Japanese researchers have developed an antibody to regrow teeth and are currently testing this potential new treatment on humans.

- In humans, teeth only grow twice.

- But researchers have created an antibody that can block the action of a protein called USAG-1 and thus allow teeth to grow.

- With this new treatment, it may be possible to control the location of a new tooth in the mouth.

Will we one day be able to do without implants and dentures? This is not impossible if we are to believe a team of Japanese researchers who have created an antibody capable of blocking the action of a protein called USAG-1 and thus allowing the growth of teeth.

An antibody to regrow teeth

In previous research, they tested this antibody on animals that had dental agenesis, which High Authority of Health (HAS) defines as “the absence of development of one or more dental germs”. Result: the antibody made it possible to regrow their teeth! Since this discovery, scientists have been carrying out clinical trials on humans to verify the safety of the drug, rather than its effectiveness. Currently, participants are healthy adults who have lost at least one existing tooth but do not have tooth agenesis.

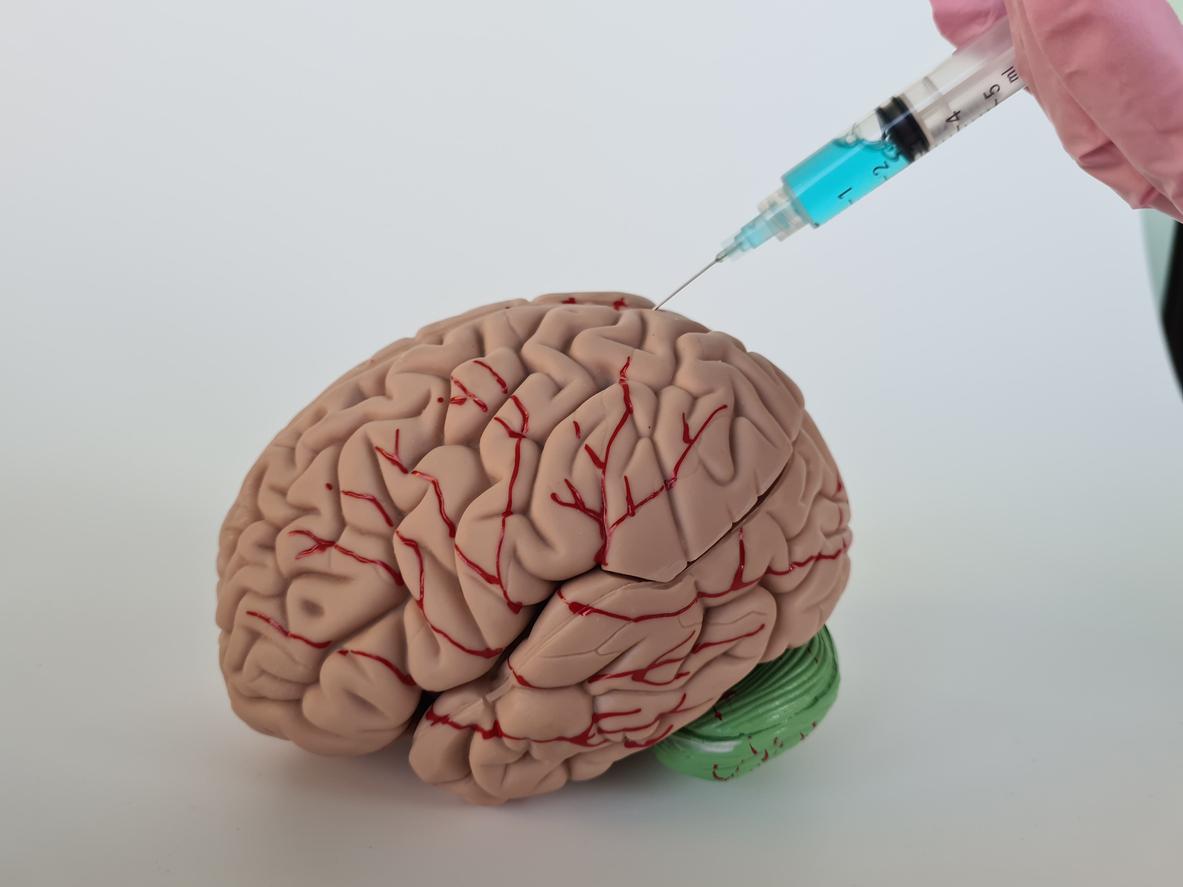

In humans, after the baby teeth, there are the permanent ones. We therefore only have two sets of teeth, unlike other animals, such as reptiles or fish, which regularly replace their fangs. “Restoring natural teeth undoubtedly has its advantages“, underlines Katsu Takahashi, one of the researchers, in a press release. According to him, with this new treatment, it could be possible to control the location of a new tooth in the mouth or even to locate it by the injection site of the medication.

A new treatment by 2030?

The research takes place in Japan, where 90% of people aged 75 or older in Japan have at least one missing tooth. “It is highly expected that our technology can directly extend their healthy life expectancy“, concludes Katsu Takahashi.

But the scope of this new treatment could be much greater. In a press releasethe HAS cites a percentage from the World Health Organization (WHO): by 2030, complete edentulism would affect approximately 30% of the world population… The year that Japanese researchers are targeting as the year of marketing of their new treatment.