Using human stem cells, researchers have succeeded in recreating a functional intestine in the laboratory. Thanks to this model, they were able to study a rare disease.

For the first time, American researchers from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and a French team from Inserm have succeeded in recreating a functional human intestine in the laboratory. This medical feat, presented in Nature Medicine, was carried out using human stem cells cultured in the laboratory. Until then, there was no biological model that would allow us to study this organ in the laboratory, presented as “the second brain”.

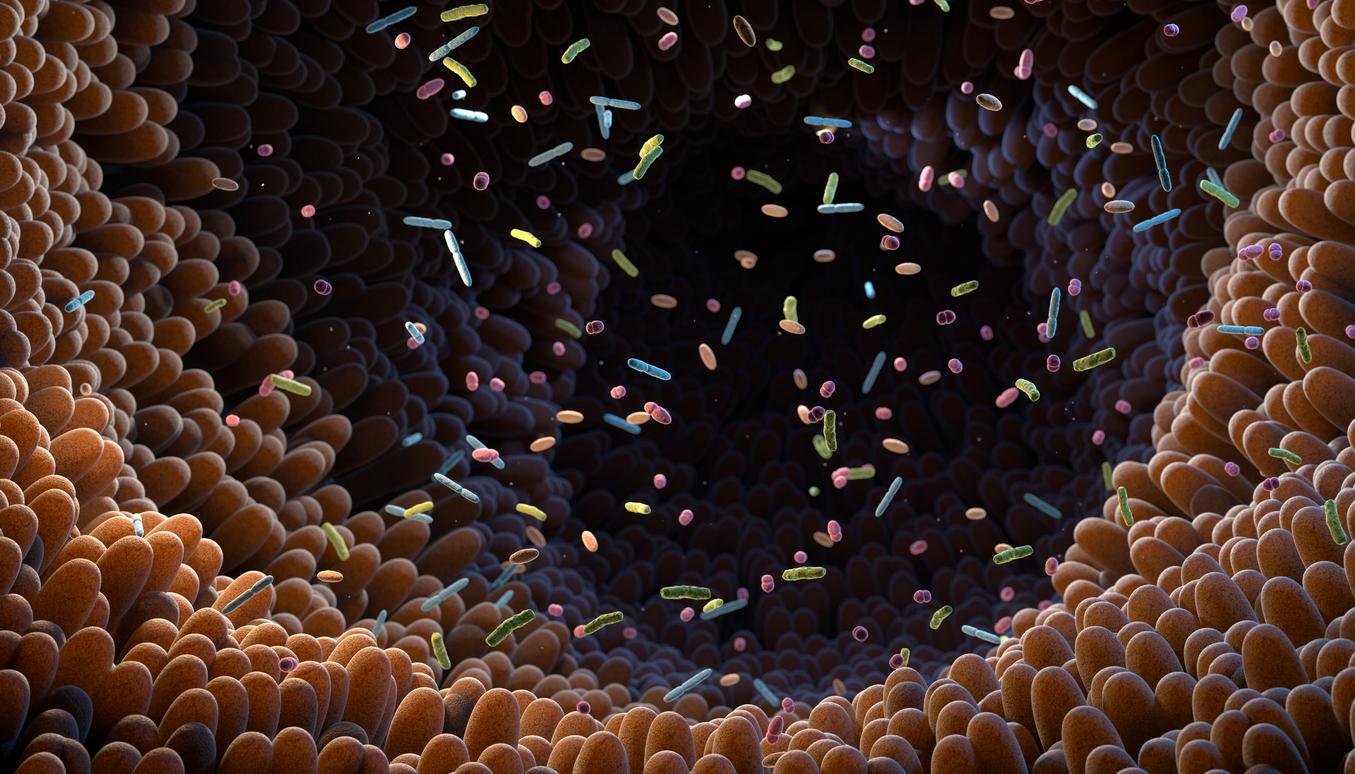

The intestine is indeed an essential organ in the body. It has its own nervous system which controls the contraction of the intestinal muscles. It is thus responsible for digestion, the production of certain hormones as well as the permeability of the walls of the intestine. Consequently, the dysfunctions of these neurons generate numerous pathologies, sometimes severe.

Recreating this set in the laboratory had until now been very complicated. To overcome technical obstacles, the Franco-American team has developed an innovative technique using pluripotent human stem cells. These can differentiate into any specialized cells such as skin, liver or kidney cells.

Functional mini-intestines

To make the cells become intestinal cells, the researchers added different cocktails of molecules to the Petri dishes. But with this approach, the nervous system of the intestine did not develop. At the same time, they therefore had to create nerve cells at the embryonic stage called neural crest cells, and manipulate them so that they become nerve cells in the intestine.

“The difficulty of this step was to identify how and when to incorporate the cells of the neural crest in the developing intestine previously created in vitro”, explains Maxime Mahé, researcher at Inserm, co-first author of this article. job.

These two tissues were then placed together in a culture dish. Result: the whole created an intestinal tissue similar to the fetal intestine. At the end of its development, “mini-intestines”, called intestinal organoids, emerged.

The next challenge for the researchers was to ensure that these organoids were functional. He then implanted them in mice lacking an immune system in order to avoid anti-rejection phenomena. Thanks to this transplant, the team was able to observe the development in vivo those mini-intestines which assembled “in a remarkably similar fashion” to the human gut and performed physiological functions.

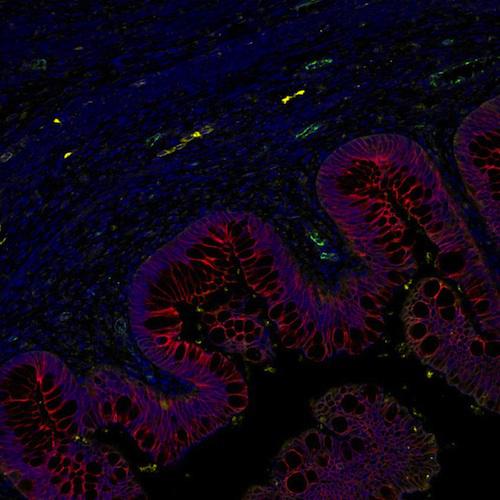

Source: Inserm. Cross section of human intestinal organoid possessing an enteric nervous system after transplantation in mice. We visualize the intestinal epithelium in red open on a lumen. The tissue underlying the epithelium is rich in blood vessels (green, CD31) and features neurons (yellow, TUBB3) also derived from human pluripotent stem cells. The tissue observed is incredibly similar to normal human tissue.

Studying intestinal diseases

With this validated laboratory model, scientists were able to study a rare bowel disease, Hirschsprung’s disease. People with this pathology suffer from constipation and intestinal obstruction because the intestinal nervous system has not formed. This disease can also be fatal in patients with a mutation in the PHOX2B gene. A deleterious effect demonstrated in vitro and in mice.

“Our work marks an essential step in the understanding of digestive diseases in humans where few models are present. This new technology offers a “screening” platform for new intestinal therapies. These are still the beginnings but a perspective of regenerative and personalized medicine is possible, in particular with a view to the transplantation of a specific intestine for each patient ”, rejoices Maxime Mahé.

.