A new study conducted on mice paves the way for treatment for people with hemophilia B. A single injection would indeed produce the missing coagulation factor for life.

Affecting approximately 6,000 people in France and 700,000 patients worldwide, hemophilia is a rare abnormality that prevents the blood from clotting, causing a risk of hemorrhage. Carried by a sex chromosome and mainly affecting men, this genetic disease can be particularly painful and cause disabling sequelae, even death if the bleeding is not treated in time.

Hemophilia is caused by a lack or absence of proteins that are usually found in our plasma and that allow the blood to form a clot. They are called coagulation factors. These are factor VIII for hemophilia A and factor IX for hemophilia B (FIX).

Currently, people with hemophilia are treated with injections, usually weekly, containing FIX from animal cells to restore their clotting factors. Expensive and time consuming, these injections can become less and less effective over time.

But that may soon change. Researchers affiliated with the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California have in fact shown in mice that hemophilia B could be treated for life with a single injection. This contains disease-free liver cells capable of producing the missing clotting factor. Published on 1er May in the review Cell Reports, this work could change the lives of people with hemophilia, but also pave the way for similar treatments for related genetic diseases.

Reprogramming cells to produce factor IX

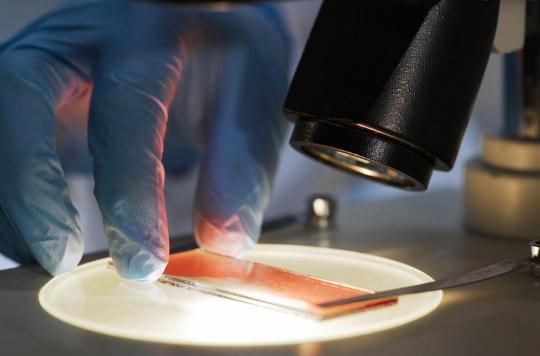

Scientists worked on the transplantation of healthy liver cells, capable of producing FIX, in patients with hemophilia B. They collected blood samples from two human patients with severe hemophilia B, unable to produce coagulation factor IX. They then, in the lab, reprogrammed the cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which have the ability to transform into many other cell types, including those in the liver.

Using CRISPR / Cas9, a tool capable of modifying genes, they then repaired the mutations in each patient’s FIX gene. Finally, they induced these repaired cells to develop into liver precursor cells called hepatocyte cells (HLCs) and transplanted them into mice with hemophilia B.

The researchers then found that these new hepatocyte cells not only made FIX, but that they made enough protein to allow mice to form normal blood clots, and cells to continue to survive – and produce FIX – for at least one year after the transplant.

In people with hemophilia, using their own cells to generate hepatocyte cells, and then transplanting them into their bodies, could help avoid the immune complications that often accompany cell therapy.

However, says Prof. Suvasini Ramaswamy, lead author of the study, more research is needed before conducting clinical trials on human patients. But, she adds, the work already underway demonstrates the value of combining stem cell reprogramming and gene modification in treating genetic diseases.

.