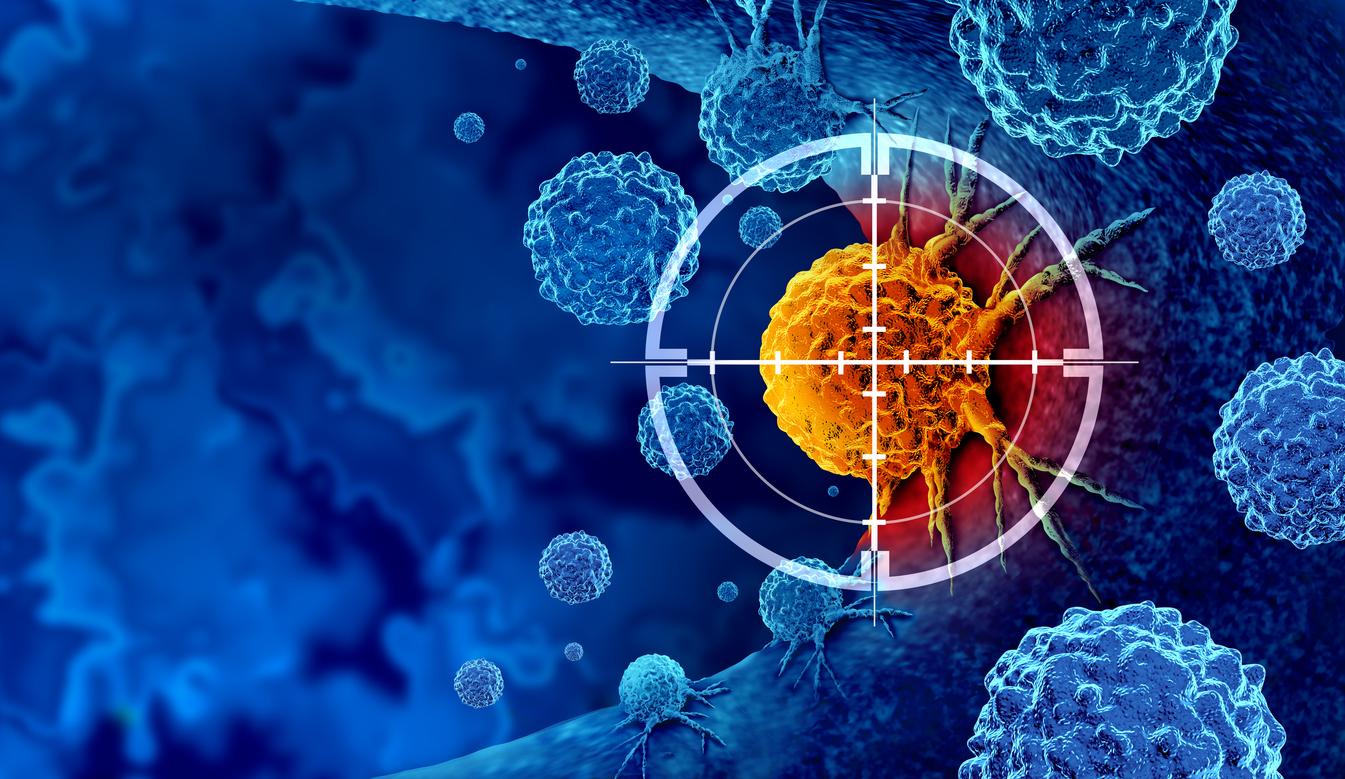

Laboratory tests on a substance contained in green sponges from the North Pacific have shown promising results.

At first glance, this sponge is nothing exceptional. Green, clinging to its rock and hidden at the bottom of the North Pacific Ocean, Latrunculia austini could have gone unnoticed. It would have been a mistake. According to a team from the Medical University of South Carolina (United States), this aquatic animal harbors chemical compounds with anticancer properties.

The Alaskan green sponge has long remained unknown to humans. It was only discovered ten years ago, during an initiative of the United States Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA). In 2005, its Alaska Fisheries Science Center launched an inventory of the waters surrounding the American state.

A promising molecule

It is during this work that Latrunculia austini was met for the first time. And scientists were quick to pay it special attention. Unable to flee or defend themselves, marine sponges secrete chemicals that protect them from predators and extreme conditions.

And some of these molecules may well be of interest to our species. One in particular, which belongs to the family of discorhabdins. University researchers found that the structure of the molecules did not match any found on land or in tropical marine environments.

In the laboratory, this form of discorhabdin has been exposed to tumor cells from a patient’s pancreas. The chemical then revealed marked anti-cancer activity, going so far as to destroy certain cells.

“On average, less than 1% of the sponge extracts will have an anticancer activity comparable to that observed with the green sponge, underlines Fred Valeriote, who carried out the research in the laboratory. This is a promising, but preliminary, breakthrough in the development of new treatments for pancreatic cancer. “

Very low survival

The man behind the discovery of the Alaskan green sponge is more enthusiastic. “You wouldn’t think, seeing this sponge, that it was a miracle sponge; but it may well be, ”says Bob Stone.

But long years of development will be necessary before arriving at a drug. A more stable synthetic formulation will have to be found before testing it in animals or humans.

The promise remains exciting: pancreatic cancer progresses slowly, which reduces the effectiveness of chemotherapy. It is also known for its very high death rate. 5 years after diagnosis, only 9% of patients are still alive.

.