While everyone is wondering about genome editing, Crispr has enabled the development of a new ultra-sensitive and rapid genetic detection test.

In a few years, Crispr-Cas9 has become the darling of the media. “Molecular scissors,” as they were quickly nicknamed, offer breathtaking perspectives in the field of genome engineering. In a (relatively) simple and inexpensive way, it becomes possible to modify a precise sequence of DNA, opening the door to new gene therapies and to the modification of the genome.

The general states of bioethics, which are taking place at the moment, will no doubt not escape Crispr. It must be said that the questions opened by genome editing are unfathomable: whether it is research on human embryos (this is the case in China and the United States), the modification of fauna (mosquitoes malaria resistant) or transhumanist folklore which begins to take shape (with the “biohacker” Josiah Zayner, for example).

Elementary, my dear Crispr

What to forget that Crispr is not only a tool of modification of the genome: in a more prosaic way, and undoubtedly much more useful in the short term, this molecular system resulting from bacteria also makes it possible to make genetic diagnosis with a sensitivity and ease of use hitherto unthinkable.

Baptized Sherlock (Specific High Sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter Unlocking), the device was unveiled last spring by a team from the Broad Institute, which brings together MIT and Harvard. Thanks to him, researchers were able to identify the Zika and Dengue viruses in saliva and urine, or even detect carcinogenic mutations in blood samples.

An ultra-sensitive test

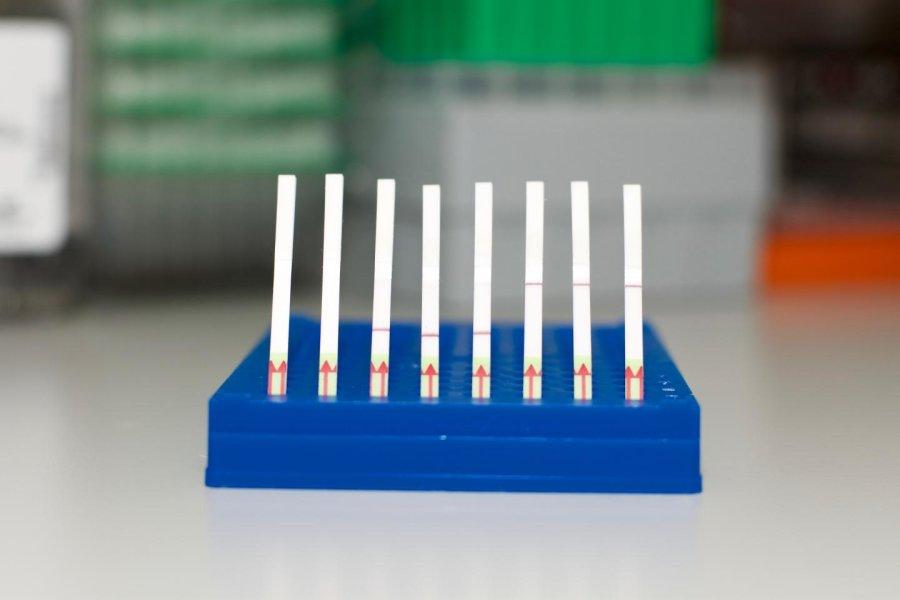

Exposed in Science recently, the latest version of the device comes in the form of simple strips of paper, like a pH test. Except that they allow the detection of any pre-established genetic sequence, practically without any manipulation.

Zhang lab, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, all rights reserved.

To do this, the device is not based on Crispr-Cas9 but on a cousin protein: Crispr-Cas13. Like its close cousin for DNA, it can detect very precise RNA sequences.

But unlike “molecular scissors”, the Cas13 enzyme does not cut corners: once the target is detected, it sets out to cut out all the surrounding RNA. A collateral activity used by researchers to amplify the initial signal, and to be able to detect infinitesimal quantities of genetic material.

For less than a dollar

Sherlock is thus able to detect very low viral loads and point mutations: he is approximately a million times more sensitive than the Elisa immunological method commonly used to detect the presence of antibodies or antigens, for example in pregnancy or HIV tests. All in less than an hour and for a sum that promises to be very low: less than $ 1, according to the members of the research team.

It would thus be possible to detect new epidemics very easily in developing countries, to generalize liquid biopsies or even to detect antimicrobial resistance genes in bacteria. A revolution perhaps less dizzying than the famous “molecular scissors, but with incomparable applications. The Broad Institute, which has the license, did not hide its desire to offer its test very quickly on the market.

.