One third of people with mental or neurological disorders live in China or India. These countries also offer poor care to their patients.

Mental pathologies are ostracized from society, in some countries more than others. A special series of Lancet Psychiatry looks at the situation in India and China. Together, these countries account for a third of mental, neurological and substance abuse pathologies in the world. And yet, care remains very marginal in the two most populous states on the planet.

Lack of diagnostics

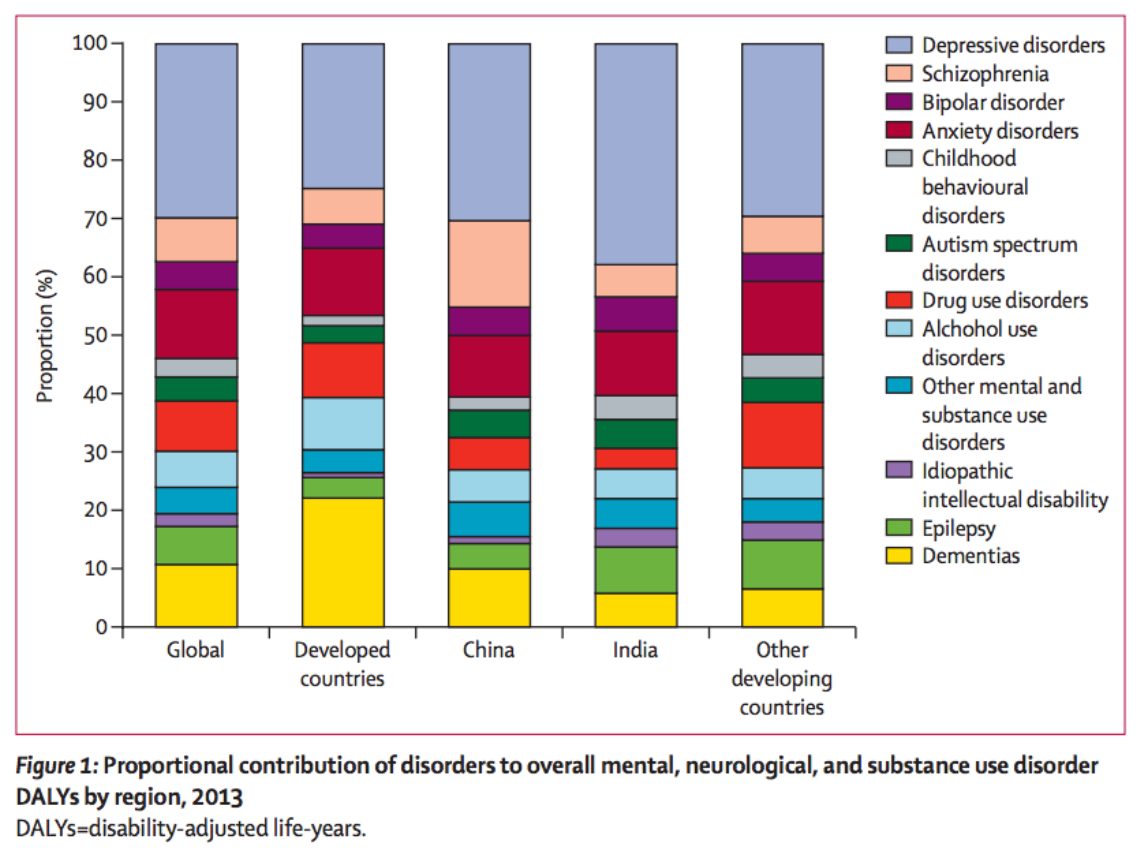

2.5 billion people live in China and India. The burden of mental illness is proportional to this gigantic population: in 2013, the number of years of healthy life lost was estimated at 36 million for China, and 31 million for India. This figure should continue to grow in the years to come.

Substance abuse is by far the most common problem, led by drugs, in these two giant states. But dementia is a growing problem. The expected increase in India is 82%, that in China 56%.

Together, the countries have more mental and neurological pathologies than all the industrialized countries. This does not mean that patients have access to the diagnosis. In fact, only 6% of affected Chinese seek treatment. And 40% of people with psychotic disorders have never seen a health professional. The situation is equally worrying in India: a tenth of patients receive approved treatments.

A progressive policy

Part of the problem lies in the type of medicine available in these countries. Two forms coexist: alternative techniques and traditional approaches. There are many who turn to yoga or faith to alleviate their suffering. More cooperation between sectors should improve access to specialized care, say the authors.

“India has a progressive mental health policy, but the provision of comprehensive services for communities is uneven and the gap in access to treatment is very wide, especially in rural areas,” explains Prof. Vikram Patel of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Political will

The researchers also point to the lack of public sector investment in mental health. In India, less than 1% of the country’s income is injected into this area. This results in poor training of health professionals and unequal access to appropriate services. In China, a law was passed in 2012 and set targets. But the hardest part remains to be done. “The current challenge is to mobilize resources and a lasting political will will be necessary to achieve all the objectives of the law,” insists Prof. Michael Phillips of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. However, it welcomes the efforts made in providing free access to antipsychotic drugs, even if rural areas remain disadvantaged.

.