When they return from a past trip to the other side of the world, many international travelers carry in their intestines potentially deadly new strains of superbugs, thus promoting their spread.

- International travel promotes the spread and mutation of microbial resistant bacteria, which lodge in the gut microbiome of tourists.

- By analyzing fecal samples from tourists after international travel, researchers discovered 56 unique antimicrobial resistance genes, including some that were colistin-resistant to last-resort treatments for infections caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria.

Going to explore a country on the other side of the planet, then returning home, contributes to antibiotic resistance and the spread of these “superbugs”, which even the most powerful antimicrobials are not always able to eliminate.

This is the conclusion reached by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis. In a study published in the journal GenomeMedicinethey explain that the gut microbiome of international travelers is the perfect place for potentially deadly, antibiotic-resistant new bacterial strains to grow.

“Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, we knew that international travel was contributing to the rapid increase and spread of antimicrobial resistance around the world, explains Alaric D’Souza, co-lead author of the study. But what’s new here is that we found many entirely new genes associated with antimicrobial resistance, suggesting a worrying problem on the horizon.”

New resistance genes detected in travelers

Poverty, poor sanitation and changing agricultural practices have turned many low-income developing regions into hotbeds of bacteria-borne diseases, including infections that are increasingly resistant to a range of antibiotic treatments. .

Similarly, high population densities facilitate the transmission of these bacteria between community residents and travelers through exposure to contaminated drinking water and food, or to restrooms, restaurants, bedrooms, etc. poorly sanitized hotel and public transport. Returning home, travelers run the risk of transmitting these new bacteria to family, friends and other residents of the community.

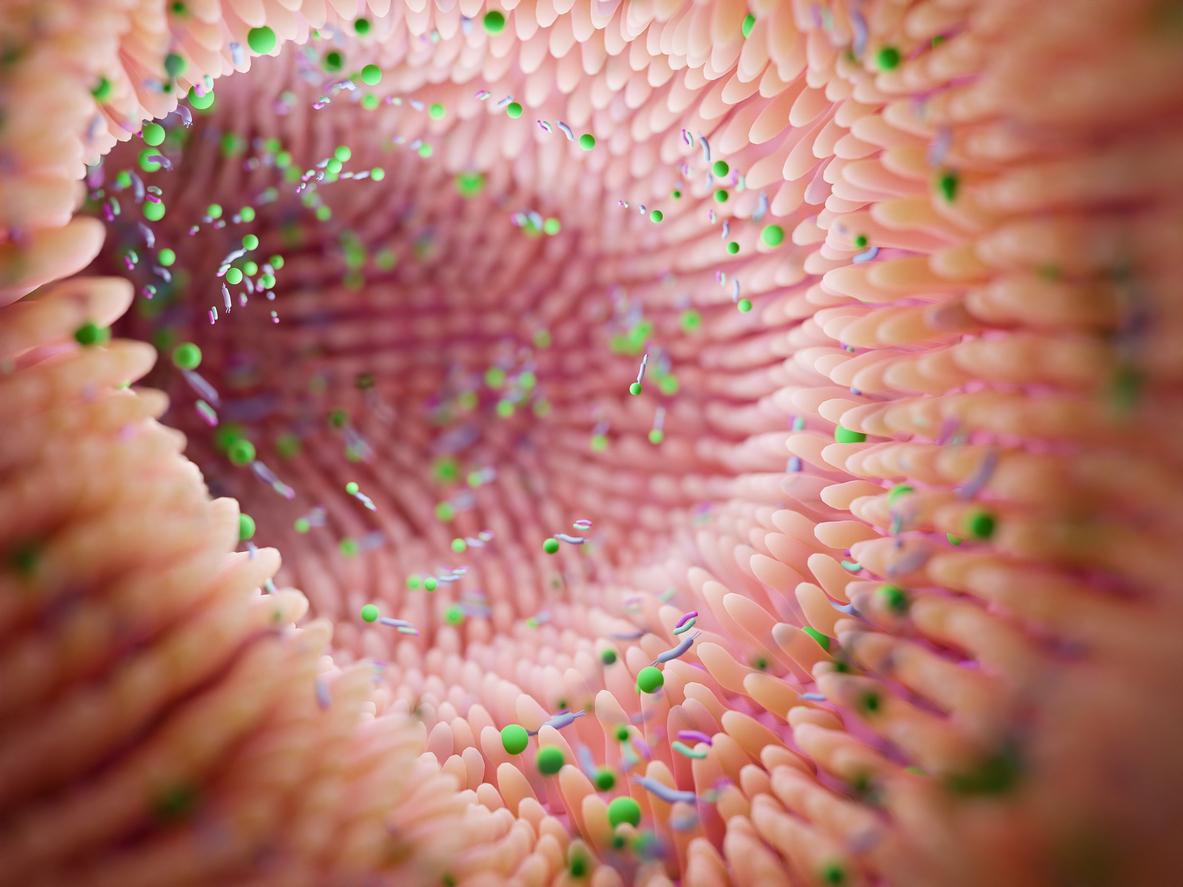

Researchers in the present study analyzed bacterial communities in the gut microbiomes of 190 Dutch adults before and after travel to one of four international regions with high prevalence of resistance genes: Southeast Asia, South Asia, South, North Africa and East Africa. They also analyzed faecal samples as part of a larger multi-centre survey of around 2,000 Dutch travellers, the majority of whom were tourists.

They then found that after their travels, the tourists all showed an increase and an abundance of bacteria endemic to the regions visited. All of these bacteria carried antimicrobial resistance genes.

To achieve this result, they used a technique called metagenomic sequencing which makes it possible to identify all the organisms present in a given sample: the good bacteria, the dangerous bacteria and even those which are completely new. A total of 121 antimicrobial resistance genes were detected in the gut microbiome of the 190 Dutch travellers.

The study results also confirmed that 56 unique antimicrobial resistance genes had become embedded in the gut microbiomes of travelers during their trips abroad. Among them are several high-risk mobile resistance genes, such as extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and the plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene, mcr-1.

Today’s most serious public health threat

Beta-lactam resistance gives bacteria broad resistance to treatment with penicillins and other important antibiotics. As for mcr-1 genes, they protect bacteria against colistin, which is the treatment of last resort for infections caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria. If colistin resistance spreads to bacteria resistant to other antibiotics, those bacteria could cause infections that are truly untreatable, national agencies charged with protecting public health believe.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), antimicrobial resistance is one of the most serious public health threats facing the world today, with 700,000 people dying each year from antimicrobial resistant infections. The O’Neill report, commissioned by the UK government in 2014, estimates that antimicrobial resistant infections could become the leading cause of death worldwide by 2050, causing 10 million deaths a year.

.