Living in staggered hours disrupts the nocturnal activity of the bacteria that inhabit your intestines, according to a study which highlights the risks of “jet lag”.

Flying to New York, working at night or partying until the early hours… We all have good reasons not to sleep. But our bodies don’t like much – and our bacteria even less, especially those that make up our intestinal flora.

The bacterial clock

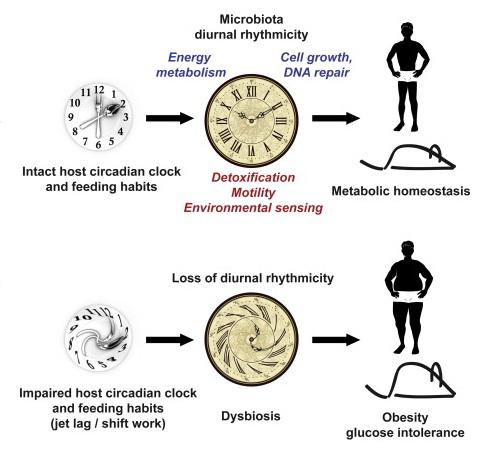

Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel have discovered that these microorganisms that make us up also have their internal clocks. At night, when we sleep, bacteria are working. They digest nutrients, repair their DNA, take care of their growth … But when we watch, this activity is turned upside down.

For the needs of the study, published in the journal Cell, the researchers analyzed the feces of rodents and humans at various times of the day. They noticed that the number of intestinal bacteria, their type and their biological activity differed depending on the time of sample collection. These oscillations are controlled by the circadian clock – that is, which follows a 24 hour biological rhythm.

Then, the researchers disrupted the internal clock of their subjects. The humans took a long haul from USA to Israel. The mice, meanwhile, stayed at home, in their laboratory. Scientists simulated jet lag travel by manipulating light sources and altering meal times, the other component, along with sleep, of the biological rhythm.

Risks of obesity

And the results seem convincing. In both humans and mice, the change in biological rhythm was associated with the occurrence of metabolic disturbances. In fact, in the “jet-lagged” subjects, the researchers observed an increase in the number of bacteria responsible for obesity, and an increased activity of the latter.

Positive point (for those used to sleepless nights): the phenomenon is reversible. In all subjects, the microbiome – the population of bacteria – returned to normal after a few weeks of a more regulated lifestyle.

Other studies have already shown the risks associated with staggered working hours (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, etc.), but until now, this link has remained mysterious. According to Eran Elinav, author and co-author, this study sheds light on the body clock and its impact on overall health. “These surprising results could be used to develop preventive treatments to limit these risks in people whose day-night cycles are regularly disrupted”.

.