The release of DNA by these white blood cells traps pathogens but also causes clots to form. A mechanism demonstrated by the work of a young French researcher, Karen Aymonnier, who has just been awarded the 2020 prize for young researchers awarded by the Bettencourt-Schueller Foundation.

– Why Doctor: What led you to do this work on the action of neutrophils?

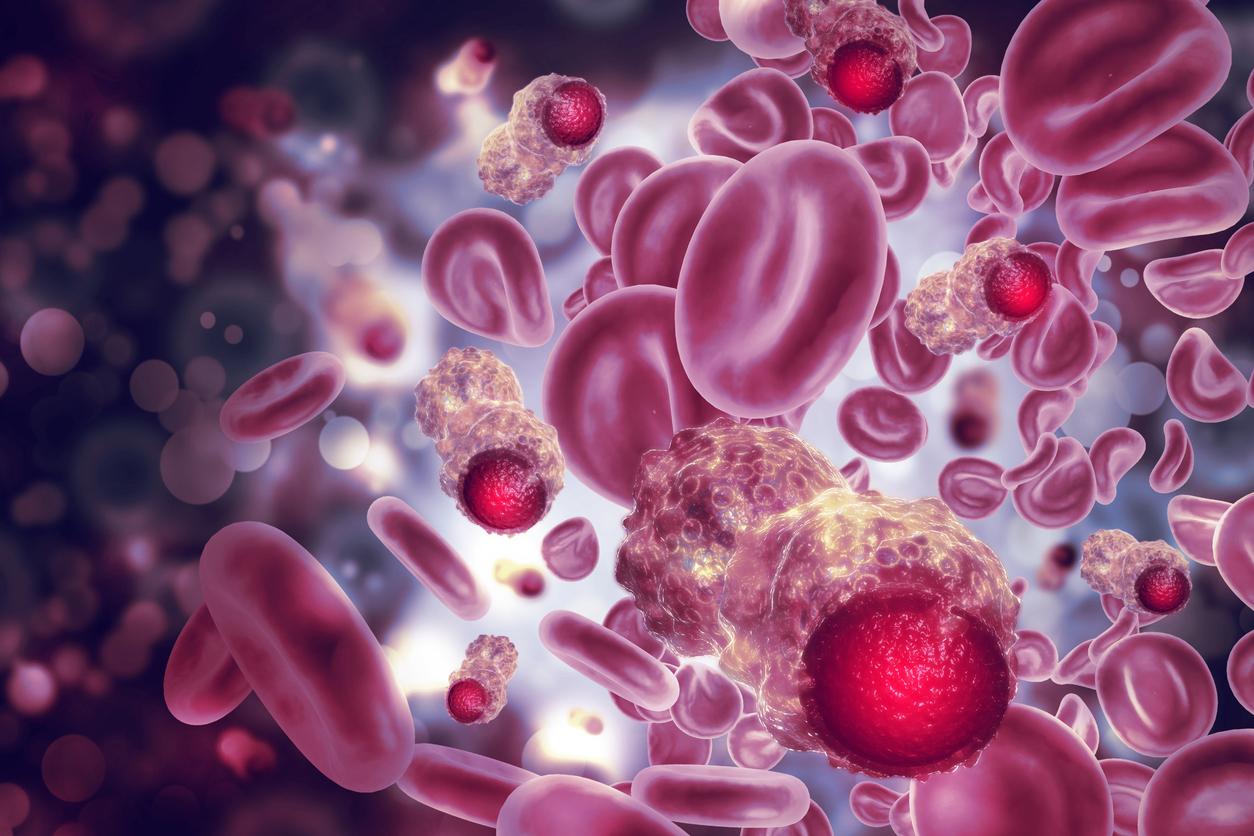

Karen Aymonnier : I worked very early on the mechanisms of inflammation and inflammatory pathologies. In parallel with my thesis on the mechanisms of hemophilia, I had the opportunity to work on these neutrophils, white blood cells mainly present in the blood – they represent 60 to 80% of the white blood cells circulating in the blood – and are linked to the mechanism of thrombosis, in fact the activation of neutrophils participates in the formation of blood clots. There really is a very strong interconnection between inflammation and coagulation.

– How can an inflammatory reaction trigger thrombosis?

K.A. : These neutrophils, as soon as there is an infection, that is to say an invasion by an external pathogenic agent, are the first to intervene on the site of the infection. It’s a bit like policemen in the blood: as soon as something not very good happens in the body, they immediately go to the place of infection or inflammation and then s activate by secreting cytokines and proteases, to prevent pathogens from spreading through the body. And one of their mechanisms to fight against these pathogens is to release their DNA at the site of infection, and these long strands of DNA will form like a trap for bacteria or for viral particles. They will trap these pathogens like “spiderman” traps his enemies in a spider’s web! This is a phenomenon that was discovered 15 years ago and which we now know is involved in many pathologies, in particular autoimmune pathologies such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis. And more recently we have seen that these “NETs” (Neutrophil Extracellulr Trap: extracellular neutrophil traps), these cobwebs, can serve as a basis for the recruitment of blood platelets and therefore be at the origin of the formation of blood clots.

– Is this the phenomenon that we observe in some patients with severe forms of Covid-19?

K.A. : Indeed, we talk a lot about it in the Covid with patients who arrive in intensive care with significant pulmonary problems, who present an acute respiratory distress syndrome and are predisposed to arterial and venous thrombosis. We have been able to observe in his patients a lot of NET present in the mucus of their lungs and we have found in Covid patients an increase in NET present in the blood plasma which could further aggravate the risk of thrombosis.

– Does this make it possible to envisage new avenues for treating the phenomena of thrombosis in infections?

K.A. : Yes, it’s really a “hot topic” (important subject, editor’s note) in science. Because neutrophils are a two-sided thing. There is a positive side and a negative side and we should manage to regulate them. Neutrophils are needed to control infection and eliminate pathogens, but they promote even greater inflammation with the risk of developing thrombotic disease. We must therefore find a way, and several studies are looking for it, to limit the formation of these NETs.

I have a very concrete example, in my research team in the laboratory, we launched a clinical trial with Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital on people who develop a severe form of Covid-19. There are many patients who arrive in intensive care and who are put on a ventilator to help them breathe better. To try to evacuate the mucus which accumulates in their lungs and which limits the oxygenation of the blood, they will be administered DNAse, an enzyme which cuts the strands of DNA in the mucus. This DNAse is already administered to patients with cystic fibrosis who have a lot of mucus that clutters their lungs and we have also seen that there was a lot of NETS in the bronchial secretions of these patients.

One of our post-docs who was here returned to France at the start of the epidemic to launch the same clinical trial.

– What are the other possible applications of your work?

K.A. : My work consists of analyzing the cellular mechanisms that lead the neutrophil to release its DNA, to form NETs and how platelets adhere to these NETs. We have seen in several studies that NETs are very involved in all respiratory infections. But this can also occur in infections affecting other organs: this is a phenomenon that is encountered in many pathologies, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. So there’s an application that’s broader than inflammatory lung disease.

.