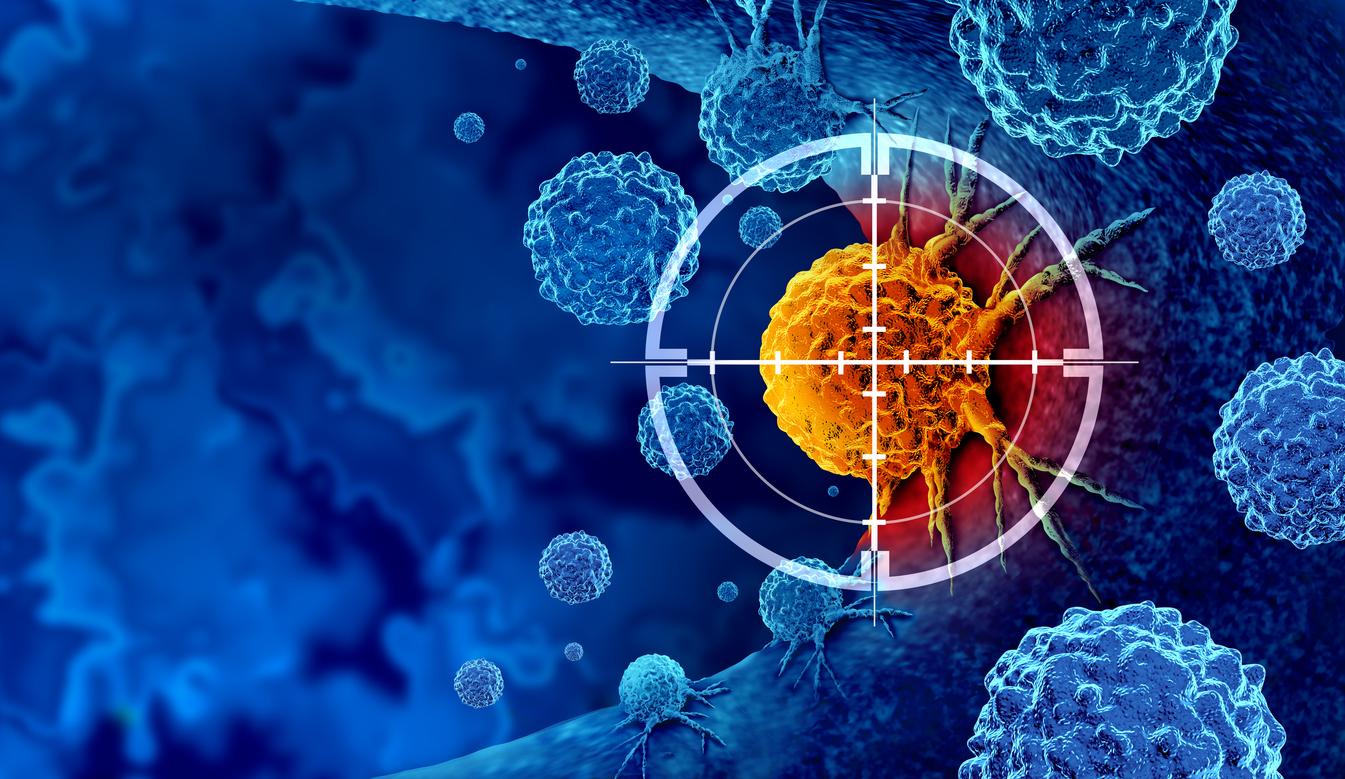

Using ultra-sensitive, high-isolation technology, researchers were able to identify neo-antigens driving anti-tumor responses in a patient.

Being able to identify targets for adoptive immunotherapy is one of the first steps in developing personalized treatment for patients with difficult-to-treat cancers. However, knowing what immune response the patient will have when exposed to a certain type of abnormal protein due to the mutation of a new antigen can be complex.

This is what a team of researchers from UCLA University have managed to do thanks to an ultra-sensitive and high-isolation technology (called imPACT Isolation Technology® by PACT Pharma), designed to isolate neo-epitope T cells. Thanks to this technology, they were able to identify the neo-antigens at the origin of the anti-tumor responses in a patient treated with an anti-PD-1 blockade and thus isolate the responsible T lymphocytes.

The results of this study were presented at a special conference of the American Associate of Cancer Research.

Skin cancer and metastatic melanoma

Using immune blockers to treat people with metastatic melanoma has revolutionized the way this deadly skin cancer was treated. However, many people still cannot benefit from this treatment.

Until now, adoptive immunotherapy, which involves extracting and culturing a patient’s T cells in the laboratory, has targeted shared antigens. This restricted the use of this method for certain patients, in particular because not all cancers can be treated by targeting the same antigen.

The aim of this study and several others is to improve the methods of identifying targets in these therapies in order to develop more personalized treatments.

The researchers analyzed T-cell responses in two patients with advanced melanoma, one who responded well to anti-PD-1 treatment and another who did not.

A better understanding of T cell responses

Using PACT Pharma’s technology, researchers were able to isolate T cells and receptors that recognize tumor mutations. The T-cell receptors were then reintroduced via a non-viral genome to generate T-cell-specific neo-antigens that are used to fight melanoma cells in the patient.

“We hope that a better understanding of the T-cell responses that take place after immune blockade will allow for the establishment of personalized adoptive immunotherapies,” explains Cristina Puig-Saus, lead author of the study.

.