Migrant women are three times more likely to have severe pregnancy complications compared to those born in France.

For immigrants, arriving in France does not always sign the end of the galley. This is especially true for women. Compared to French women, expatriates are more at risk of complications during their pregnancy. However, they represent one in five births.

Parturients from sub-Saharan Africa are particularly victims of this inequality, as revealed in the latest Weekly Epidemiological Bulletin (BEH).

In an issue dedicated to the health of immigrant populations, the review of Public Health France devotes an entire article to gynecological and obstetric care that benefits – or not – women who have chosen to leave their native country. And they are clearly disadvantaged from the start of their gestation.

Isolated populations

Compared to native French women, immigrant women go to consultations less often during their pregnancy. The example of 9,700 patients in the establishments of the Paris-Nord Hospital Group shows this clearly. More than a third of those from sub-Saharan Africa were not followed up properly, as were a quarter of women from North Africa.

Among native French women, only 17% did not receive adequate follow-up. This gap is widening even more among women who have recently settled in France. This is all the more true if they are in a precarious situation. The explanations for this inequality relate to both migratory status and social context.

Pregnancies are less often planned, occur at a young age and concern women with little education. If we add to this the lack of mastery of the French language, in some cases, and the lack of social coverage, many obstacles stand in the way of access to healthcare. What the authors of this article denounce.

Inappropriate follow-up

“Insufficient attention is paid to structural inequalities, linguistic competence, migration background or discrimination”, deplore Inserm researchers. They also point to the “social distance between doctors and patients”.

In addition to this irregular follow-up, patients of foreign origin also do not have the same access to the appropriate examinations. 78% of them do not receive the care recommended by health authorities and learned societies. This rate climbs to 95% among women from sub-Saharan Africa.

Compared to those born in France, immigrants will benefit less from systematic monitoring of arterial hypertension by automatic blood pressure monitor over long periods. And if the control of protein in the urine is carried out more often, alarming indicators are more often overlooked.

Three pathologies dominate

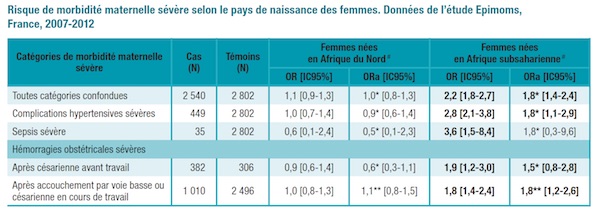

The consequences of this lack of attention can be catastrophic. Compared to native French women, women from sub-Saharan Africa are three times more at risk of severe maternal morbidity. Since 2007, the record has improved for women from North Africa.

Three pathologies clearly dominate the picture of maternal illnesses. Immigrant women are twice as affected by severe complications linked to pregnancy-induced hypertension, by severe obstetric haemorrhages. The occurrence of a sepsis severe is also three times more common.

This sad observation confirms the interest of prenatal follow-up, in particular in the prevention of sepsis. This work shows to what extent suboptimal care and late diagnosis promote the progression of a disease to a severe stage.

This article also recalls that genetic risk factors must be taken into account, especially in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Here again, a lack of follow-up can prove to be deleterious for the mother as well as for the child.

.