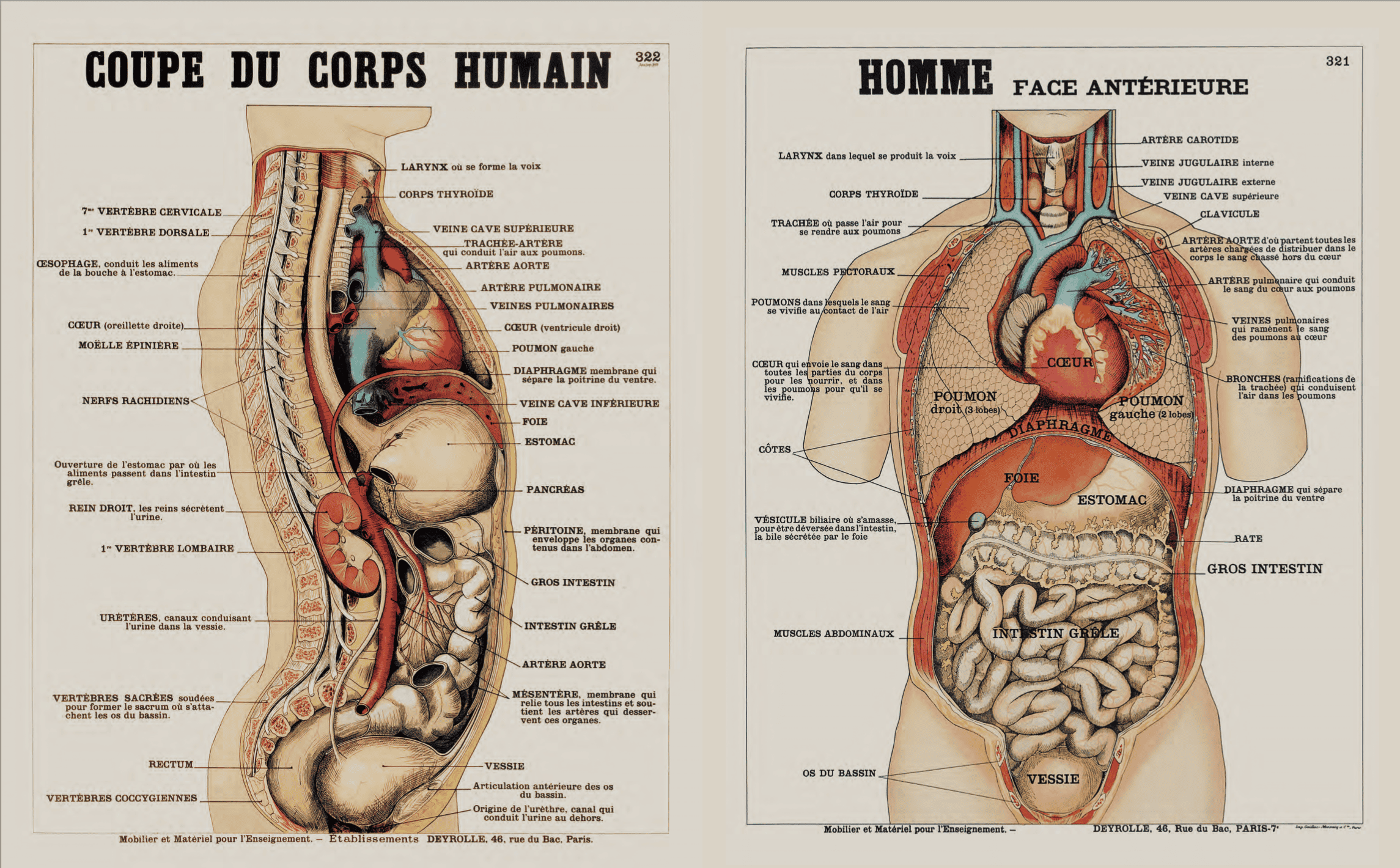

A historical commission sent to the University of Strasbourg has found human remains in connection with the experiments of Prof. Hirt, a Nazi doctor.

The University of Strasbourg is finally opening its eyes to its history, and to the abuses that took place in its premises during the Second World War. She appointed an independent historical commission to investigate the actions of Prof. August Hirt, a German anatomist from the Ahnenerbe Institute of Racial Anthropology, who carried out experiments on victims of the Holocaust.

She is particularly looking for human remains from Jewish victims in the anatomical collections of the university. Research has already led to the discovery of around twenty jars bearing Professor Hirt’s name, as well as 160 medical theses written between 1943 and 1944, which had until then gone unnoticed.

“A university that has committed crimes”

There is no proof for the moment that these remains come from Jewish victims of the concentration camps, but this find lays the first stone of a historical reconstruction, according to Mathieu Schneider, the vice-president of the University of Strasbourg, whose the comments were reported by France Blue. “Unfortunately we had to house within our walls a university which committed crimes. It is this story that we must write ”.

“The first work of the historical commission clearly shows that there was an intensification of research between 1943 and 1944 and that this research was clearly intended to serve the racial theses and medical experiments of Nazism”, he said. notably explained.

Historical reports state that 86 people were deported from the Auschwitz camp to be gassed at the Alsatian concentration camp at Struthof – the only camp built on French soil. Their remains were then dissected at the University of Strasbourg by Prof. Hirt and his team, for research purposes and to build a collection of skeletons.

Sensitive subject

The remains of these experiences were indeed found by the Allies after liberation, and buried in a Jewish cemetery in Strasbourg. But rumors suggesting some of the remains were not found swirled the halls of the university, creating a point of tension among researchers and staff.

The discovery in 2015 of fragments of skin and organs of a German detainee, Menachem Taffel, identified thanks to his deportee’s tattoo, had already fueled the debate revived by Dr Michel Cymes a few months earlier. The doctor-television host had indeed mentioned the existence of these remains in his book, Hippocrates in the Underworld.

Putting the puzzle together

Faced with the multiple jars of formalin and slides that support the shelves of anatomy laboratories, the work of the investigators of the historical commission is colossal, estimates Christian Bonah, professor of history of science at the University of Strasbourg. “These are thousands of objects that must be identified and inventoried,” he explains. You have to understand where they are coming from and whether they are linked to criminal activity. “

An indispensable task for history and for science. “We need to piece together the pieces of the puzzle,” adds Mathieu Schneider. And from there, present a cohesive narrative, which we can embrace. We will thus be able to build a reflection on the ethics of medicine for our students. “

A flouted ethics, in which the moral entity of the University of Strasbourg would not have participated. From 1939, and until the Liberation, the students and their teachers had moved to Clermont-Ferrand.

.