This Friday, June 19th is World Sickle Cell Day. Jacques Elion, teacher-researcher at Inserm, has devoted his research work to this disease and gives us an update on existing treatments, where bone marrow transplantation and gene therapy bring hope.

There is currently no widely available cure for sickle cell disease. For the past ten years, this genetic disease has aroused more and more interest on the part of major pharmaceutical groups and States. Research is advancing and more and more bone marrow transplants are making it possible to treat patients. At the same time, gene therapy is being tested and is showing promising results. Jacques Elion, researcher at Inserm and consultant at the National Institute of Blood Transfusion, takes stock of the treatments available.

Sickle cell disease is the first genetic disease in France but still remains relatively unknown. How do we explain it?

Sickle cell disease is little known because it is insufficiently taught in medical universities and general practitioners are rarely confronted with this disease. It is less known than other genetic diseases because it is less publicized than the others. This is explained by the fact that there are multiple patient associations which are dispersed and which have never managed to federate. However, this dynamic is changing. In recent years, we have observed worldwide that organizations are trying to come together to share more information about the disease, to ensure that it is better taught and to put pressure on decision-makers to improve its management. charged. There has been an effort by governments over the past ten years with a rare disease plan that takes care of patients from birth until death with the development of care protocols for practitioners. They have also facilitated access to clear lists of specialists and specialized centers to improve the patient journey.

How is patient care going?

Treatment should be done as soon as possible. If possible, it should take place before the newborn is three months old, although the first complications due to the disease usually occur after 6 months. Patients then undergo preventive medicine in order to anticipate possible infections and this is done by prescribing Oracillin, an antibiotic. These children are given additional vaccines to those provided by the international vaccination program. Then, it is necessary to do education and train the parents, in particular to feel the spleen which is often very affected by the disease and where it can have deep anemia with hemoglobin figures which drop drastically. They are taught the signs of complications, such as fever which is not managed in the same way in subjects with sickle cell disease.

When the patient is older, complications can occur and lead to a transfusion. For children and young adults who have repeated painful attacks, they are prescribed hydroxycarbamide to reduce the occurrence of these attacks and improve their quality of life. This drug works fairly well in children, but some adults do not respond to these treatments, hence the interest in developing new drugs.

Are there curative treatments?

