According to a new study from MIT, the structure of the coronavirus responsible for Covid-19 could be vulnerable to ultrasonic vibrations, in the frequencies used by medical imaging.

- The modeling developed by the MIT team shows that 100 MHz ultrasonic vibrations can deform the shell of the coronavirus.

- Lower frequencies, between 25 and 50 MHz, are even more effective at deforming and fracturing the envelope of the coronavirus.

- Ultimately, ultrasound could be considered as a therapeutic avenue against SARS-CoV-2.

Breaking the “shell” of SARS-CoV-2 by causing it to collapse on itself may be possible. This good news is the subject of a short story led by researchers from the Mechanical Engineering Department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and published in the Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids.

Its authors studied the structure of the coronavirus, with its spike-like proteins that latch onto healthy host cells and trigger viral RNA invasion. They were able to demonstrate that it was possible to damage this structure using ultrasound between 25 and 100 megahertz, the frequency used for medical imaging.

Using computer simulations, the research team modeled the mechanical response of the virus to vibrations in a range of ultrasonic frequencies. The vibrations between 25 and 100 megahertz thus trigger the collapse of the envelope and the tips of the virus, which began to break in a fraction of a millisecond, whether the simulation takes place in the air or in the water.

“We have proven that under ultrasound excitation, the envelope and tips of the coronavirus vibrate, and that the amplitude of this vibration is very large, producing strains that could break up parts of the virus, causing visible damage to the outer shell and possibly invisible damage to the RNA inside”says Professor Tomasz Wierzbicki of MIT, who hopes that these results will launch “a discussion between various disciplines”.

A deformation of the virus shell under the intensity of ultrasound

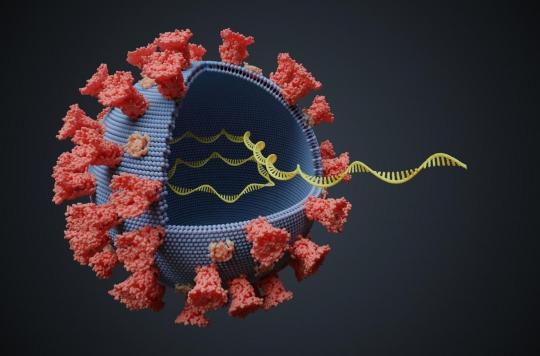

The researchers used previous work to establish the general structure of the coronavirus: it includes a smooth envelope of lipid proteins and peplomers, which are the very dense, spike-shaped receptors that protrude from the envelope.

With this geometry in mind, the team modeled the virus as a thin, elastic envelope covered in about a hundred elastic spikes. They then introduced ultrasound into the simulations, and observed how the vibrations propagated through the structure of the virus. They started with vibrations of 100 megahertz, or 100 million cycles per second, which she estimated to be the natural vibrational frequency of the shell, based on what is known of the physical properties of the virus.

When they exposed the virus to these 100 MHz ultrasonic vibrations, the natural vibrations of the virus were then undetectable. But within a fraction of a millisecond, the external vibrations, which resonated with the frequency of the virus’ natural oscillations, caused the shell and spikes to deform inward, similar to a ball bouncing on the ground.

As the researchers increased the intensity of the vibrations, they saw the virus shell fracture. At lower frequencies of 25 MHz and 50 MHz, the virus deformed and fractured even faster, both in simulated air and water environments, which are similar in density to body fluids. . According to Professor Wierzbicki, “these frequencies and intensities are within the range of those safely used for medical imaging”.

Now researchers are working with microbiologists using atomic microscopy to observe the effects of ultrasonic vibrations on a type of coronavirus. If it is proven that ultrasound does indeed damage coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, they may consider ultrasound to cure the infection.

.