Already singled out by the scientific community for their harmfulness to our physical health, food additives are also responsible for behavioral disorders.

From prepared meals to industrial pastries, via mass-market charcuterie and confectionery: food additives are present in the majority of processed foods that we consume every day.

Used by manufacturers to enhance the taste of food, to make it more attractive or to increase its shelf life, these food additives are not harmless. For several years, the scientific community has been concerned about the consequences of these famous “E”s on our health. Accused in particular of being carcinogenic, of disrupting our immune system or of being the cause of chronic pain, food additives are not without risk for our mental health either.

In an article published this month in the journal Scientific Reportsneuroscientists from Georgia State University, in the United States, establish a link between two additives frequently used in the food industry and the onset of anxiety behavior disorders.

A mysterious link between gut and brain

The authors of the study were interested in two additives: polysorbate 80 (E433) and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (E466), two emulsifiers and gelling agents regularly added to the preparations of biscuits, cakes, breads and in margarine to improve their texture and extend their shelf life.

“We asked ourselves the following question: can the effects of emulsifiers on general systemic inflammation also be extended to the brain and behavior?”, explains in a press release Geert de Vries, professor of neurosciences at Georgia State University and lead author of the study. “The answer is yes.”

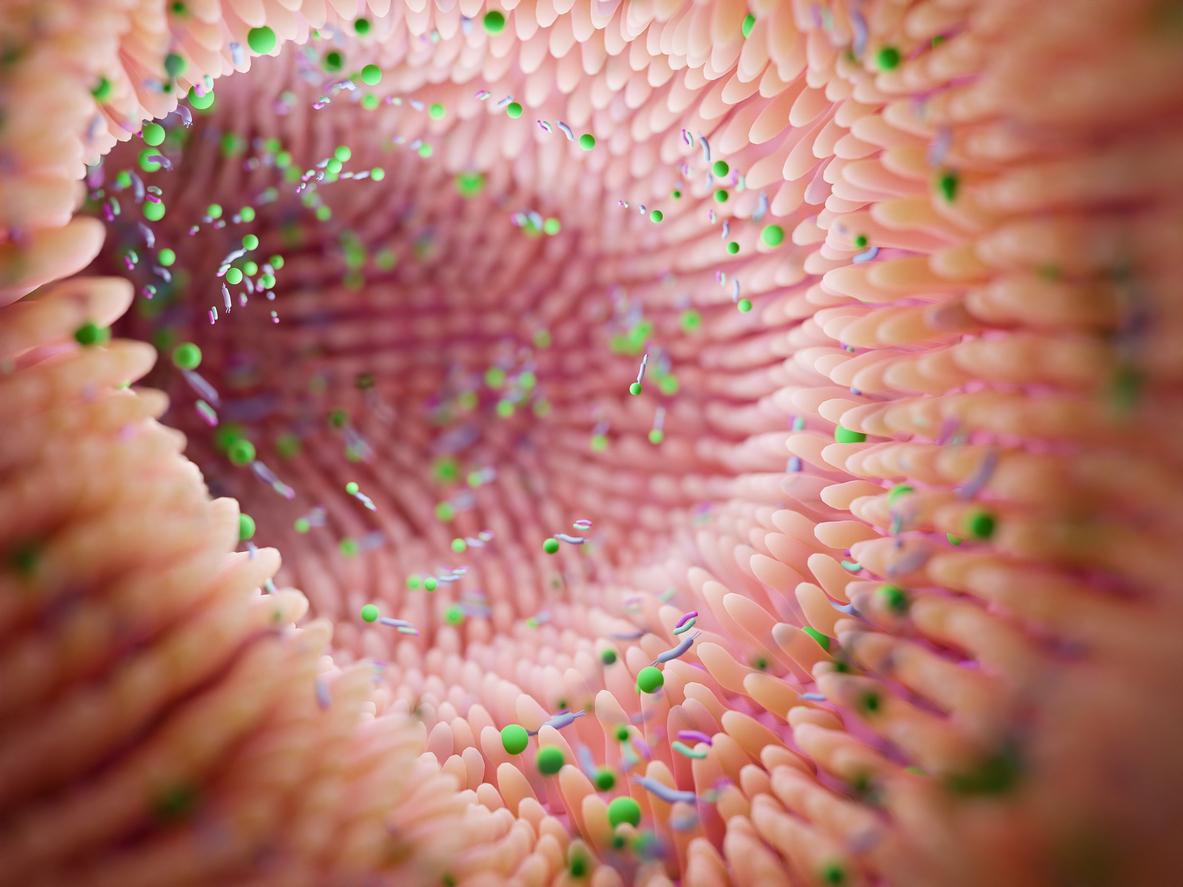

In previous work, the same team of neuroscientists had already taken an interest in these two controversial additives and had discovered that they could cause mild inflammation in the intestines of mice by modifying their intestinal microbiota, i.e. the billions of micro-organisms (bacteria, archaea, fungi) living in the intestinal tract.

This time they sought to understand, still on a mouse model, what could be the impact of these two emulsifiers on behavior. Indeed, the scientific community has already established that there is a link between the intestinal microbiota and the central nervous system. The intestines themselves have their own nervous system: called the enteric nervous system, it has more than 500 million neurons. It is these nerve cells that communicate with neurons in the brain through what researchers call the gut-brain axis. According to them, this axis could be the key to understanding how certain food additives affect behavior.

A gendered modification of behavior

“We know that inflammation causes local immune cells to produce signaling molecules that can affect tissues in other places, including the brain,” explains Prof. de Vries. “The gut also contains branches of the vagus nerve, which forms a direct information pathway to the brain.”

To confirm or refute their theory, the neuroscientists analyzed the effect of the additives E433 and E466 on the microbiota and the behavior of mice by giving them via drinking water. After 12 weeks, they found that both male and female mice showed a change in behavior. But, curiously, the emulsifiers seemed to affect them differently: while the male mice had a behavior close to anxiety, the behavior of the females was closer to a reduction in social behavior. This could be explained by the differences between the immune system and the composition of the intestinal microbiota according to gender, the researchers suggest.

Although the results are based on a mouse model, the study authors argue that their finding can certainly be applied to humans and even be used to explain the onset of behavioral disorders. However, further research is needed, in particular to better understand the link between intestinal flora and the human brain. “We are currently studying the mechanisms by which food emulsifiers influence the intestinal microbiota, as well as the relevance of these results for humans”, Benoît Chassaing, assistant professor of neuroscience and co-author of the study.