What are the manifestations, causes, difficulties and support needs related to dyslexia? With Rose-Marie Lirola, speech therapist in charge of teaching at the Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris, Why Doctor takes stock of this disorder which would concern 4 to 5% of students in an age group… but also many adults whose difficulties were much less taken care of as children than they are today.

– How many people, children or adults, are affected by this problem?

Rose-Marie Lirola – It is estimated that between 5 and 15% of school-age children are affected. This prevalence is for the world and includes the domains of reading/writing and mathematics, so not just dyslexia –in France this disorder would concern 4 to 5% of pupils in an age group, Editor’s note- . These figures which vary a lot according to the languages and the cultures since it depends on the degree of “opacity” of the language. In some languages, each letter represents one and only one sound, while in other languages (like French), a letter can have different pronunciations. For example, in French, the “c” can be pronounced “k” or “ss”. In Polish, unlike French, each letter has its own sound, which simplifies learning to read but complicates the detection of dyslexia.

As far as adults are concerned, the figures are again very imprecise because screening for dyslexia is quite recent. Adult patients who were not diagnosed as children have, for probably social reasons, difficulty in mentioning their difficulties and are not “counted” as dyslexic.

– But exactly what are the symptoms of dyslexia?

RM. I. – It is a persistent, lasting difficulty in associating a sound (phoneme) with a letter (grapheme) which leads to difficulties in decoding. People with dyslexia have difficulty with accurate and fluent word recognition, slow reading, choppy decoding. Most of the time, people with dyslexia have an associated dysorthography, that is to say, difficulties in learning the spelling of words and in remembering them for a long time. You should know that today we speak less of dyslexia, dysorthographia or dyscalculia but rather of “specific learning disorders with deficit in reading and/or written expression and/or calculation”.

– And what are the causes?

