A study suggests that migraine pain is due to a lack of drainage of the brain’s lymphatic system.

- Migraine is a throbbing, one-sided headache that is disabling.

- Migraine pain is influenced by altered interactions with immune cells and by the fact that calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) prevents cerebrospinal fluid from flowing out of meningeal lymphatic vessels.

- Further research is needed to gain more insight into the links between migraine, CGRP, and meningeal lymphatic vessels.

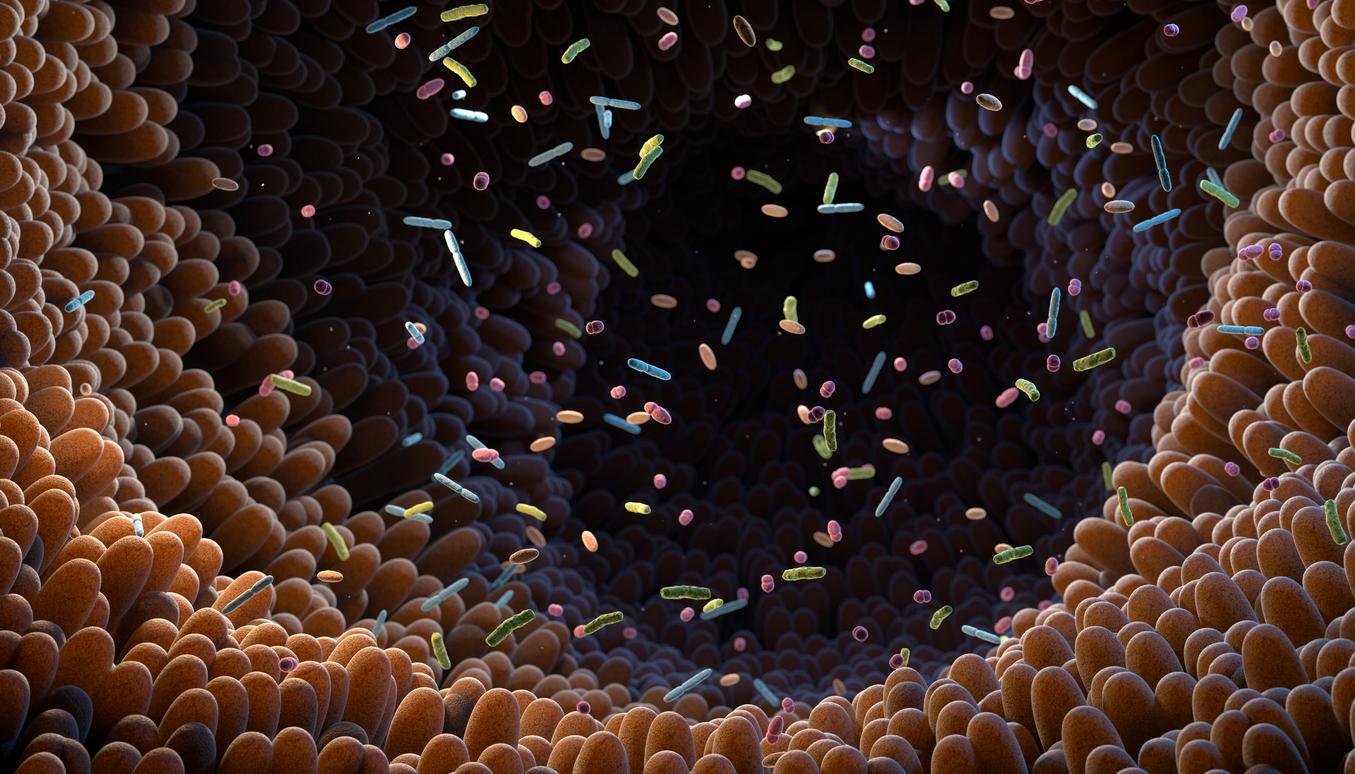

It’s more than just a headache. Migraine sufferers know that this throbbing, one-sided headache is debilitating because it can be very painful. Recently, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (USA) identified how a small protein – called calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) influences the lymphatic vascular system, contributing to pain during migraine attacks. To achieve this discovery, they conducted a study published in the journal Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Migraine: Mice immunized against the effects of CGRP avoided light less

As a reminder, CGRP, which is involved in pain transmission in neurons, is known to be elevated in the meninges, or the layers of tissue surrounding the brain, during migraine attacks. As part of the work, the scientists conducted experiments on mice with lymphatic vasculature deficient for the CGRP receptor and who were being treated for chronic migraine induced by nitroglycerin. They found that rodents immunized against the effects of calcitonin gene-related peptide felt less pain and spent more time in a lighted room compared to those vulnerable to CGRP. “Bright light is a painful stimulus for people with migraine, and the ability to measure similar behaviors in mice validates the translational impact of the study.”

A decrease in the amount of cerebrospinal fluid leaving the skull

Next, using cell culture techniques, the authors assessed how a protein called VE-Cadherin is arranged in the space between individual cells that line lymphatic vessels. It helps keep lymphatic endothelial cells stuck together and controls how much fluid, such as cerebrospinal fluid, can squeeze between lymphatic endothelial cells and leave the vessels.

According to the results, CGRP-treated lymphatic endothelial cells reorganize their VE-Cadherin proteins “so that they are aligned like a zipper on a jacket, in order to maintain a watertight seal. This arrangement prevents fluids from passing between the cells, thus reducing the permeability of these cell layers.” By injecting CGRP and a traceable dye into the meningeal lymphatic vessels, the team observed a significant reduction in the amount of cerebrospinal fluid exiting the skull.

“Our study highlighted the importance of the brain’s lymphatic system in the pathophysiology of migraine pain,” said Kathleen M. Caronco-author of the research. Future studies are needed to gain more information about the links between migraine, CGRP and meningeal lymphatic vessels, the researchers say.