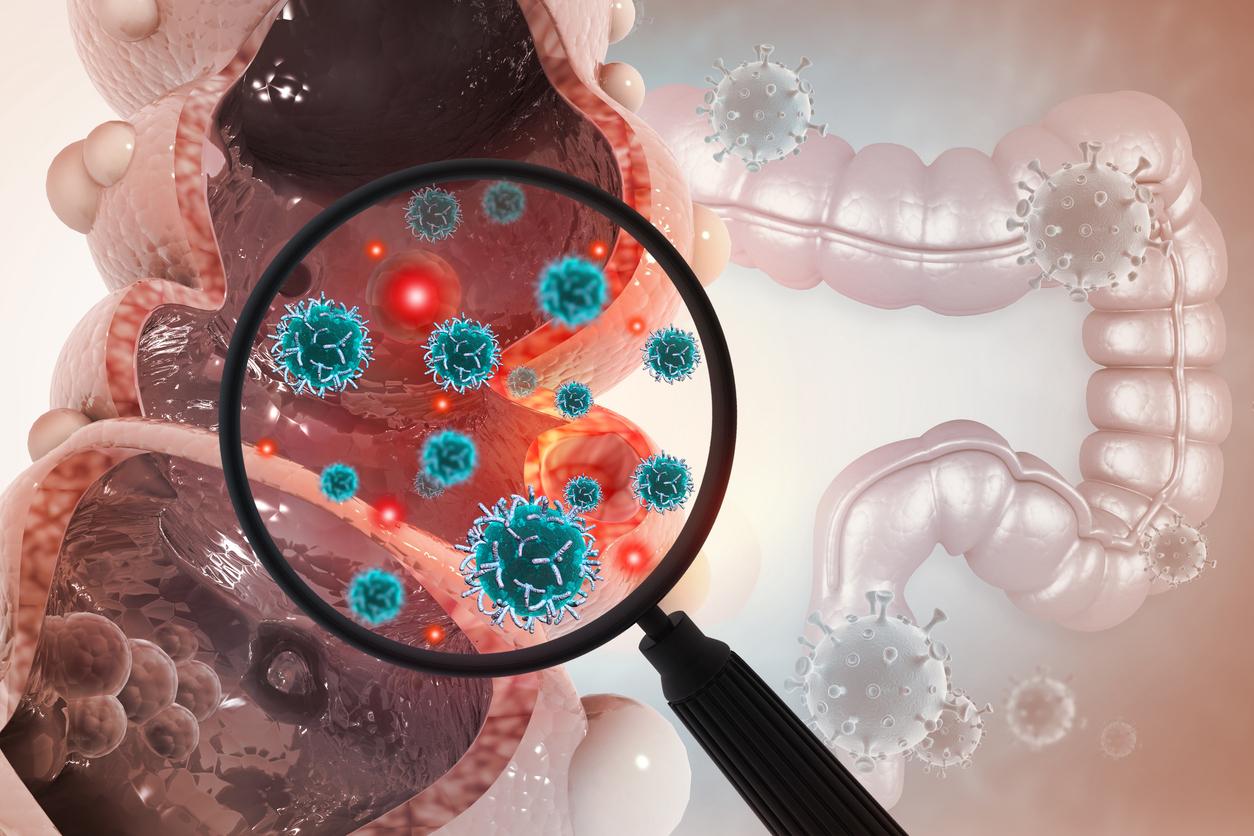

A team of Inserm researchers has highlighted how certain bacteria in the microbiota limit the action of chemotherapy against colorectal cancer.

- Colorectal cancers, among the most common in France with nearly 50,000 new cases each year, do not always respond well to conventional chemotherapy treatments.

- According to an Inserm study, certain bacteria in the microbiota, once infiltrated within a colorectal tumor, limit the action of chemotherapy against cancer.

- Infected cancer cells become less differentiated, therefore less visible to the patient’s anti-tumor immunity, and consequently less sensitive to the action of chemotherapy. A discovery that opens the way to potential new treatments.

Colorectal cancers, among the most common in France with nearly 50,000 new cases each year, do not always respond well to conventional chemotherapy treatments. This is particularly the case for cancers that affect the right segment of the colon.

A team of scientists from the National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm) has just highlighted the mechanisms involved in this chemoresistance. His work was published in the journal Gut Microbes.

The presence of E. coli bacteria in colorectal tumors

By analyzing the microenvironment of colorectal tumors from patients followed in hospitals in Créteil and Clermont-Ferrand, researchers were able to identify a strong presence of bacteria from the Escherichia coli family. Some of them produce an intestinal toxin, called colibactin, which is both genotoxic (i.e. responsible for damage to the DNA of their host’s cells) and protumoral. However, scientists have noted that the prognosis of the tumors analyzed depends precisely on the intratumoral presence of colibactin-producing E. coli bacteria (or CoPEc, their English acronym). The most threatening tumors were thus much more infiltrated by CoPEc than the others.

“But the distribution of these bacteria is not homogeneous within cancerous tissue”, explains researcher Mathias Chamaillard, who participated in the study. By analyzing metabolic and immune activity in the vicinity of bacteria, “it appeared that the tumor cells which are in contact with them do not have the same immunometabolic profile as those which are further away: they are much richer in glycerophospholipid droplets, compounds known to be immunosuppressive”, that is, reducing the activity of the immune system.

Cancer cells that become chemoresistant

But how could molecules that inhibit the activity of anti-tumor immunity promote resistance to chemotherapy? “The effectiveness [de la chimiothérapie] is mediated by our defense mechanisms: by killing cancer cells, chemotherapy causes the formation of cellular debris which is spotted by CD8 T lymphocytes. These immune cells then recruit other effectors to infiltrate the tumor together and reach tumor cells that have not necessarily been in contact with chemotherapy. This is the concept of immunogenic cell death.” According to the researchers’ observations, tissues rich in glycerophospholipids are less infiltrated by these lymphocytes than others.

Clearly, cancer cells infected by CoPEc become less differentiated, therefore less visible to the patient’s anti-tumor immunity, and consequently less sensitive to the action of chemotherapy. “Our results clarify how colibactin can promote chemoresistance, conclude the scientists. This paves the way for the development of new therapies to target the steps that allow lipid droplet accumulation and cell dedifferentiation.”