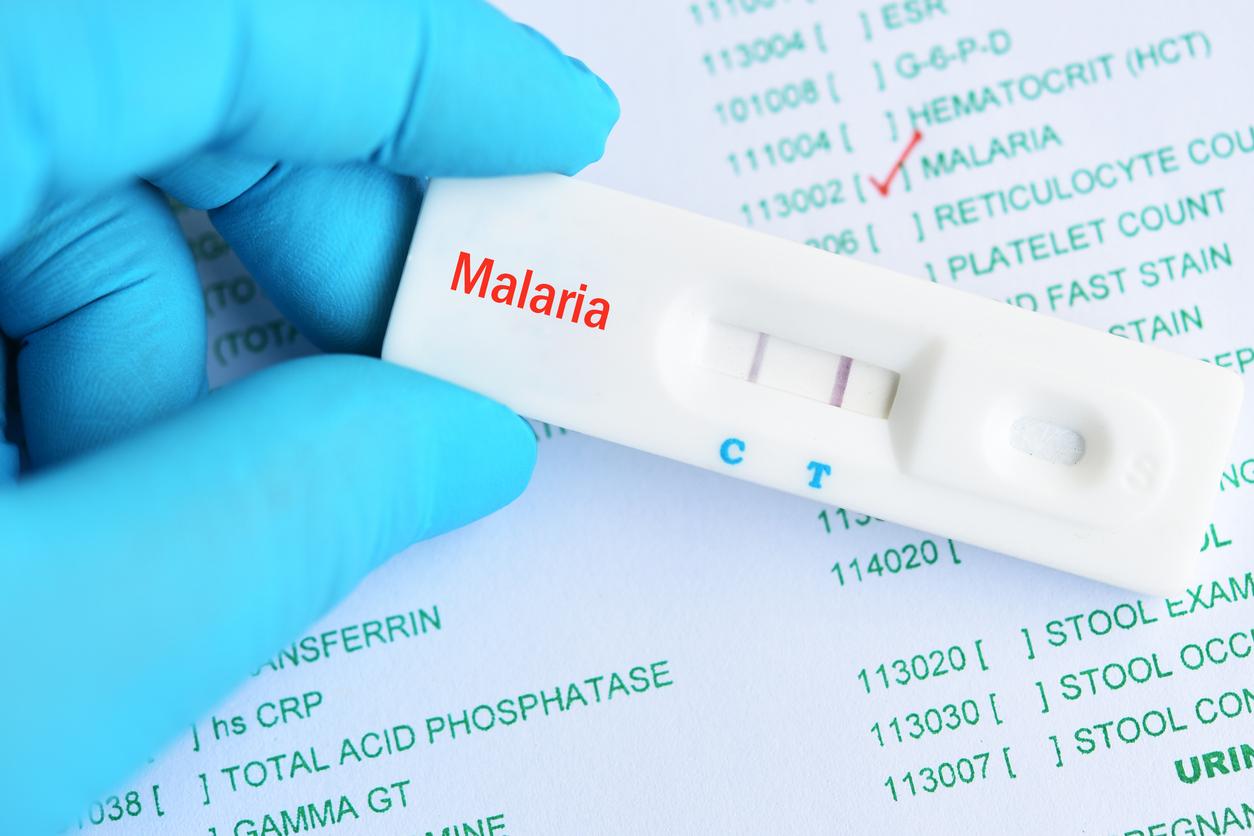

Researchers at the Institut Pasteur in Lille have identified an essential gene specific to the parasite responsible for malaria. Ultimately, this discovery could contribute to the creation of new therapeutic targets.

Despite a decline in malaria-related mortality over the past fifteen years, the WHO has counted around 435,000 died worldwide in 2017, with the victims mostly children living in sub-Saharan Africa, where the disease is so common it is called swamp fever. The latter is caused by the bite of a female mosquito, of the Anopheles type, itself infected by the Plasmodium parasite.

Unfortunately, at present, there is no effective vaccine against malaria and the main treatments are therapeutic combinations based on artemisinin, a principle derived from a plant, and Plasodium is becoming more and more resistant to it. Also, in order to continue the decline in mortality observed in recent years, researchers must quickly develop innovative drugs. An unprecedented French discovery could, however, contribute to the creation of new therapeutic targets. Indeed, researchers have identified an essential gene specific to the parasite, announced the Institut Pasteur de Lille in a press release on October 14.

By studying the specific mechanisms of Plasmodium biology, Dr. Jamal Khalife’s research team (CNRS, Inserm, University of Lille, Institut Pasteur de Lille) succeeded in demonstrating that it was possible to intervene genetically on GEXP15, a protein specific to the parasite, thus reducing its virulence and blocking its development in the mosquito.

Sub-Saharan Africa and India concentrated 80% of the total number of cases in 2017

“This study characterizes for the first time a new molecular pathway of an essential regulator of PP1 (Protein Phosphatase type 1) and specific to Plasmodium, which could contribute to the discovery of new therapeutic targets to fight against malaria”. congratulates the Institut Pasteur.

In 2017, the number of malaria cases worldwide was estimated at 219 million. Transmission occurs in 91 countries, mostly in poor tropical areas. That same year, fifteen countries in sub-Saharan Africa and India concentrated 80% of the total number of cases in the world.

“In France, the departments of Guyana and Mayotte are the only areas of the territory where malaria is present. In mainland France, cases of malaria are observed almost exclusively in people returning from countries where malaria transmission is active”, notes the Ministry of Health on its website. In 2018, the number of imported malaria cases was estimated at around 5,280 for the whole of metropolitan France.

Plasmodium falciparum can kill

In terms of symptoms, when a person falls ill, malaria begins 8 to 30 days after the mosquito bite. She starts to have a fever. The latter can be accompanied by headaches, muscle aches, weakness, vomiting, diarrhea and coughing. Cycles alternating fever, tremors and intense sweating can then take place.

When properly treated, the primary infection heals within a few days. But its evolution varies according to the parasitic species in question. In people with malaria Plasmodium vivax and to Plasmodium ovale, relapses can occur several weeks or months after the first infection, even if the patients are no longer in the area affected by malaria. And in subjects with Plasmodium falciparum, the complications can be very serious. Seizures are manifested by a very high fever (41-42°C), serious neurological disorders with impaired consciousness (convulsions, coma, signs of meningitis) and various general signs (significant anemia, hypoglycemia, coagulation disorders and haemorrhages, damage to the liver and kidneys ). If the patient is not treated quickly, malaria Plasmodium falciparum may worsen suddenly, leading to death.

This is why before leaving for an endemic area, malaria prevention must be systematic, recommend the French health authorities. It is based on the prevention of mosquito bites with the use of a mosquito net, long clothing and mosquito repellents, and the taking of antimalarial drugs.

.