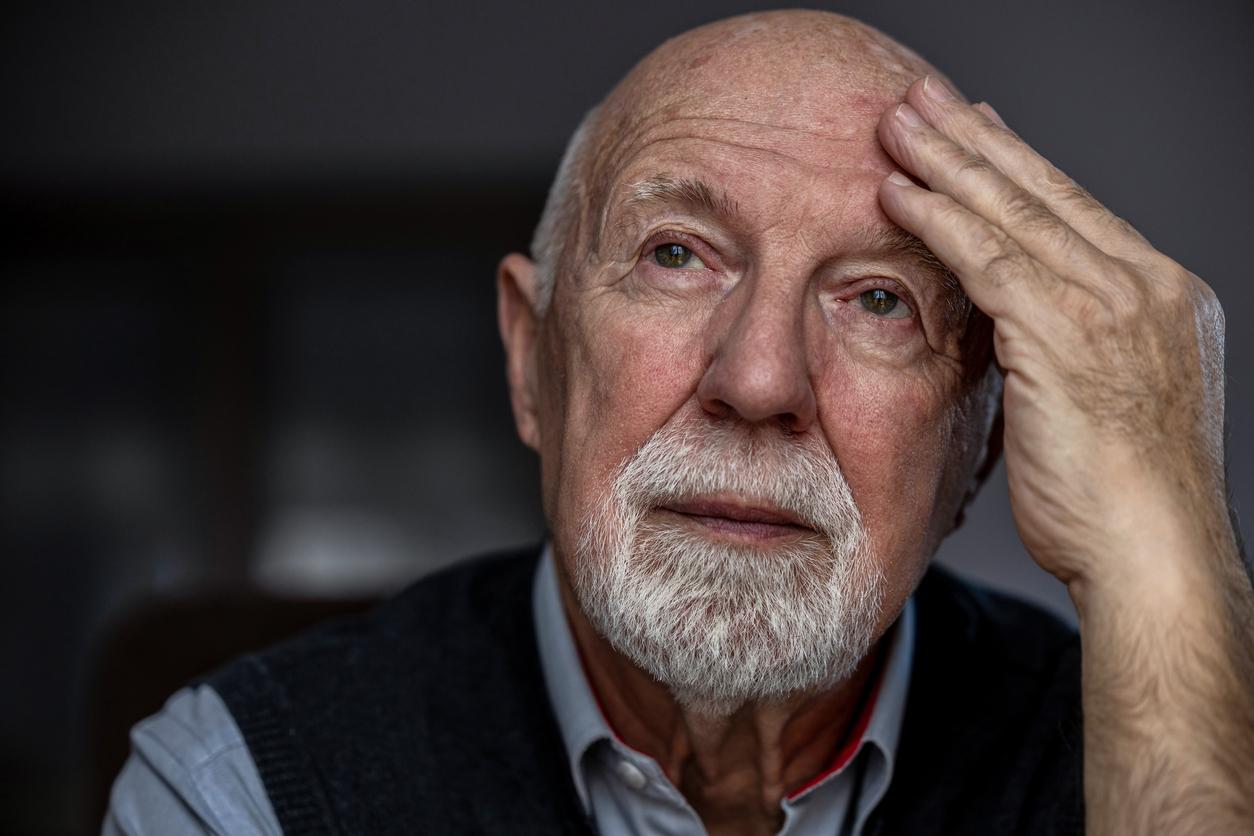

In areas where more than one language is spoken, the prevalence of dementia is 50% lower than in areas where the population uses only one language to communicate.

- Actively speaking two languages can delay the onset of symptoms of mild cognitive decline, which often heralds Alzheimer’s disease.

- Moreover, people practicing active bilingualism were diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment later than those who were passively bilingual, that is, speaking only one language but passively exposed to another.

Mastering several languages is not only a great opportunity to open up to other cultures and to forge one’s curiosity and open-mindedness. It is also a way to guard against cognitive decline associated with aging.

This is the conclusion reached by a team of researchers from the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC) and the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF), in Spain. In a study published in the journal Neuropsychologythey explain that regularly speaking two languages—and doing so for a lifetime—boosts cognitive reserve and delays the onset of symptoms associated with cognitive decline and dementia.

“The prevalence of dementia in countries where more than one language is spoken is 50% lower than in regions where people only use one language to communicate”details Professor Marco Calabria, from the Faculty of Health Sciences at UOC and a member of the NeuroLab research group.

A neuroprotective effect

Previous work had already shown that speaking two or more languages throughout one’s life increased one’s cognitive faculties and delayed the onset of dementia. This new study goes further. “We wanted to find out the mechanism by which bilingualism contributes to cognitive reserve in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, and whether there were differences in terms of the benefit derived from different degrees of bilingualism, and not only between monolingual and bilingual people”explains Professor Calabria, who led the study.

Therefore, the researchers established a gradation in bilingualism: from people who only speak one language but are passively exposed to another, to people who have an excellent command of both and use them without discrimination on a daily basis.

They then focused on the population of the city of Barcelona, where the use of Catalan and Spanish is very variable, with some neighborhoods being predominantly Catalan-speaking and others where Spanish is the main language. “We wanted to take advantage of this variability, and instead of comparing monolingual and bilingual people, we investigated whether in Barcelona — where everyone is more or less bilingual — there was some degree of bilingualism that had neuroprotective benefits. “explains Professor Calabria.

Sixty-three healthy people were recruited, as well as 135 patients with mild cognitive impairment and 68 people with Alzheimer’s disease. All the volunteers completed a questionnaire to establish their skills in Catalan and Spanish, and to check their level of bilingualism. The results were then compared with age at neurological diagnosis and symptom onset, and asked participants to perform various cognitive tasks, including memory tests.

It was found that “people with a higher degree of bilingualism were diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment later than those who were passively bilingual”, notes Professor Calabria. According to him, speaking two languages and regularly switching from one to the other is a linguistic gymnastics beneficial for the brain. This reinforces executive control, which in particular makes it possible to perform several actions at the same time.

A preacher of the onset of Alzheimer’s

For the research team, this is an important finding because, “in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, this system could compensate for the symptoms. So when something doesn’t work well because of illness, thanks to being bilingual, the brain has effective alternative systems to solve the problem”. Scientists also believe that “active bilingualism is an important predictor of delayed onset of symptoms of mild cognitive impairment—a preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease—because it contributes to cognitive reserve.”

Researchers are now continuing their work to determine whether bilingualism is also beneficial for other neurological pathologies, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases.

.