Researchers at the University of East Anglia have just identified a set of genes that promote the spread of bone cancer in patients. This discovery should make it possible to develop gentler treatments, in particular those intended for children.

- By inhibiting the regulator of a potential metastasis factor, researchers from the Universities of East Anglia and Manchester have succeeded in slowing the spread of metastases from primary bone cancer.

- This discovery could eventually lead to a milder treatment than chemotherapy to treat osteosarcoma.

sixth cancer most common in children under 15 With approximately 52,000 new cases recorded each year worldwide, primary bone cancer is a rare but unfortunately often fatal cancer: its five-year survival rate is in fact estimated at 42%.

In question: its tendency to metastasize, in particular to other organs, in particular the lungs. The children who suffer from it must then endure exhausting and painful treatmentsranging from chemotherapy to amputation.

“About a quarter of patients have cancer that has already spread by the time they are diagnosed. About half of patients with seemingly localized disease relapse, with cancer spread being detected later. These numbers have stagnated for more than four decades, with no significant advances in treatment,” said Dr Darrell Green, of Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia.

Identify the factors of development of metastases

Together with Dr Katie Finegan of the University of Manchester, Dr Green is behind a discovery that could revolutionize treatments for children with osteosarcoma, which is the most common type of primary bone cancer. While the genetic factors that cause osteosarcoma are well known (structural variants TP53 and RB1), those favoring its spread to other parts of the body remained unknown until now.

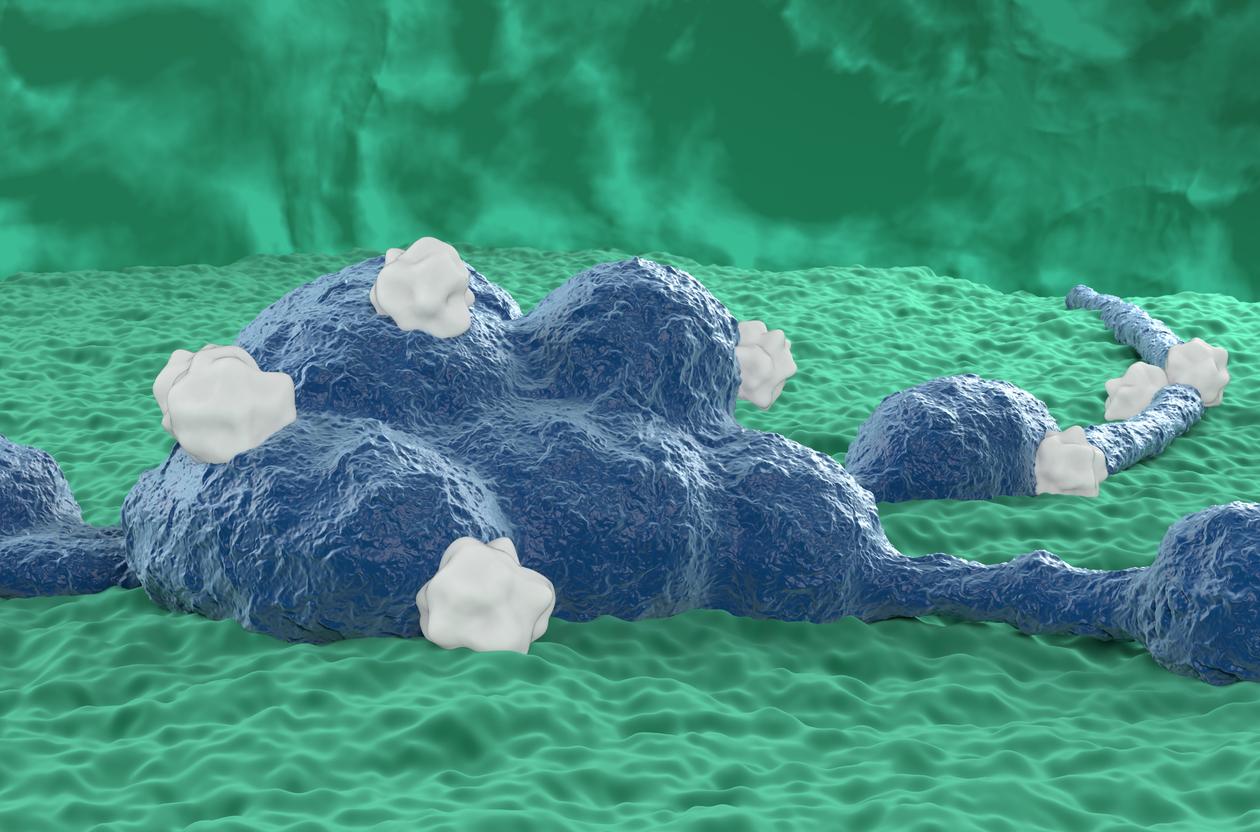

The research team thus succeeded in isolating circulating tumor cells (CTC) and metastatic tumors in the blood of patients. “These cells are essential for scientific study because they efficiently carry out the metastatic process. It was extremely difficult because there is only one such cell per billion normal blood cells – it took more than a year to develop but we cracked it,” says Dr Green.