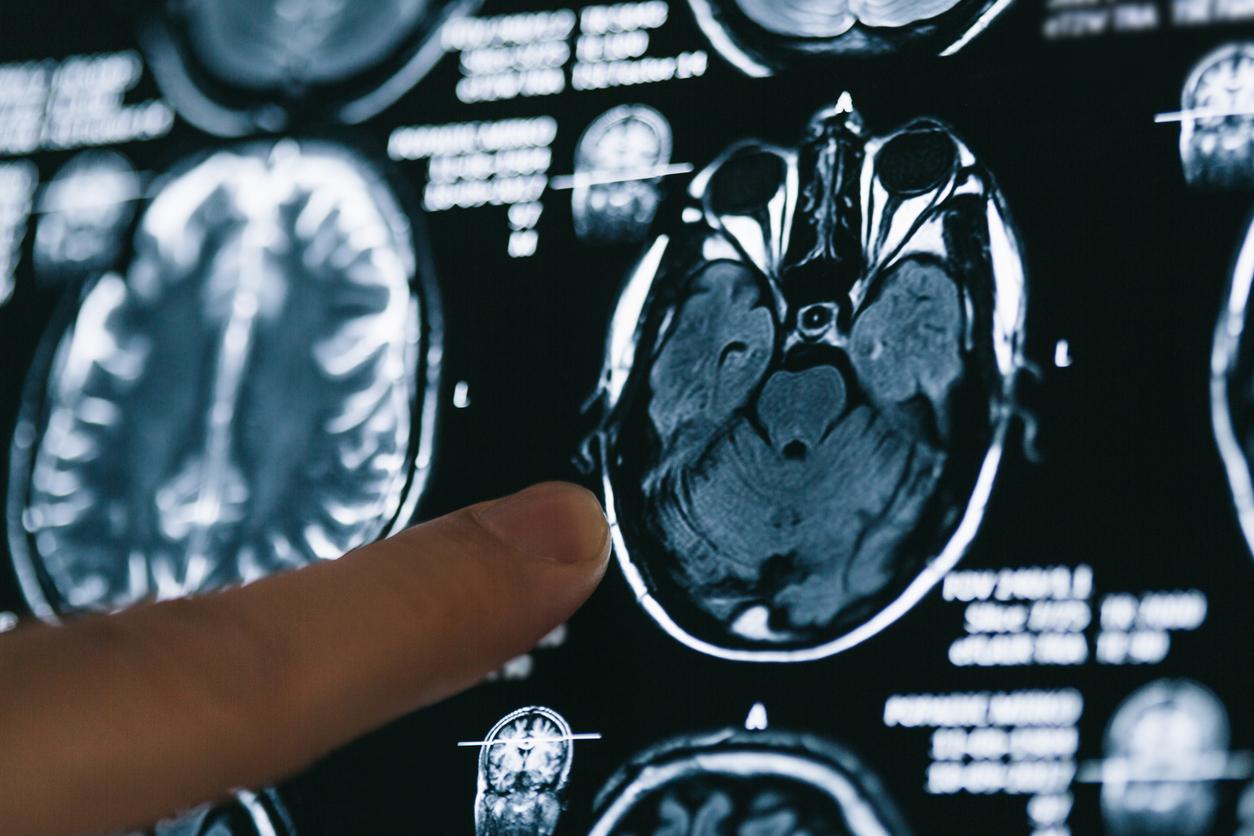

RM. I. – Dyslexia is a neurodevelopmental disorder linked to the dysfunction of what is called the “visual word form area”, a part of the brain located on the left of the head, behind the ear. It is thought that this dysfunction is due, at the embryonic stage, to a particular migration of cells in the neural tube when the two hemispheres of the brain are formed, perhaps linked to environmental factors. On the other hand, there are also genetic causes for dyslexia, a high rate linked to heredity, but we now know that if we train or re-educate children with dyslexia, this can modify their nervous system. at the molecular level and increase the chance that their offspring will have less severe dyslexia.

To illustrate what dyslexia represents, we can say that it is like the link between a switch and a lamp: the switch is the letter, the lamp is the way this letter is pronounced and the problem c is the electric wire that represents the work of the brain during reading, it is as if the network were slowed down.

– Can we speak of a disease?

RM. I. – It’s up to the patients to say so! Above all, it should be noted that many have incredible skills in other areas, drawing, three-dimensional conceptualization, a very fine perception of details and great emotional intelligence. People who suffer from dyslexia are often very human people.

– Beyond the classic symptoms, what other disorders can dyslexic patients experience?

RM. I. – They often encounter problems in the execution of certain tasks, for children for example, preparing a school bag without forgetting books, notebooks, glasses… Among students, we sometimes observe avoidance of activities that require school or university skills, difficulties integrating changes into their schedule, meeting appointment times by being either late or too early.

– Can dyslexia be cured?

RM. I. – No, just as you will have blue or brown eyes all your life, the dyslexic person will always have a residual slowness when reading texts, even if they will read almost normally. But I want to emphasize that it’s a decoding problem, not a comprehension problem: there are children who decode very well but who don’t understand what they’re reading, and that’s not dyslexia!

– Who makes the diagnosis of dyslexia?

RM. I. – It is the speech therapist, based on well-defined criteria. This is done through a consultation that begins with a clinical interview that allows you to identify possible sight and hearing problems, to see if there is a family history and when and how the difficulties began. For adults, this clinical interview is very important to review the difficulties encountered during childhood.

This first part of the consultation is what will put us on the track. Then there is a series of tests that allow to evaluate various criteria and establish a standard deviation from the mean. If this difference is below a certain threshold then there is a pathology.

– And then, how is the treatment going?

RM. I. – Based on the diagnosis, which is used to assess the seriousness of the problem, the care protocol is defined, which is different depending on the case. The literature provides for a treatment of 20 minutes 5 days a week… We cannot keep up with this rhythm in reality! For my part, I propose two sessions per week. With family involvement. But this point is debated… As far as I am concerned, for child patients, I consider that this parental involvement, beyond the fact that it allows certain exercises to be continued at home, brings real awareness and facilitates monitoring of progress.

– But concretely, what are the exercises practiced during these sessions?

RM. I. – There is no consensus on this point either. First, the most accepted theory is to distinguish three types of dyslexia, phonological dyslexia, visuo-attentional dyslexia and that which is mixed. Some authors even speak of 18 different types, including those related to visual disorders, but we are not here to debate them… For phonological dyslexia, for example, I have my patients work on sound processing (phonology). You should know that a dyslexic person hears all the variations of sounds: when you pronounce the sound “p” several times, the patient can hear all the possible variations of this sound; how do you expect him to spell the letter correctly since he heard different sounds each time you said the word? So I work a lot on words to be cut into syllables to analyze the macrostructure, then finer work on the words in which to manipulate the phonemes. This always with a passage in writing and with very simple words at the start and of increasing complexity.

For visuo-attentional dyslexia, there would be a disturbance in the number of letters that can be processed/seen simultaneously in a multi-letter sequence. The exercises, which have been scientifically validated, take place in close partnership with the family because it is an intensive program (6 days a week, 20 minutes a day) with visual search and discrimination exercises ( find the same form among distractors…), visual correspondence tasks (similarity or not between two forms, letters…), and finally, visual analysis tasks (find words among others).

These exercises are administered in a very specific order first on non-verbal material (drawings, shapes, symbols) then verbal (letters). Gradually, the principle consists in training the child to see the groupings of letters and not to focus on single stimuli (letters).

– Are there currently advances in the management of dyslexia?

RM. I. – I would like ! In fact, yes, there are novelties. In particular vision-related devices that play on the visual afterglow effect. Some patients feel improvements, others do not, but it will be necessary to determine what part of the devices in the progress they are making and, above all, it will be necessary to carry out scientific studies to see if it really works.

.