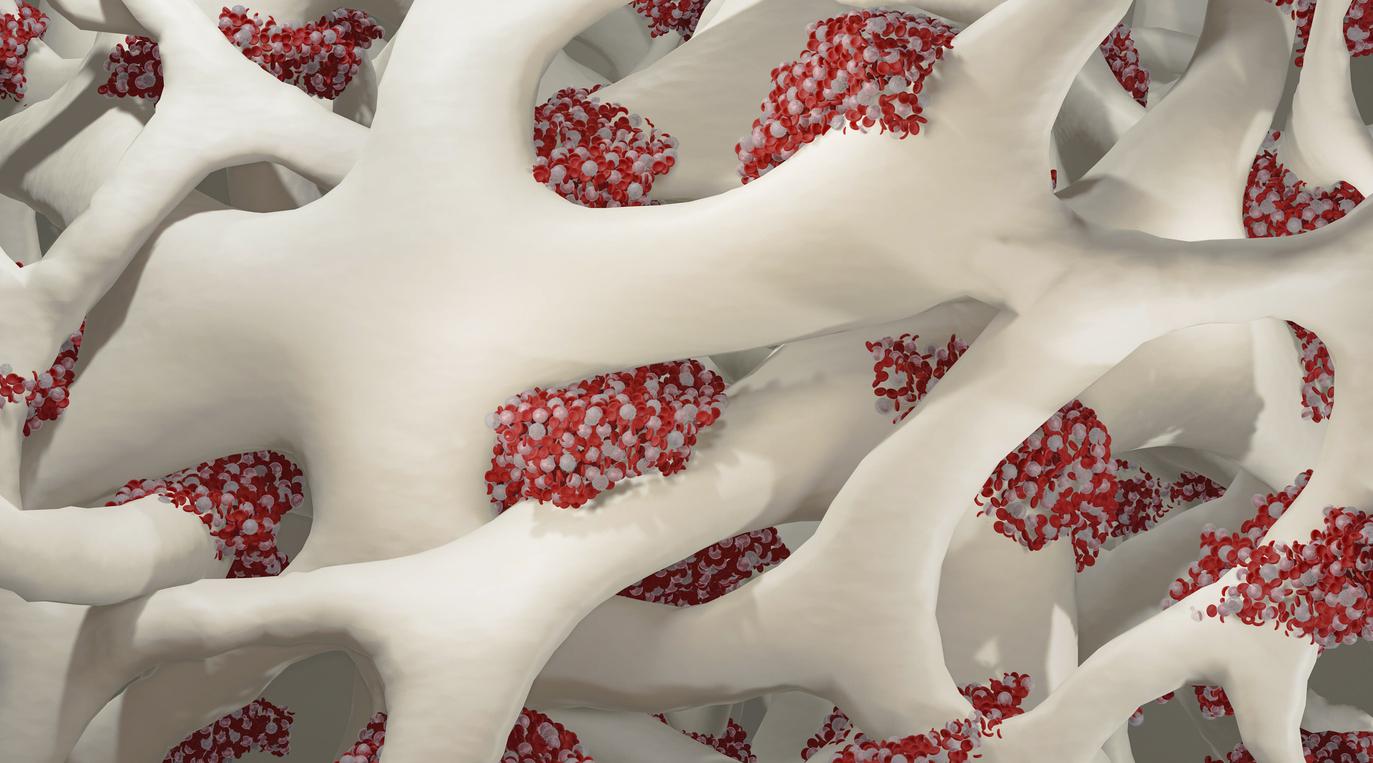

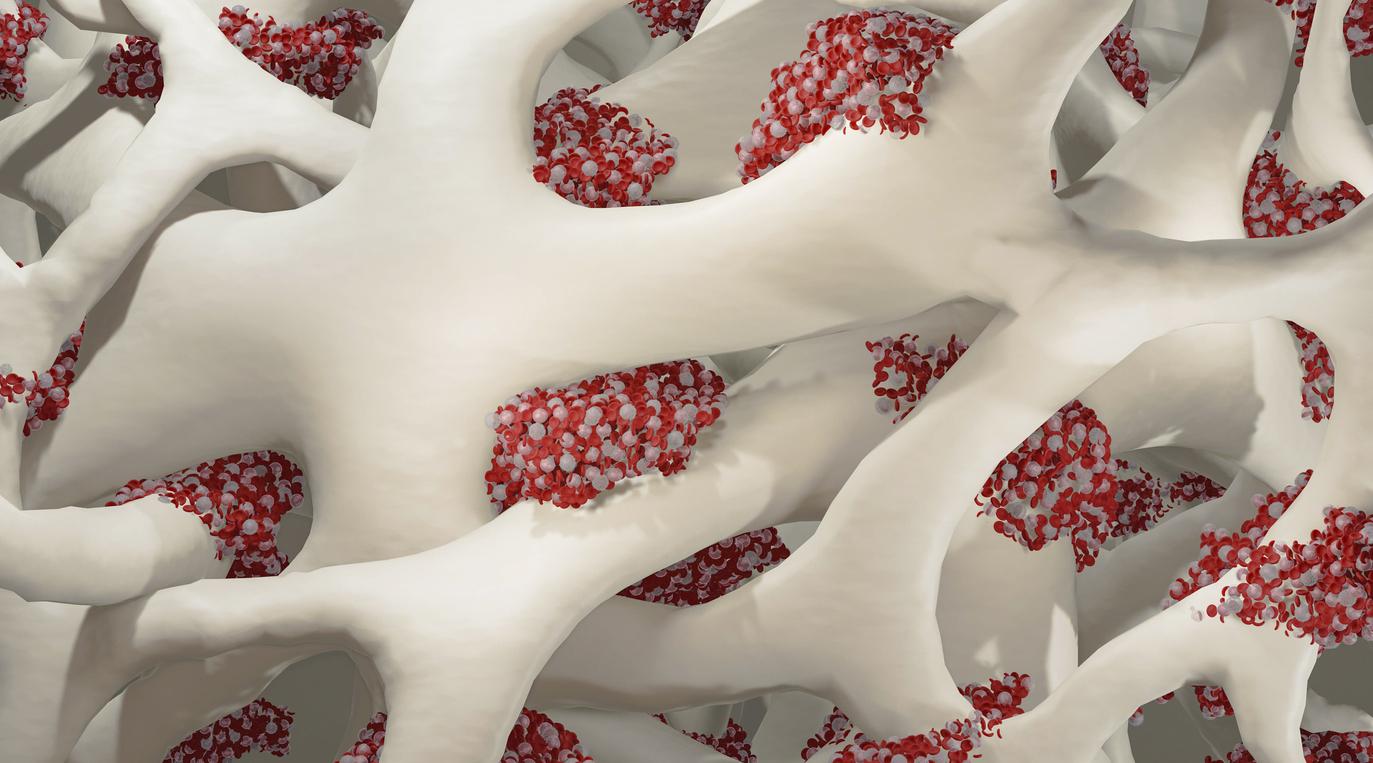

Bone marrow transplantation is the most developed curative approach. Currently, it is only available for donors from the same family, mainly the brother or the sister, who must be compatible. This treatment is expensive, around €70,000, but it is effective and presents very few complications. Transplants are only performed in patients who have severe forms of the disease and this is done almost exclusively in children, but sometimes it can also affect young adults. This procedure is not insignificant and for all the patients whose doctor mentions the transplant, a jury of experts meets and studies their file. Doctors will then destroy the patient’s bone marrow with chemotherapy, to replace it with stem cells from the donor. For a period of between 2 and 4 weeks, the recipient patient is very vulnerable and must remain in a sterilized room, then, little by little, the stem cells are re-implanted in the marrow and the patient begins to make blood cells again.

The other curative technique explored is gene therapy. This technique consists in taking the cells of the sick patient and bringing in a normal globin gene, beta A. This is similar to molecular transplantation, and thanks to modern genome editing techniques, we are able to go to correct the mutation, or even to act in more specific places of the genome which regulate the expression of adult hemoglobin. Gene therapy has entered the concrete in recent years with around twenty patients treated worldwide. This technique remains experimental, and doctors must be certain that it does not present any long-term complications.

Can we imagine being able to treat patients with this disease in the future?

In poor countries, emphasis must be placed on neonatal screening and making it compulsory everywhere, especially in Africa. This is progressing in certain capitals but no country on the continent manages to impose it on its entire territory. I have a colleague, Chérif Rahimy, who works in Cotonou, Benin. In his center, he imposes the screening of newborns and identifies those with sickle cell disease. Thus, he can start a treatment, increase the number of vaccines to protect populations from infections or even make food better. The survival rate of these young children at 5 years is 10 times higher than the general population.

In richer countries, especially in Europe and the United States, the interest of ‘big pharma’ is growing and this is leading to creating hope for patients and activating research. Patient associations are also more vocal and a global association has been created, ‘Global loans of sickle cells disease’, to put more pressure on public authorities and raise awareness of sickle cell disease.

.