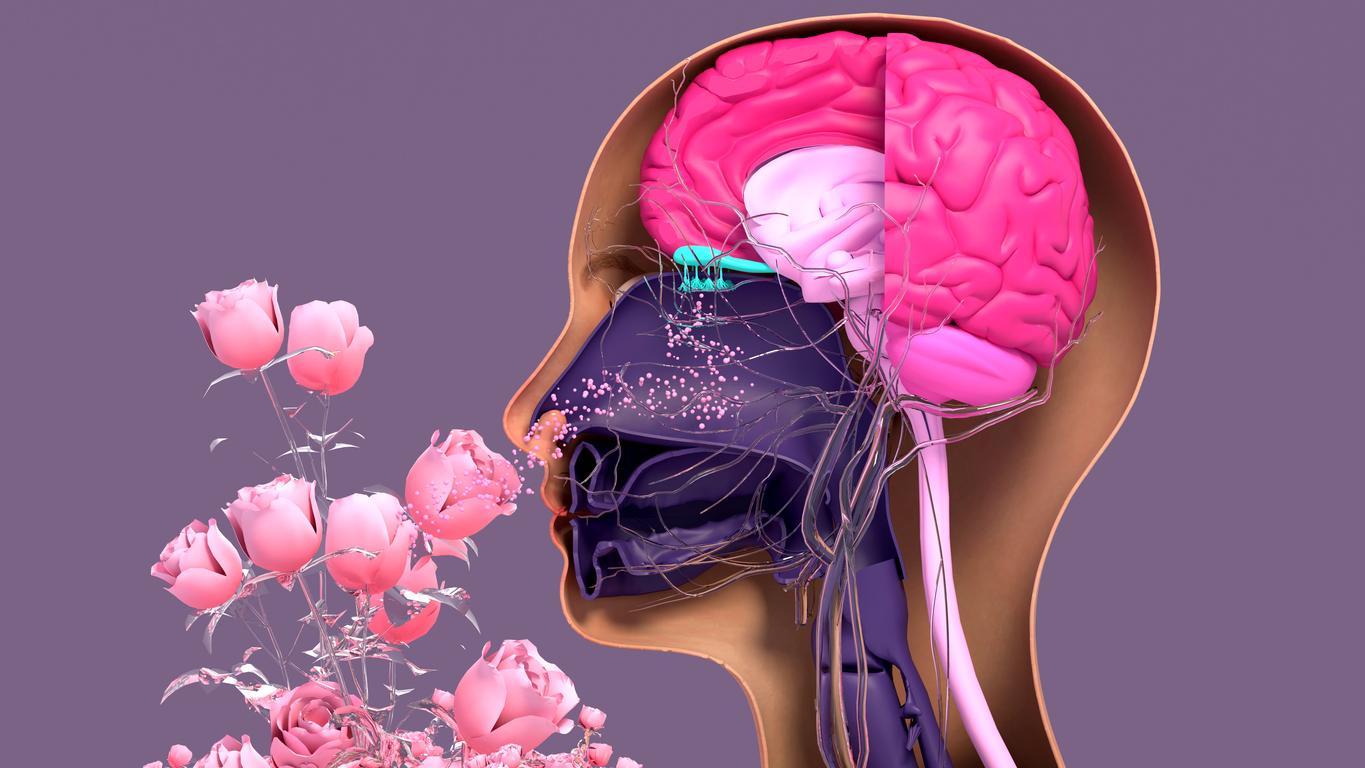

Our sense of smell is, like that of sight, markedly affected by how we process other sensory signals, neuroscience researchers reveal.

- Predictive coding theory maintains that the main function of the brain is to anticipate what is going to happen, so that it can respond adequately to the unexpected. Most research on the subject has been confined to the sense of sight, scientists have looked at the sense of smell to find out if it works in the same way.

- According to their study, “smell is strongly influenced by signals from the other senses, while the senses of sight and hearing are affected to a much lesser extent.”

- “Smell depends much more on predictions than vision […] When the brain tries to identify odors that it did not expect, both the olfactory brain and the visual brain are activated, despite the absence of visual cues in the task.”

A famous theory in neuroscience, predictive coding maintains that the main function of the brain is to anticipate what will happen, in order to be able to react adequately to the unexpected. Most research on the subject has focused on the sense of sight, what we see to predict what will happen next.

Scientists at Stockholm University in Sweden looked at other senses to find out if any of them work in the same way. And, as they predicted, smell is strongly linked to how we process other sensory signals.

The sense of smell relies heavily on predictions

As part of their work, published in The Journal of Neuroscience, the researchers conducted three separate experiments, two behavioral and one using the functional MRI method to observe brain activity, on nearly 120 healthy participants. On multiple occasions, they presented them with different familiar stimuli (lemon, lavender, pear, lilac) in the form of odors, images or spoken words, and the volunteers had to quickly decide whether one sensory stimulus corresponded to another. For example, after hearing the word lemon and then smelling an odor or seeing an image, they had to say whether it corresponded or not. The objective was to assess the time taken by participants to decide.

“Overall, the sights and smells expected led to faster decisions, which fits well with the theory of predictive coding”explain the researchers in a communicated. To compare the senses with each other, they then looked at differences in response speeds, “a greater delay for the stimuli unexpected meant[ant] that “meaning relies more on predictions”. They found that “smell is strongly influenced by signals from the other senses, while the sense of sight and hearing are affected to a much lesser extent.”

Smell strongly influenced by signals from other senses

The results of the study show that “smell depended much more on predictions than vision.” The proof, “When the brain tries to identify odors that it did not expect, the olfactory brain and the visual brain are activated, despite the absence of visual cues in the task.”

In other words, the olfactory brain has a way “completely unique” to process odors to know if they are expected or not. The sense of smell alerts us to odors we did not expect, and engages the visual brain, to be able to see the origin of the odor. “It’s a smart feature of us humans, who are particularly bad at recognizing smells if we don’t have cues.”conclude the authors of the study.