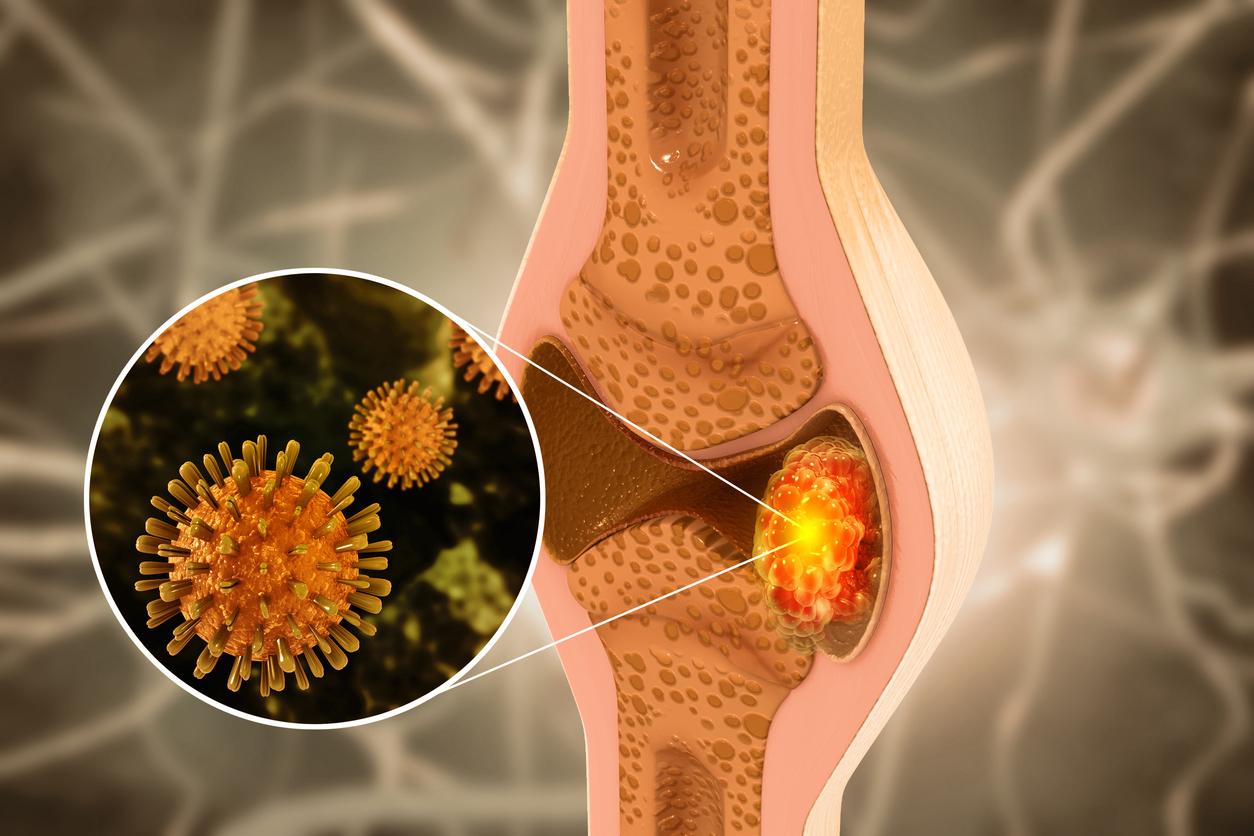

The scientists finally identified a potential factor for metastasis: the MMP9 factor. Well known in the field of cancer, it was previously considered “non-drug” because cancer quickly becomes resistant to treatment or finds a way to escape the target.

Silence the MMP9 regulator

The researchers’ objective was therefore to find the “main regulator” of the MMP9 factor in order to act on it. They then teamed up with scientists at the University of Manchester who were working on the master regulator of MMP9 – MAPK7 – in several cancers using mouse models, including osteosarcoma. Together, they then engineered human osteosarcoma cells to contain a silent version of MAPK7.

They found that when these cells were put into mice, the primary tumor grew much more slowly. More importantly, it did not spread to the lungs, even when the tumors were left to grow for a long time.

“Deeper still, our study shows that silencing MAPK7 halted metastasis because this gene pathway was hijacking a particular part of the immune system that was driving the spread,” says Dr. Green. “It’s really important because not only do we now have a genetic pathway associated with metastasis, but we know that eliminating that genetic pathway actually stops the spread of cancer in a living animal. And we also know how and why. it happens – by hijacking the immune system.”

Now, the next step is to turn this discovery into a treatment. “If these results are effective in clinical trials, it would undoubtedly save lives and improve quality of life, as the treatment should be much gentler, compared to the exhausting chemotherapy and limb amputation that are changing the lives that patients receive today.”

.