German and Austrian scientists have developed a new therapeutic concept for the treatment of epilepsy.

-1572882643.jpg)

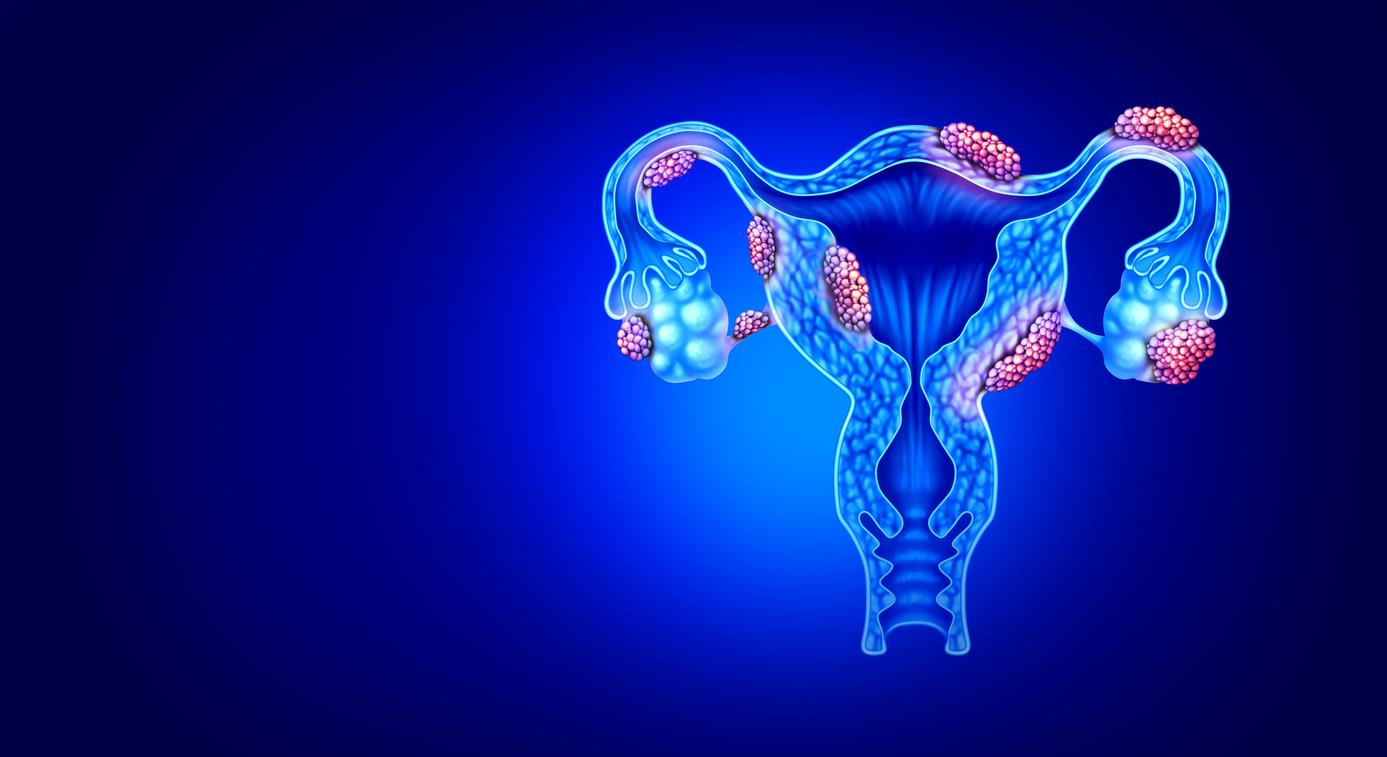

Today, epilepsy affects approximately 5 million people in Europe. This disorder is characterized by recurrent and synchronized discharges of groups of nerve cells. The propagation of these electric shocks interrupts brain functions and causes an epileptic seizure. Its most common form is known as temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) and originates in the sides of the brain. Side effects of ELT can include memory impairment as well as impaired learning and emotional control. Additionally, the quality of life of patients with TLE is severely affected by restrictions placed on their ability to work, drive a car, or play sports.

This is compounded by the fact that the drugs used to treat patients with TLE are often unable to adequately control the disease while still being associated with serious side effects. For this particular group of patients, surgical removal of the temporal lobe often remains the only therapeutic alternative. However, this treatment is associated with adverse cognitive outcomes and does not guarantee that patients will not experience seizures.

To solve this problem, teams of researchers from the medical universities of Berlin (Germany) and Innsbruck (Austria) have developed a new therapeutic concept for the treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy. It is a gene therapy capable of suppressing seizures at their site of origin on demand. It has been shown to be effective in an animal model, and the new method will now be optimized for clinical use. The results of their study were published in the October issue of the journal EMBO Molecular Medicine.

Prevent the spread of the crisis

The new treatment method is based on targeted gene therapy. This technique involves the selective delivery of a specific gene to nerve cells in the region of the brain from which epileptic seizures originate. The gene provides the cells with the information necessary for the synthesis of dynorphins: these are naturally produced peptides that modulate neuronal activity. Once the gene has been introduced into the nerve cells, it remains there permanently. “High-frequency stimulation of nerve cells, such as that seen at the onset of a seizure, results in the release of stored dynorphins. Dynorphin inhibits signal transduction and therefore the epileptic seizure does not spread,” says Professor Christoph Schwarzer from the Department of Pharmacology at the Medical University of Innsbruck.

The neurobiologist and epilepsy specialist adds: “Because cells only release this substance when needed, this type of gene therapy is called ‘release on demand’.” Using an animal model, the researchers were able to demonstrate that this gene therapy is able to suppress epileptic seizures for several months. The researchers did not stop there, and tested their new treatment concept using tissue samples taken from epileptic patients. They successfully demonstrated that dynorphin significantly reduces the severity and frequency of synchronized nerve cell activity in human epileptic tissue.

A rare treatment

As the risk of drug failure of ELT is high, it will be a unique treatment and an innovative answer to the pain of epileptic patients. In addition, the reduction of epileptic seizures is a great achievement, as it also relieved the adverse effects of these seizures on memory and learning. Moreover, no side effects have been observed so far.

If the treatment proves effective, it would offer an alternative to patients for whom ELT drugs fail. “The results of our study are encouraging and give us hope that this new therapeutic concept can also be successful in humans,” said Professor Regine Heilbronn, director of the Institute of Virology at the University of Berlin.

.