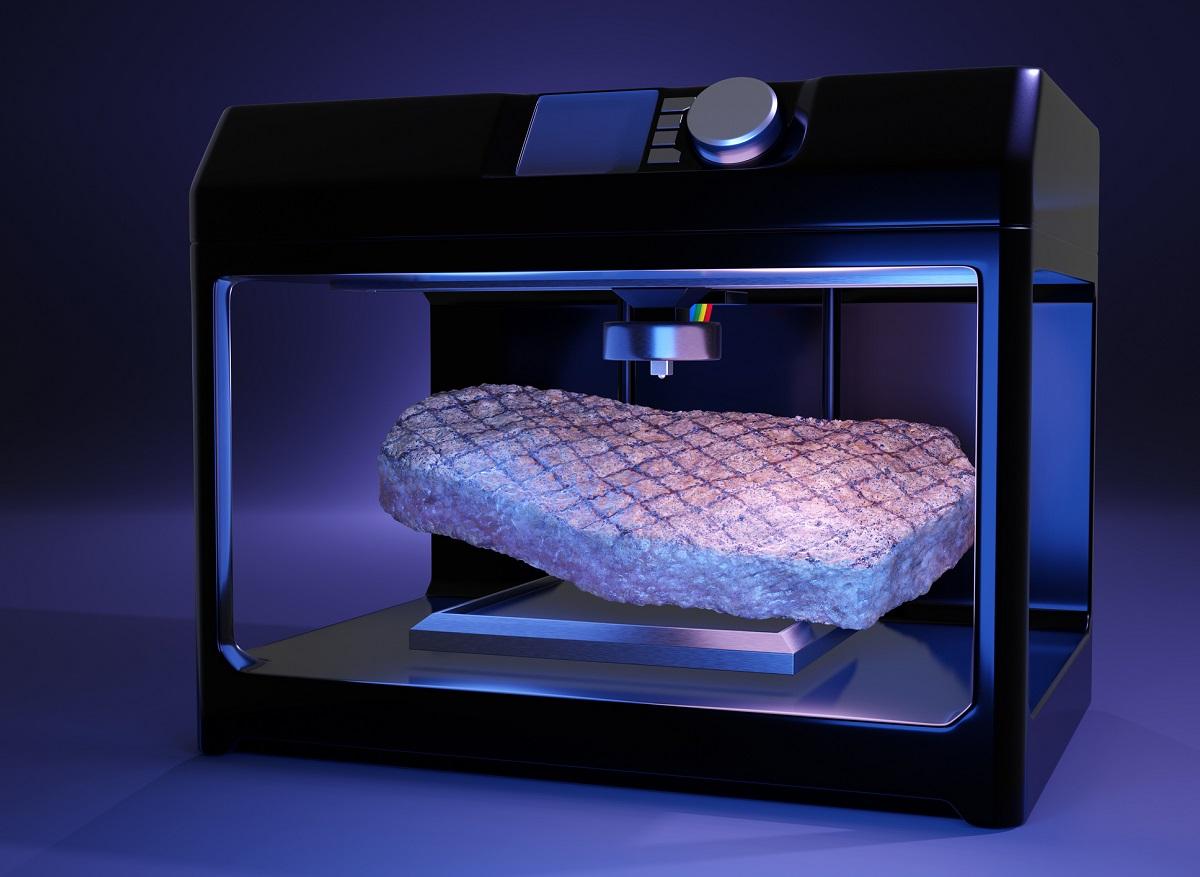

English researchers have succeeded in 3D printing bacteria-resistant parts. Ultimately, this could make it possible to make objects to fight infections in everyday life.

For years, 3D printing has been revolutionizing the field of health. It improves facial reconstruction and opens up many new possibilities in terms of grafts. Today, English researchers use it to fight against infectious diseases. According to their study published on January 21 in the journal Naturethey would have succeeded in developing bacteria-resistant 3D printable parts.

Researchers from the University of Sheffield in England used antimicrobial additives, small ingredients added to an object during its manufacturing process to prevent the growth of microbes, already on sale all over the world. In detail, they used a polyamide powder (PA12) in which they added an antibacterial compound based on silver. Using a 3D printer, the scientists then compared a part printed with conventional powder and another made from this mixture. They thus discovered that the parts containing the antimicrobial were more resistant to bacteria. They would be particularly effective against Gram positive (Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram negative (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) groups. These bacteria can lead to fatal diseases such as meningitis, pneumonia or sepsis.

Another interesting discovery: the 3D printed parts were not affected by the addition of the antibacterial compound and would retain the same properties as normal parts. They would therefore not be toxic to human cells. “The technical properties of the new composite are identical to those of the standard base material, polyamide 12. The composite is most effective in nutrient-poor hydrated environments and, in these circumstances, it is able to reduce the number of planktonic bacteria around of it and the number of bacteria in the biofilm attached to the surface”, note the researchers. This is because bacteria have trouble adhering to 3D printed parts, they noted.

Parts for hospitals or everyday consumption

Ultimately, this technological advance could make it possible to manufacture parts for hospitals subject to a lot of human contact by creating door handles for example. Oral health products such as dentures or everyday consumer items such as cell phone cases could also be made with these materials.

“Managing the spread of harmful bacteria, infections and growing antibiotic resistance is a global concern. Introducing antibacterial protection into products and devices at the time of their manufacture could be a critical tool in this fight. Most 3D printed products today do not have additional features. Adding antibacterial properties at the manufacturing stage will allow us to radically change the use of process capabilities”, explains Dr. Candice Majewski, lead of the project

“Our interactions with microbes are complex and contradictory – they are essential to our survival and they can kill us. Technology like this will be the key to informed and sustainable management of this crucial relationship with nature,” concludes Dr. Bob Turner of the University’s Computer Science Department.

The challenge of antibiotic resistance

These results are welcome at a time when bacteria are becoming more and more powerful. At the beginning of January, the World Health Organization warned of the growing antibiotic resistance of many pathogenic bacteria.

“This is one of the biggest health threats we have identified,” said Peter Beyer, from the WHO’s Department of Essential Medicines at a press briefing in Geneva, Switzerland. “We are seeing this spreading and we are running out of effective antibiotics against these resistant bacteria,” he explained. “Many initiatives are underway to reduce resistance, but we also need countries and the pharmaceutical industry to get more involved and provide sustainable funding and new innovative drugs,” said the director of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

According to a study published in November 2018 in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases33,000 people died in the European Union in 2015 because they did not receive effective antibiotic treatment against bacteria that had developed resistance.